one february afternoon

we speak about

what it means to be in a constant state of mourning

every day

we mourn the loss

find ourselves in the lack 01

The postscript – that which comes after writing.

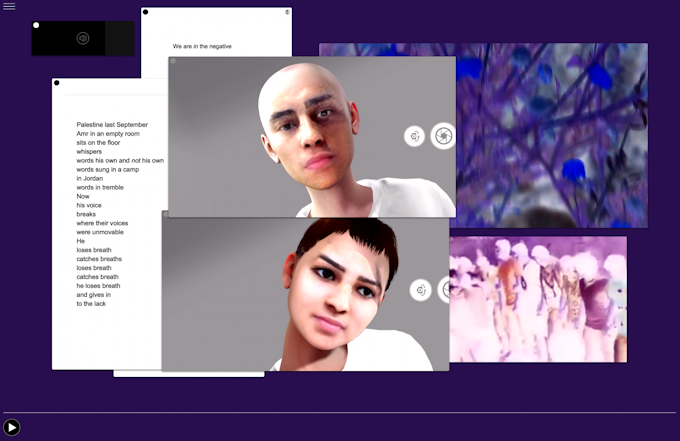

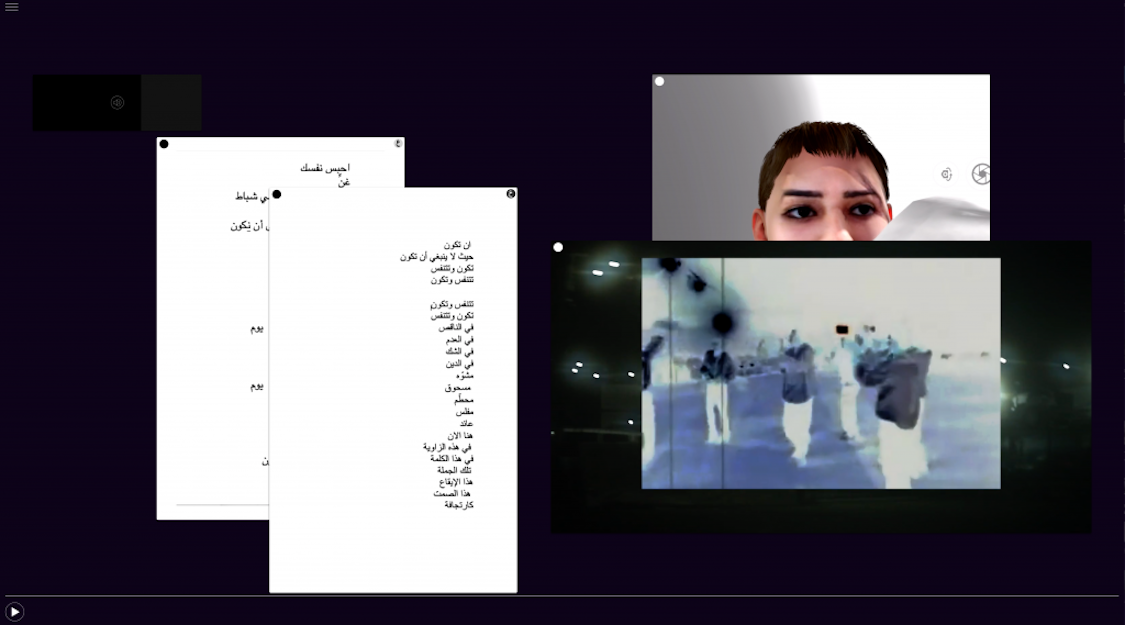

New York and Ramallah-based artists Basel Abbas’ and Ruanne Abou Rahme’s online project May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth paradoxically starts with a postscript. Punctuated with snippets of text reminiscent of the interface of a smartphone note app or a TextEdit desktop window, the first part of this web-based work opens with the epigraph above, which refers to the consequences of the displacement and forced exile of the Palestinian people. As various notes emerge through pop-up windows over the course of the twenty-minute-long Postscript: after everything is extracted, the artists ask, what comes after loss, after grief, after trauma? When, where, and how can we narrate these stories?

Launched in December 2020 as part of Dia Foundation’s Artist Web Projects, May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth has been in the works for nearly a decade. A co-commission with MoMA, the project takes its title from the ‘Infrarealist Manifesto’ (1976), Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño’s call to fight oblivion, to question the art world’s heteronomy, and to subvert complacency and pre-established orders. Bolaño’s fiery words are no stranger to the duo’s practice, as one of their previous installations, The Incidental Insurgents (2012–15), imagined the life of one of the characters from Bolaño’s novel The Savage Detectives (1998) in search of new ways of envisioning political action. Postscript is only one chapter of the project, which includes another digital iteration on the online platform and a physical exhibition that will open at MoMA in April 2022. 02 These subsequent parts feature new performances and videos by the artists and by several Palestinian dancers and electronic musicians (such as Makimakkuk, Haykal, Julmud, and Rima Baransai).

9 PM

New York

May

All I want is to return to that moment

I sketch it out in my head

again and again

Initially, Abbas’ and Abou-Rahme’s web project intended to show and explore recordings originally posted online during the Arab Revolutions in the 2010s, that the artists had methodically saved and screenshotted. Since then, most of these videos have been removed from the Internet, making the artists’ transcriptions a vast and unique digital archive of daily life in the region during the political uprisings. Succinctly present in Postscript, these digital extracts show communities dancing in the streets, singing and protesting in Palestine, Syria, Yemen and Iraq. This new archive keeps alive resistant acts of being, by collecting testimonies that are usually excluded from official and state-sanctioned narratives.

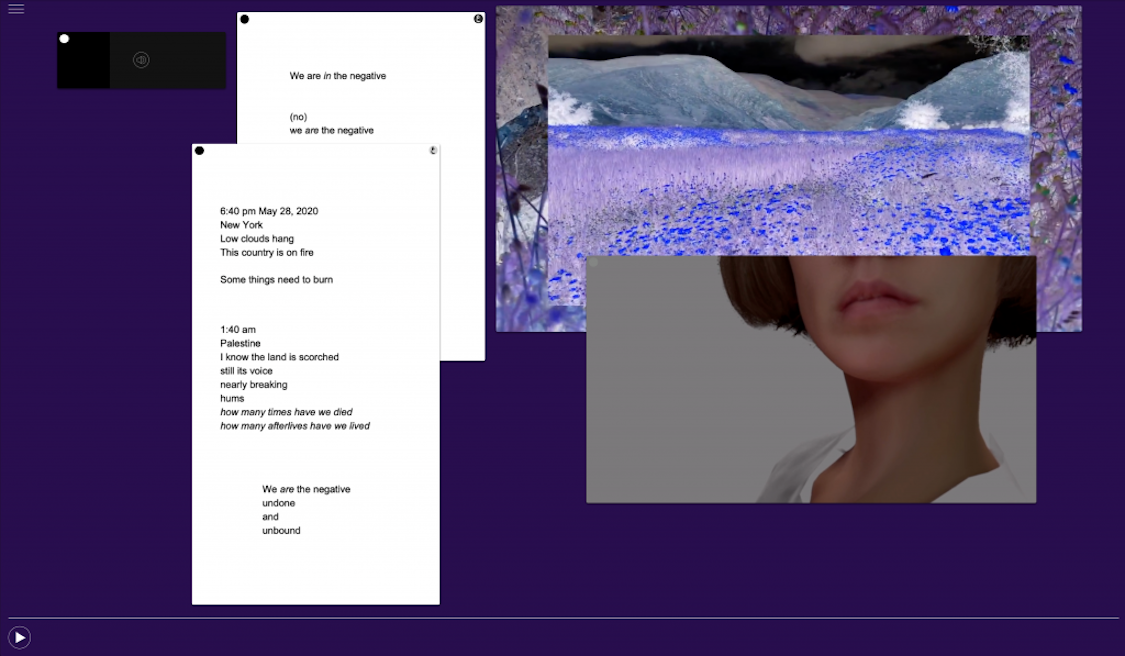

Why, then, to have a postscript amidst all this material? The decision to ‘begin with the ending’ emerged as the entire world was starting to shut down because of COVID-19, experiencing forced stillness and the impossibility to choose where and how to move – a condition not too far apart from the grief described in the first fragment of text. 03 The first chapter of the project is an afterthought to the initial body of collected material, conceived at a time when the artists found themselves stranded in New York City and unable to return to Palestine as borders were closed amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Being responsive to the health crisis in their work and not erasing the context in which the project was going to take place became crucial and urgent, as their archival work started to concur with present and global experiences of loss and mourning.

After everything is extracted

in the lack

in the negative

who is here

after everything is extinguished

Contrary to what one might think while reading the previous paragraphs, Postscript: after everything is extracted is not a gargantuan flux of pop-up videos, collected texts and anxiety-filled tweets that can be evocative of the overwhelming move online and the paroxysm of digital life. Even though the project is bound digitally and takes on a web format, the feeling that emerges from Postscript is far from those caused by a terrifying mass of email notifications or open and infinite tabs pushing further the porous borders of what it means to be productive and in a constant state of alert.

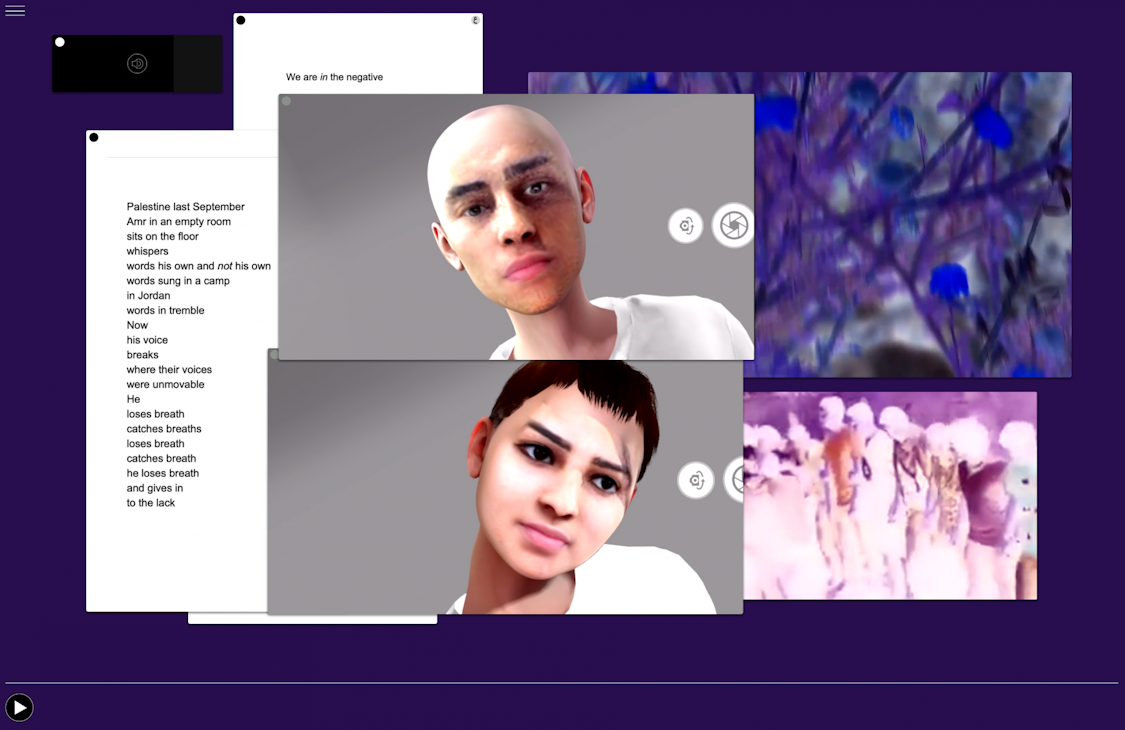

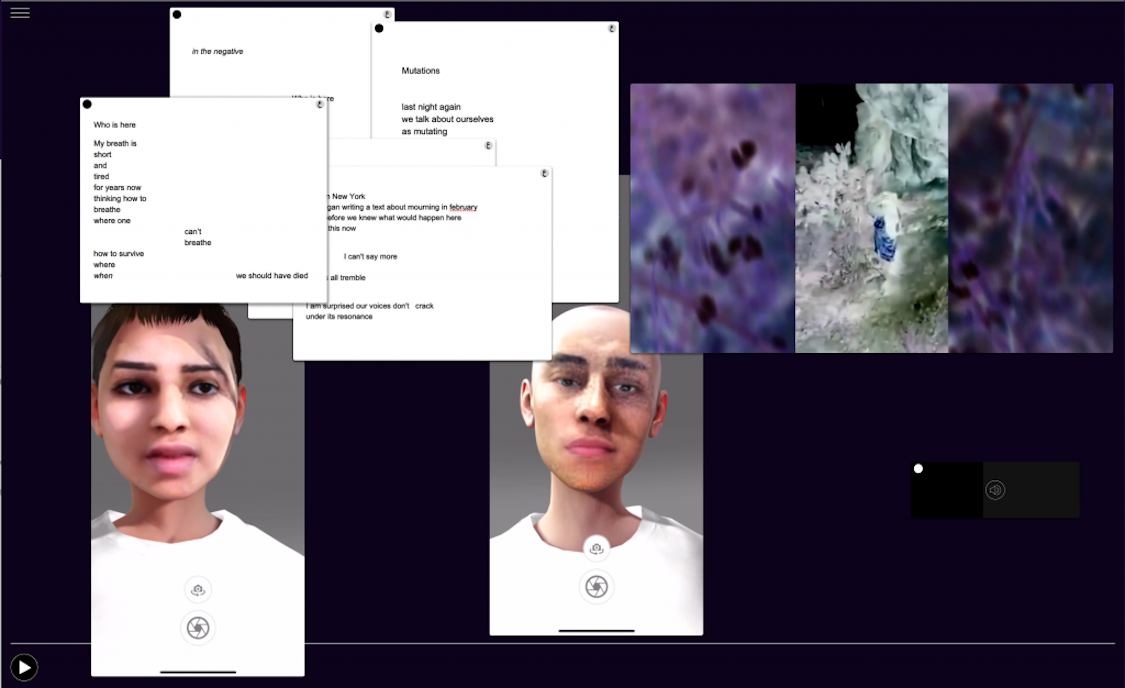

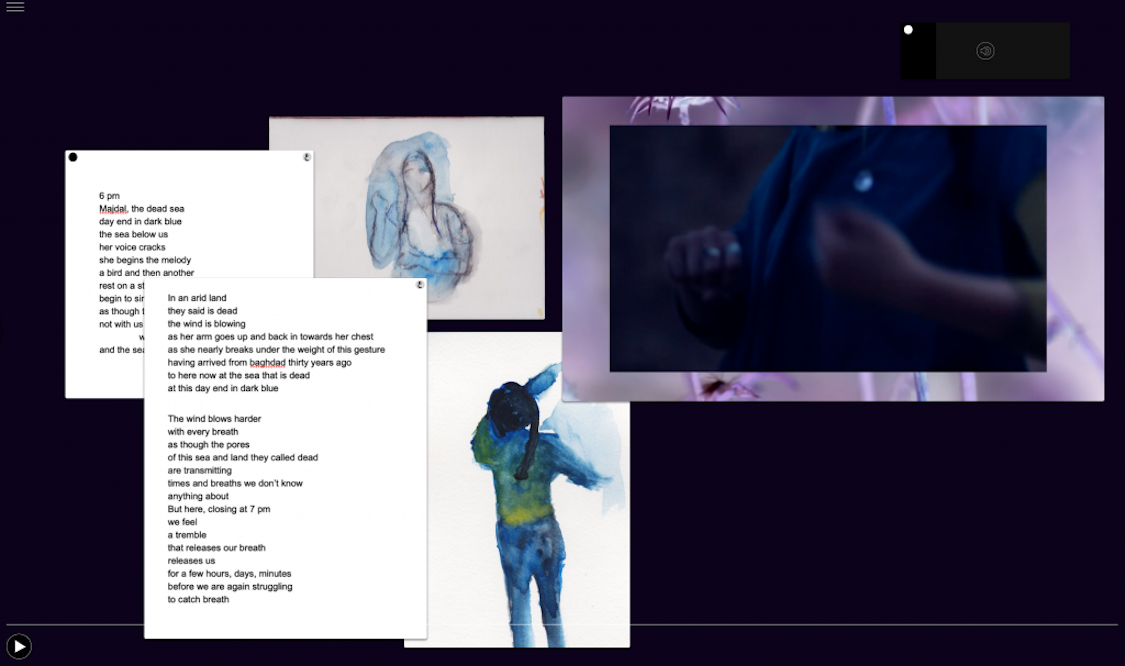

Rather, Postscript is about lingering. Lingering ‘in the negative’ (and quite literally, as many of the images are presented in their negative photographic form), ‘in doubt’ and ‘in debt’, to quote from its unrolling texts. Basel Abbas’ and Ruanne Abou Rahme’s online project unwinds with no rush, to the eerie yet soothing humming and reverb of voices. Tabs appear slowly, in separate layers, giving one the time to contemplate every one of the poetic texts and oneiric sounds. The viewer can pause whenever, choose amongst the six scenes that form Postscript with the taskbar navigation system, close certain videos or texts, and dwell on the ethereal image of a drive at dawn. The blurriness and pixelated nature of the archives appearing on the perpetual purple gradient backdrop participates in the strange quietness – but not silence – of the digital project. Within the cracks and extracts, the artists open a time to digest, process, and acknowledge loss; a time that has been significantly reduced in the midst of the global crisis. Videos of city lights, open fields and dark skies feel meditative, especially when remembering months when the entire world couldn’t set foot outside freely.

and we mourn

again and again

a land that is vanishing

The first chapter of the artists’ new project is a postscript for a story that has been lived but has not yet been written. As it interweaves the melancholic atmosphere of an exceptionally halted world with the persistent and violent realities of Palestinian life under siege, Postscript is full of fragments of videos that loop infinitely as if unable to progress anywhere else, and of sonic glitches and stutters that point out missing information. Postscript does not shy away from the holes in the narrative that it’s bringing to the screen, the repetitive nature of life in forced stillness. It embodies what dispossession feels like. To quote Jean Fisher, ‘when belonging to a place, language, culture and history is violently interrupted, the self has literally no ground from which to speak and hence to narrate itself… Dispossession is in extremis a deprivation not only of the past but also of the will to imagine new possibilities of existence: a withdrawal into the speechless, biological state of what Agamben calls the “inhuman”’. 04

I am failing my body

But I know it remembers

What I am trying to forget

The glitches are also physically represented in the project by two strange avatar figures that slowly appear on screen through two Facetime-like windows. The avatars have populated the artists’ previous projects and are based on low-res images that circulated online of protesters from the March of Return demonstrations near the Gaza borders starting in 2018. 05The images are processed through an avatar-generating software and evolve as the algorithm’s app changes through time. Challenged by the poor quality of the footage, the software interprets the pixelated elements as scars, black eyes and injuries, testifying to the violence of the erasure of bodies, even in online spaces. The unease felt in front of a digital disfigured face, often slit by a white strap, echoes what the anthropologist Ann Laura Stoler calls ‘colonial aphasia’, 06 with regards to colonialist strategies of disappearance. For this author, historical omission is not a passive condition, but a form of ‘aphasia’: not an unintentional loss of memory regarding the histories of a dispossessed population, but rather a form of unequivocal dismemberment, an impossibility and refusal to name colonial violence.

And yet lingering in the fractures, the glitches, and the interstices can also be a powerful space of resurgences. It can be a space of noise that highlights the cracks in established histories. It can be a space that underscores the need to subvert dispossession, to challenge violence against memory, and even against vegetation, like in the case of akkoub, a plant central to Palestinian cuisine and filmed in reverse colours in Postscript, but that is now protected by the Israeli Nature Patrol which forbids its collecting. On the backdrop of autotuned melodic chants, an infinitely looping video of dancers in a circle titled S9 GAZA DANCE seemingly refuses to be swept away, providing an open-ended closure to Postscript. The work’sparticular beauty is intensified by these spontaneous images of people dancing together in the streets, claiming space and freedom of movement by repeating gestures, and embodying what Michel de Certeau would qualify as a resistant ‘tactic’ – which he contrasts to ‘strategies’ – that disturbs the order of everyday life and policed spaces.07

Once we said

we are in search of a new language

now we hold on

to any form of language we can find

to hold these broken parts together

As Postscript assembles a variety of sampled materials into a digital single-channel iteration, the project’s power lies in its ability to intertwine several spaces and times together with no intentional order or hierarchy. Soothing views of Palestinian mountains at dawn overlap with introspective texts of life with COVID-19 in New York. Slow-motion videos of dancers share the screen with purplish iridescent aquarelle bodies. Any attempt to organise temporality or space seems to lose its ground here, even though all the materials are rooted in a very specific and different context. The viewers, too, have a role to play in this newly created space and time as they change the course of what unfolds by switching between Arabic and English texts, or by choosing to mute sound or close videos. These different temporalities mashed-up together reveal a time and space that seems to escape any type of linearity, simplicity or clear-cut dominant narrative of historical events. Watching Postscript unroll feels like staying in something that has been broken, while accepting that something new can emerge from the scattered pieces. This new virtual space is performative: it’s a script that refuses to stay still, to remain unattainable and non-shiftable. It varies according to the choreography of fingers moving across a keyboard to uncover the title of found videos of the Arab Revolutions; it swings to the dance of windows materialising slowly on screen. Postscript: after everything is extracted offers the possibility of a Potential History, to use Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s words. Potential History ‘refuses to inhabit the position of the historian who arrives after the events are over, that is, after the violence was made into part of the sealed past, dissociated in time and space from where we are. Potential History is a commitment to keep alive disobedience to the imperial shutter. Potential History strives to retrieve, reconstruct, and give an account of diverse worlds that persist despite the historicized limits of our world.’ 08 Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme gesture towards a place that doesn’t fit anywhere. A place that doesn’t have an end.

Footnotes

-

All the short texts in italics throughout this article are taken from Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s Postscript: After Everything is Extracted (2020). They are written by the artists. The entire project, May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, is available at: https://mayamnesia.diaart.org/ (last accessed on 7 March 2022).

-

Basel Abbas & Ruanne Abou Rahme, ‘May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth’, MoMA, New York City, 23 April–26 June 2022. The exhibition will travel to the Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zürich, 21 May–11 September 2022; and The Common Guild, Glasgow (dates TBA). The second digital part was released on 5 March 2022.

-

See the epigraph at the beginning of this article.

-

Jean Fisher, ‘Diaspora, Trauma and the poetics of remembrance’ in Kobena Mercer (ed.), Exiles, Diaspora & Strangers, London and Cambridge, MA: Iniva Institue of International Visual Arts and MIT Press, 2008, p.193.

-

For instance At those terrifying frontiers where the existence and disappearance of people fade into each other , 4 channel video, 2-channel sound, 10’54, wooden boards (variable size) live performance (video, vocals, sound), 2019.

-

Ann Laura Stoler, ‘L’aphasie coloniale française. L’histoire mutilée’, in Ahmed Boubeker and Françoise Vergès (ed.), Ruptures postcoloniales, Paris: La Découverte, 2010, p.68.

-

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (trans. Steven Rendall), Berkeley, Los Angeles and London, University of California Press, 1984, pp. 36–39.

-

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperalism, London: Verso, 2019, p.207.