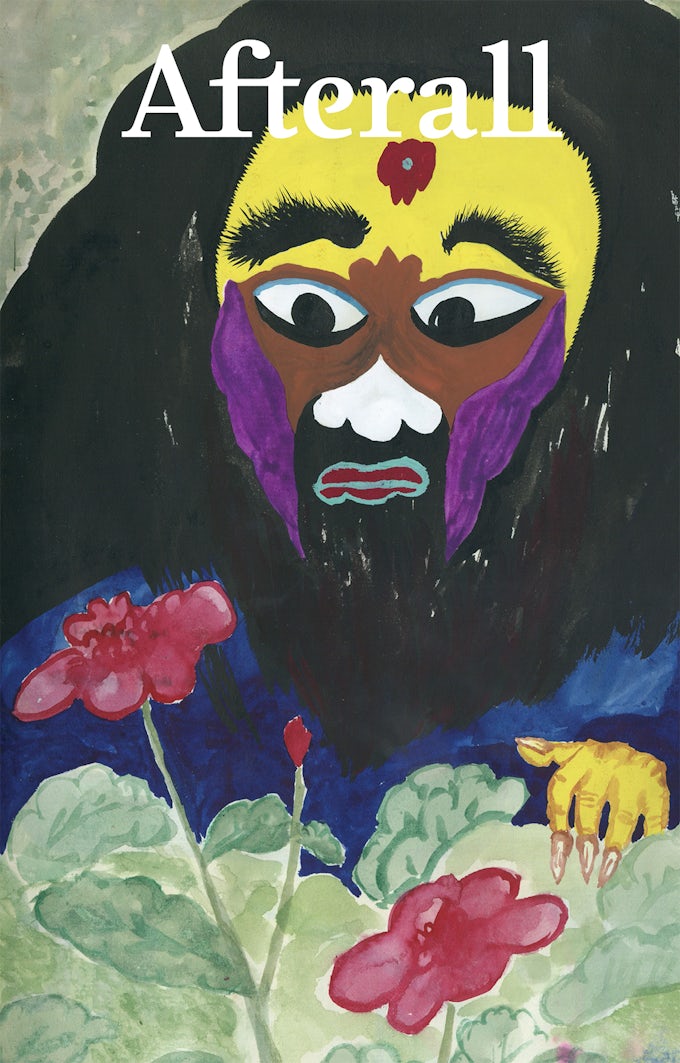

Issue 46

Autumn/Winter 2018

Editors: Ana Bilbao, Charles Esche, Anders Kreuger, Ute Meta Bauer, David Morris, Anca Rujoiu, Charles Stankieveh.

Founding editors: Charles Esche, Mark Lewis.

Table of contents

Foreword

Contextual Essays

- Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? Premises for Burmese Contemporary Art with Po Po, Tun Win Aung, Wah Nu and Min Thein Sung – Yin Ker

- Cultural Marxists Like Us – Sven Lütticken

- Beyond Essentialism: Contemporary Moana Art from Aotearoa New Zealand – Lana Lopesi

Artists

Lee Wen

- Lee Wen: Performing Yellow – Alice Ming Wai Jim

- Line Form Colour Action – Võ Hồng Chương-Đài

- Mujeres Creando insert: La creatividad es un instrumento de lucha y el cambio social un hecho creativo (Creativity Is an Instrument of Struggle, and Social Change a Creative Act)

Mujeres Creando

- To the Last Consequences: Mujeres Creando in Conversation with Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz and Pablo Lafuente – Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz & Pablo Lafuente

Chto Delat

- The End of the Line: Historicity, Possibility and Perestroika – Simon Sheikh

- The Grammar of Collectivity as Experimented by Chto Delat – Irmgard Emmelhainz

Kader Attia

- Kader Attia: Voices of Resistance – Giovanna Zapperi

- Time Torn – Hannah Gregory

Events, Works, Exhibitions

- The Art World Has Lost Its Mind: Lorraine O’Grady and the Birth of Mlle Bourgeoise Noire – Bridget R. Cooks

- Recasting History: The Transformative Cinema of Steve McQueen and Raoul Peck – Karen Alexander

Foreword

Written by Anca Rujoiu

‘History is not the past, it is the present’, states James Baldwin in Raoul Peck’s poignant documentary I Am Not Your Negro(2016). Quoted in the comparative essay by Karen Alexander that draws parallels between two film-makers of different generations, Peck (Haiti) and Steve McQueen (UK), Baldwin’s words capture the core of this Afterall issue. Conceived in Singapore – collectively by the editorial team – and traversing different geographies and contexts, from Southeast Asia to The Americas, this issue is a tour de force into artistic practices taking a clear position against the long-lasting endurance of oppressive systems, be it racial, patriarchal or colonial.

It is little known that the invention of race goes back to the age of Enlightenment, in particular to the work of botanist and naturalist Carl Linneaus who marked race as a classificatory tool of biological difference across humankind. Loaded with social prejudices since its formulation, the idea of race served colonial exploitations while validating European superiority. In 1992, during his time in London, the Singaporean artist Lee Wen started his iconic work, the performance series Journey of the Yellow Man, an exploration of identity and representation. The Yellow Man, as Alice Ming Wai Jim suggests, performs the explicit. He performs the racialisation of labour, harking back to the colonial figure of the coolie up to the present-day migrant worker subjected to labour coercion and anti-foreigner sentiments. He performs the racialisation of the body within a global discourse – including modern-day Orientalism – through the multitude of connotations ascribed to yellow in different contexts where the Yellow Man journeyed. From the exterior space of performance art, Võ H`ong Chu’o’ng-Đai turns attention to the interior space of notebooks and sketchbooks as traces of Lee Wen’s performative practice. It is in his drawings and studies that Lee Wen’s colour-based expression of the body at the intersection between the natural and social landscape first emerges. Within the legacy of colonial violence, the French-Algerian artist Kader Attia explores the practice of repair as a form of healing the racialised subject. Giovanna Zapperi analyses such practices in several works by the artist as well in the activity of his independent art space, La Colonie, established in 2015 in Paris in the midst of increasing racism and Islamophobia. As Hannah Gregory explains, for Attia the methodology of repair informed by Asian and African practices, implies the visibility, the exposure of the gesture giving the damaged object or the injured body a new life rather than a return to the original state.

A form of revision in the practice of the Russian collective Chto Delat (What is to be done?) is analysed by Simon Sheikh through Perestroika Timeline (2009), a work that thematically and conceptually addresses the possibilities of reconstruction, the original meaning in Russian of this reform movement that marked the Soviet Union’s last decade. A trope of historicisation in contemporary art, the timeline became a tool for writing alternative histories and representing suppressed narratives. As with Group Material’s timelines based on a heterogenous collection of events, Chto Delat mixes registers and references while distinctively introducing a speculative approach to history. Asking what could have happened in the post-communist space rather than what has happened, the hurried embrace of neoliberal order, is an exercise of reimagining the future as a question, to which as Sheikh concludes, there cannot be an answer. Chto Delat works within the ethos of perestroika as a concept of reform of socialist politics, argues Irmgard Emmelhainz, who explores how collectivity is not only an organising principle of their practice, but also a form of artistic experimentation. While addressing Chto Delat’s engagement with the Zapatista radical movement in Mexico, Emmelhainz underscores what has been overlooked in this context: collectivity, as a form of political resistance, is an expression of decolonisation.

Purchase

The publication is available for purchase. If you would like specific articles only, it is also available individually and to be downloaded as PDFs.

Purchase full publication

Buy via University of Chicago Press

Buy via Central Books

Purchase individual articles

Buy via University of Chicago Press