Anahita Delcorde: As a writer in residence at Afterall, I first wanted to ask you about the role that writing plays in your visual practice. You have a background in comparative literature, you screen write for television, and have yourself been a writer in residence at the Whitechapel Gallery. You have also published your memoirs (The Girl Who Fell to Earth. A Memoir, 2012), and have edited Fresh Hell (2015), the 8th issue of the art writing journal The Happy Hypocrite. How does writing inform your visual work, and how do visuals influence your writing?

Sophia Al-Maria: I was just thinking about this recently. Have you ever heard about the medieval Arabic doctrine known as the Science of letters (al-ilm al-huruf) by the mystic, scholar and poet Ibn’Arabi? It’s a sort of esoteric, cult book, about how letters of the alphabet have powers or meanings which are related to the stars. It really struck me when I learned about it, because at the beginning of the verses of the Qur’an, there are these individual letters that are just there and which are the subject of much debate. But also, when I was writing The Girl Who Fell To Earth, I had this urge to categorise my chapter headings with star constellations. Like types of ‘beats’ in a life that had been pulled out to illustrate a more general story, that hopefully people would relate to. I have this cosmic feeling between writing, mapping stars, visuals, pattern recognition, repetitions. Everything starts with a seed and in writing, it’s a letter.

Maybe because of Covid and of being stuck in a room for a long time, I’ve become suspicious of only using language and not the body, or embodiment, in a way that I hadn’t been before. I am feeling very averse to the ways in which there is this mass encouragement to simply move online and out of your physical surroundings. And writing, whether in code, on social media, in your news – fake and otherwise – is all part of that, which feels very slippery to me. Basically, I’m granny.

AD: This reminds me of t araxos (2021–22), an installation which is currently on view outside the Serpentine Galleries. This public sculpture was also the space for a performance, tarax’up, which was conceived as a time to slow down and embrace silence. Which is interesting, as it is right next to the Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park. Did that come into play when thinking about the project?

SAM: It definitely did, although not so much in the sense that writing was a suspicious thing to me. Or that words are magic. You can use them in all kinds of way: to seduce someone, to heal someone, but also to start or end a war.

There’s a sort of mythology around t araxos, which was developed over the course of the years that I’ve been working on it, and there will be a book about it eventually. I think of the work very much as a portal to the self, through meditation, time, and slowness. Over two years ago, I had already invited Tosh Basco [also known as Boychild] to inaugurate the piece, almost like a La Jetée science-fiction figure that would just appear in the park. When t araxos opened, she performed for twelve hours in all weather, which was intense. It culminated in an hour with Kelsey Lu and I. Kelsey Lu played the theremin and cello and sang, and I read the poems that I had composed on the spot. The poems were observations of things that had been going on in the day, during those twelve hours: the names of dogs that were running by that people were shouting after, like Luna and Leo…

AD: We also hear you speak and perform in many of your videos. In Tender Point Ruin (2021),you share childhood memories of games you played, you show your text messages on screen. We also see you get a tattoo in Beast Type Song (2019) – your work is very intimate. How did your own physical and aural presence come into being in your videos? And how important is that to you?

SAM: Well, you’re also a writer. I don’t know if you write because you experience some kind of shyness, but that’s definitely something that was a reason for why I wrote for so long. I didn’t appear in my films; my voice wasn’t in them. I was hiding in a way. There’s this quote by Michel Foucault which I remember writing down somewhere; ‘I am no doubt not the only one who writes in order to have no face.’ 01 I think this was fundamental for me for a long time. Also, quite frankly, being uncertain about being photographed publicly or being visible in my own works, stemmed from being from Qatar and not wanting to hurt my family in any way. And so, to tread quite lightly. It was only after many years of being away, of getting old enough to no longer be a viable marriage option, and of coming out, that I felt comfortable for the first time to be on camera for Beast Type Song. I think I had become angry enough. The work was one of those stories that I didn’t feel like anyone else could do. So yes, the intimacy element is very important to me, as my route to direct connections with audiences is to be vulnerable and honest. I suppose that sort of folded itself over into the art.

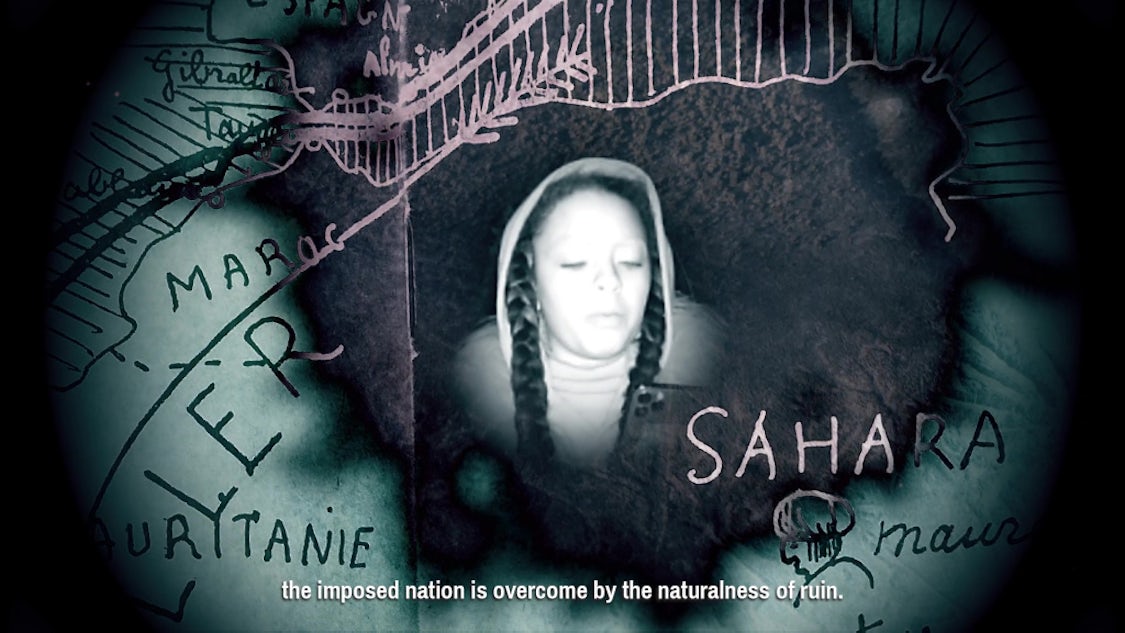

AD: Beast Type Song is a multi-layered piece which addresses different ways of communicating and building intimacy, as it interweaves several histories of colonialism, in a variety of languages, and with dance. The work also takes its roots in The Arab Apocalypse (1989) by Etel Adnan, a poem which presents the sun as a metaphor for colonial rule. The poem is visually and literary quite unique as it incorporates drawings amidst verses and unknown typefaces. It explores different ways of thinking about language. This refers back to what you previously said regarding performance, and non-linguistic ways of sharing… For Beast Type Song, how did dance emerge in relation to telling those stories?

SAM: You picked up on a lower layer that has been running through my work for a couple of years now, which is language versus embodiment, being in one’s body, and using your body for communication. It’s about being sensitive to the things that we can’t see or hear, touch, smell or feel, and necessarily about trying to reach those places. Beast Type Song is a collaboration and a dance on many levels: Tosh Basco is dancing with a drone, Yumna Marual is also performing with a Steadicam operator, which is very much a dance. Shortly before that, I had also shot something which I still haven’t completed with a CNN finance reporter. Being in the New York Stock Exchange and watching those cameras move with the anchors was really fascinating because it was like a waltz, a mating dance, very much like the hunter and the hunted. The relationship between the camera, its subject and our own gaze as viewers, strongly underscores a lot of my work.

AD: Can the exhibition space intervene in these dynamics? Do you think of the exhibition space as another medium of communication, which can maybe be a place for questioning power structures that are present in storytelling or ways of talking about history? I’m thinking about this especially since you are currently preparing an exhibition at Project Native Informant. 02

SAM: I feel that I have been film-focused, and so my installations have remained pretty simple. However, I have a few things coming up that are a lot more complex in relation to space. Maybe because of this body thing, it’s not just about telling a story on a screen. Rather, there’s this yearning to connect. I think I still want to try to do things that are extremely simple, but are still interventions in the way you experience something. What I’m working on now for the gallery is very much like palimpsest-layer-collage-garbage work.

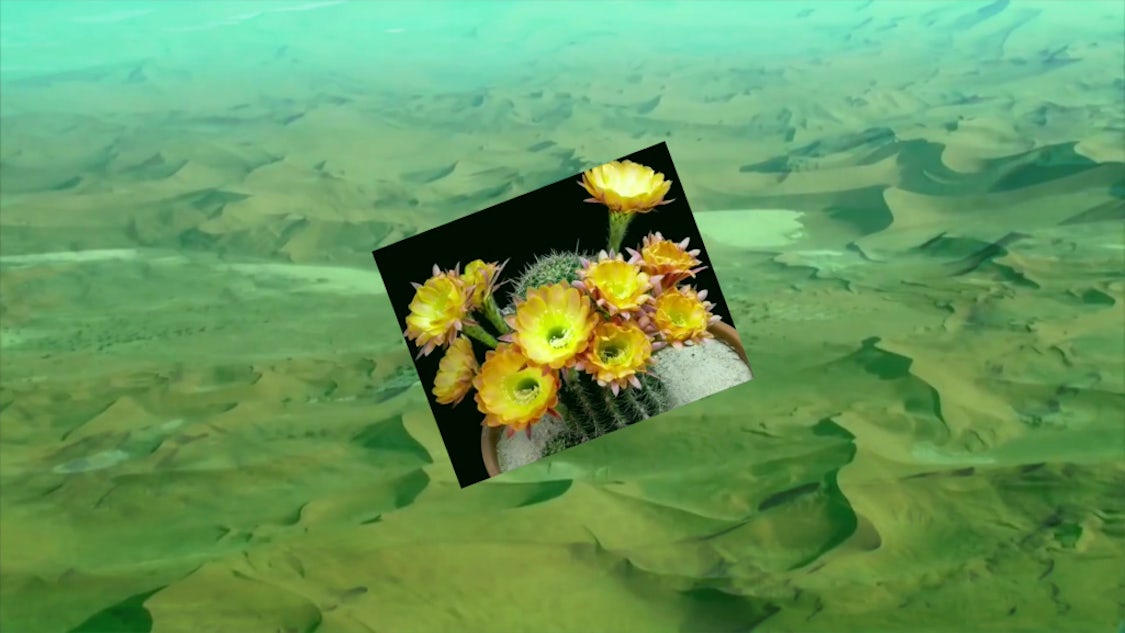

AD: Collage feels very central to the way you edit your videos, such as in The Future Was Desert (Part I & II) (2016),whichsuperposes YouTube footage with your own. The montage of your video works is never linear and is always layered. Is there a particular way you add or edit elements? How do you know when to stop?

SAM: It usually happens when I’ve taken a break and come back to it. I have this vivid memory of drawing a picture when I was a kid and of my mom telling me I was going to ruin it if I kept on drawing. I think about that often because I do have this desire to be quite maximalist. I also think there’s something in the process that has to happen almost without me. Sometimes, it just has to sit. I need to not look at it for a week, even though I don’t always have that luxury – in fact most of the time. For me, a big part of knowing when to stop is noticing that it’s almost alien to me now, as if it has a life of its own. For example, a lot of the time I don’t remember what’s in the books I wrote. I’ve had to look through a lot of archive crap of mine from the past twenty years. And it’s insane how I’m reading things I wrote, journals or lists, and have no recollection of them. But often, that’s the only way that you know it’s good. Because I literally don’t associate it with myself anymore.

AD: It’s great that you mention things taking a life of their own. I was thinking about this regarding the notion of Gulf Futurism which you coined approximately ten years ago, and which you have since revisited and pluralised as Gulf Futurisms in your recent collection of essays Sad Sacks (2019).03 I’m interested in how definitions of concepts can evolve over time and wanted to ask you about your own relationship to this notion that you’ve written about previously.

SAM: I recognised a bit too late the way in which it was a very easily commodifiable, sexy term that was being used by nerdy white bros. To be fair, I am steeped deeply in the same kind of sci-fi literature that the nerdy white bros that I’m talking about read, but I think that’s an example of something that wasn’t ready to be public yet. Like an uncooked, unfinished, still-too-close-to-me kind of work. But the interesting thing is that lately I’ve been revising it. Again, I think it’s a right. It’s very important for me to always have the right to change something that I’ve written, to redact, to have annotations, to write in the margins.

AD: I guess that’s the beauty of the * (asterisk), as a singular element of language that allows layering thoughts, and which you refer to visually in many of your works, such as Beast Type Song or t araxos.

SAM: Exactly. That’s why the asterisk is so important. The history of it as a symbol is really fascinating.

AD: It’s also an interesting answer to traditional ideas of failure, as it offers space for rethinking, building over, but not erasing. A few of your works actually look into the idea of ruins, abandoned projects, projects that you haven’t finished or that were not made possible because of external factors. For example, Virgin with a Memory (2014) is based on the unfinished film project Berretta. Beast Type Song is shot in the former, dilapidated, and empty Holborn building of Central Saint Martins. Can you tell me more about your exploration of ruins?

SAM: Oh, the ruins, Al-Atlal (1952)… 04 There’s a part in Tender Point Ruin where Etel Adnan reads aloud a definition of Al-Atlal over a shot of the moon. It was a real blessing to get Etel’s voice into the video, because her work has been so important to me. The ‘ruin’ has always fascinated me since I found out, during a semester studying pre-Islamic literature, that it was part of a poetic format. It was like a revelation, because I linked it to my own writings and even the flickers of art that I was doing back then. I remember one of my first art projects was a comic book strip which I did with two other comic book writers, and we conceived this big apocalyptic mural and had our characters interact with each other at random. My character was like a river rat that had six tits. And six bandeau bikini tops.

AD: I would love to see that.

SAM: I don’t know if there’s any documentation of it, it was ridiculous. But I guess the starting point for any project has always been a piece of garbage that I found, a shiny bit of crap. And that’s how so many of the old Arabic poems start: with a dropped earring, or the abandoned abode of a loved one. And I have that poignant, bittersweet feeling of being an observer, left behind, which has always been the starting point for a story or for a work.

Nonlinear time is extremely important too. Not thinking about time in that literal sense is something that my work has been grasping towards, like you were saying with the edits and stuff. The films are more like wanderings, and not necessarily structured with a beginning, middle and end.

AD: This reminds me of Hélène Cixous’s way of thinking about literature. You reference science-fiction quite a lot. Are there specific sci-fi authors or filmmakers that informed your way of thinking about storytelling and non-linearity?

SAM: An extremely obvious one is Wild Seed (1980) by Octavia Butler, which explores the expansiveness of lifetimes. It happens over many centuries, but there’s this groundness in, for example, recognising someone who you’ve known before, but they’re in a different body. And that, as well as the layering of time, is something that I feel increasingly aware of. Being in isolation during the pandemic, and spending months without seeing anyone, has also led me to a different perspective on time. Especially during those moments of extreme stillness and quiet, I felt that I could access different versions of myself, young and old, and not hold any judgment on them.

AD: I read that you were working on a film called The Marina. Can you tell me more about the project?

SAM: It’s in a limbo stage at the moment. We’re at the point where we should move out of development and into pre-production this winter, but we are still seeing how it’s going to pan out.

I wanted to write a Ballardian Gulf short story that was a read of expats, and explored the relationship between Britain and the Gulf. The short story got me a small development deal with a production company who took it to the British Film Institute. This was five years ago now. And since then, there’s been so many versions of the script but it’s been in development, and that means that it’s been very central to my life and to my work. It’s been keeping me afloat in a lot of ways. It’s a very rich thriller, in the vein of Chinatown (1974) where it’s about these macro things happening and relating to a global scale, but it’s through the stories of these individuals who are building a project called The Marina. It’s like a solarised noir; it’s very bright, instead of dark.

AD: You show your films across cinema, gallery and museum spaces. Do you feel like there are differences in the way you write and think about what you’re filming, depending on where you present them? Is there a specific environment that you prefer?

SAM: That’s really hard, because each one of them is quite different. I feel like some of my videos are meant for a phone, and some need to have a huge screen with surround sound. Sound is central. But I like it to feel intimate. I always want people to feel like they’re alone with it. Because when there’s that direct call from a work, then I’m definitely paying attention to it. I think that’s probably the thing for me, that’s even more important than necessarily the format.

AD: Intimacy is very present in your work, through your voice actually. I remember discovering Tender Point Ruin and hearing you talk, in the film, about footage of a concert in Cairo that we, as viewers, were watching at the same time. That direct narration really created a space for intimacy and vulnerability, I felt like you were bringing me in the video.

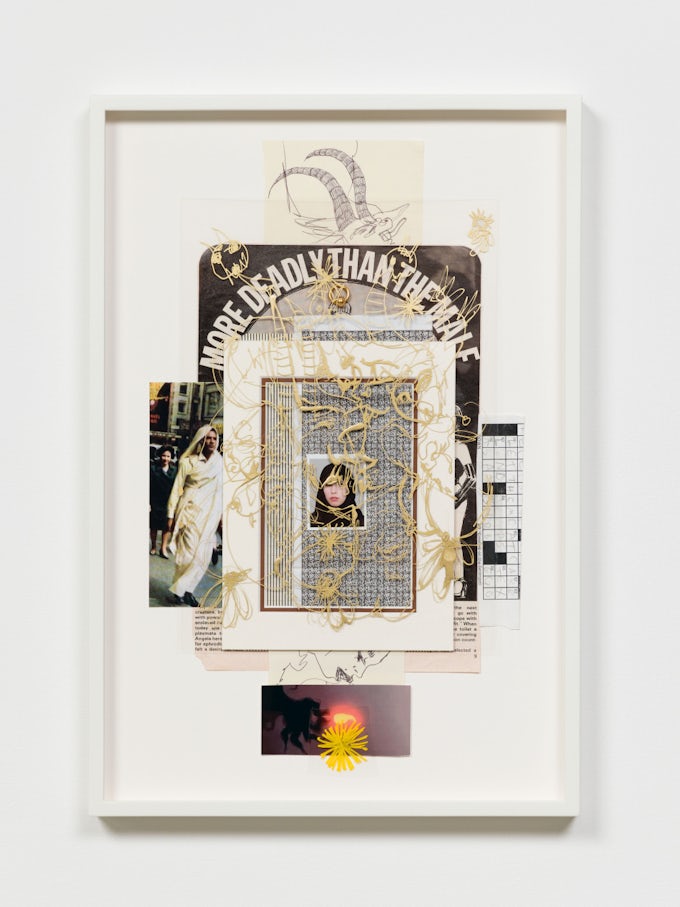

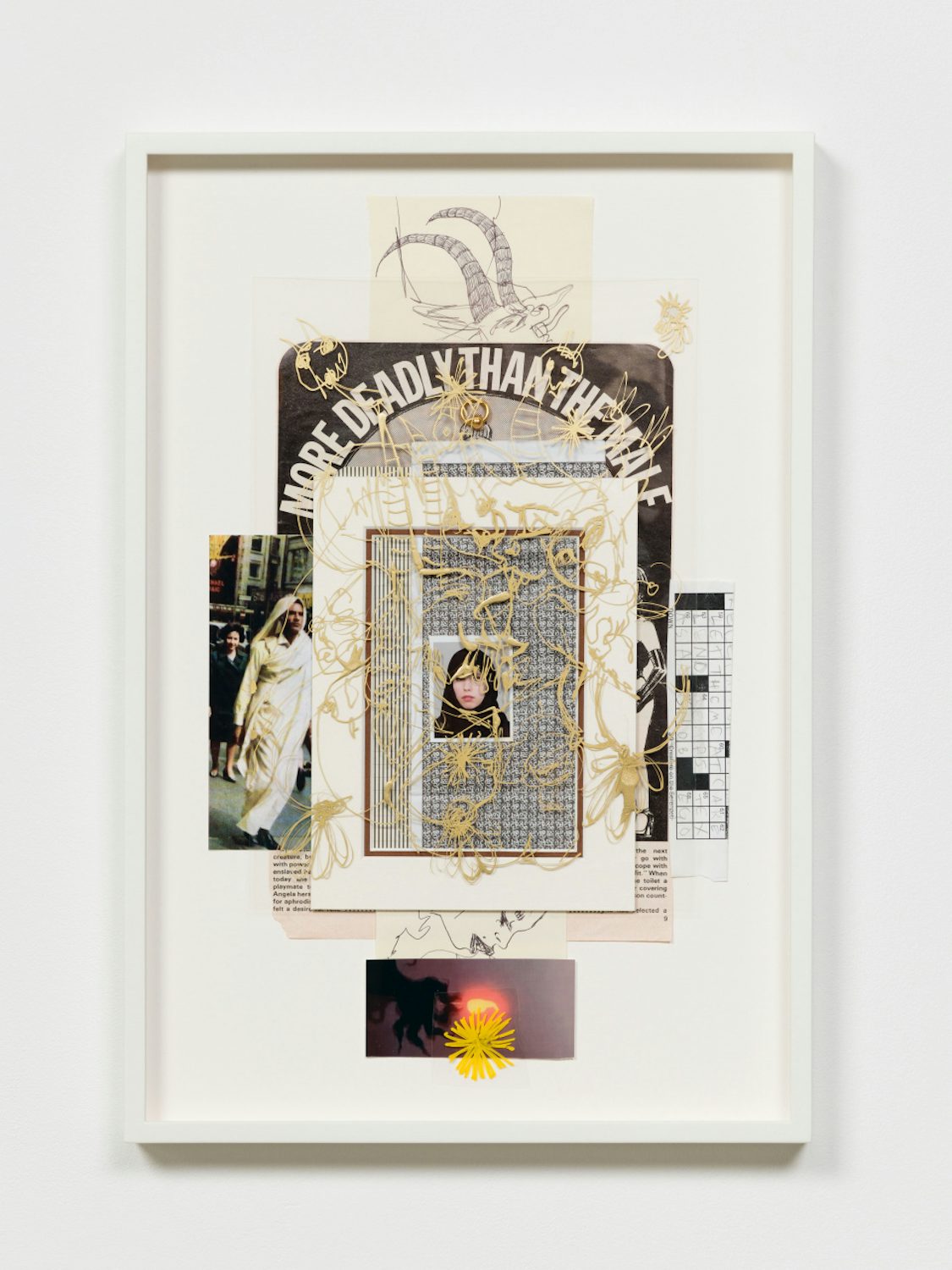

Could you say a few words about the paper collages you are exhibiting at Project Native Informant?

SAM: They feel like a strange 3D edit. I’m so used to working with video and found images that I haven’t used this muscle in a very long time. Actually, I used to make these very angsty collages when I was a teenager. These ones feel almost talismanic. They are extremely dense, and there’re lots and lots of hidden things in them. They are equations, complete stories that can be read. And in a lot of ways I feel like that for that reason, they tie in with my book Sad Sack (2019) and the influence of The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (1986) by Ursula K. Le Guin. 05 The elements of the collages are things that I have literally carried with me since I was a teenager, when I left home. In each one of the frames, or framing devices, there are these layered little like stacks of photographs and bits of books, texts, plastic magazines, toys, shards of old soap boxes. There’s a lot of passport photographs and old IDs – as if spinning garbage into gold. And each one of them is very personal. It feels both good and scary.

Footnotes

-

Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge (trans. A.M Sheridan Smith), London and New York, Routledge Classics, 2002, p. 19.

-

Anthea Hamilton, Sophia Al-Maria, Zadie Xa and Benito Mayor-Vallejo, ‘Wishbone Vision’, Project Native Informant, London, 10 November 2021–22 January 2022.

-

Gulf Futurism was first coined by Sophia Al-Maria and Fatima Al Qadiri in Karen Orton, ‘The Desert of the Unreal’, Dazed Digital [online], 9 November 2012. The topics explored through this notion can also be found in a 2008 essay which looks at the social transformations generated by the oil-fuelled economic shift of the 1980s in the Gulf, a region seen as ‘an uncanny preview of long-imagined futures/nows’. See Sophia Al-Maria, ‘Introduction’, The Gaze of Sci-Fi Wahabi: A Theoretical Pulp Fiction and Serialized Videographic Adventure in the Arabian Gulf [blog],available at http://scifiwahabi.blogspot.com (last accessed on 10 December 2021).

-

Al-Atlal (الأطلال), often translated as The Ruins, is a poem by Ibrahim Nagi which was interpreted by the singer Umm Kulthum and composer Riad Al Sunbati in 1966. The poem relies on a topos of Arabic poetry in which memories, traces and objects are left behind by a lost lover.

-

In her essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction published in 1986, Ursula K. Le Guin challenges the idea that the spear was the first human tool ever created, and rather suggests that it was a bag, a recipient, an empty vessel meant to hold more than what human hands could. Subverting the spear’s phallocentric, heroic and very paroxysmal aspects, the thought behind the carrier bag can also be linked to ways of envisioning storytelling. Far from the ‘weapon of domination’, it can lead to narratives that are nonlinear, that layer thoughts and experiences, with no defined route, no intentional organisation. A carrier bag of fiction rather reveals ‘what people do and feel, how people relate to everything else in this vast sack, this belly of the universe, this womb of things to be and tomb of things that were, this unending story’. Ursula K. Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm (ed.), The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks of Critical Ecology, Athens, GA, and London, The University of Georgia Press, 1996, p. 154.