Stan Douglas had pioneered film and video installations inside the gallery walls in the 1980s, before the ‘cinema of exhibition’ – to borrow critic Jean-Christophe Royoux’s term – became a notable trend in artists’ moving-image work since the 1990s. 01Indeed, Douglas’s major works of the 1990s and 2000s led this trend in their attempts to renew the space and time of narrative cinema in ways that transcend the confines of the standardised cinematic apparatus in the movie theatre. In so doing, they also attempted to transform the perceptual and mnemonic dimensions of cinematic spectatorship, whose canonical model is predicated upon the stably intertwined coordination of the frontal screen, a single projector and a limited span of a film’s running time. In Between Film, Video, and the Digital: Hybrid Moving Images in the Post-media Age (2016), I proposed ‘spatialization (materializing the spectatorial experience of the film image, montage, and narrative in the theatrical or architectural forms of screen-related apparatuses) and temporalization (manipulating the time of the image by means of digital video’s capacities) as two key operations that video technologies execute in adopting and altering the components and historical traces of cinema’.02In this vein, I characterised Douglas’s ‘recombinant’ video installation works (pieces that combine narrative units – scenes, dialogues, soundtracks, visual cues, etc. – that originate from other existing materials such as film, television and literary or historical texts) as being able to ‘re-temporalize cinematic narrative to the extent that goes beyond the viewer’s threshold of perception’. 03

In revisiting Douglas’s past oeuvre at a time when post-cinematic works have become commonplace thanks to the growing intersection of cinema and contemporary art on the one hand and the proliferation of digital expressions and computational techniques in the production and consumption of moving images on the other, I would characterise it as prefiguring a specific concept of post-cinematic practices. What I call the ‘cinema of operations’, as suggested by the use of the word ‘operation’ in my previous take on Douglas, indicates various and often interrelated practices that have the effect of expanding and redrawing the formal, aesthetic and technical boundaries of normative cinema by building upon and foregrounding their ‘operations’. The Oxford English Dictionary defines ‘operation’ as the work or act in a system or machine (‘the way that parts of a machine or a system work’ or ‘an act performed by a machine, especially a computer’),04its etymological root, Latin operate, denoting ‘to work or labour’ and ‘to have effect’.05Expanding on these definitions, an artefact considered as a cinema of operations would be conceived as one that brings to the forefront its particular system or machine, its specific set of rules governing how the system or machine works, its desired acts or functions, and its desired technical and aesthetic effects.

A key feature of the cinema of operations is thus its ‘exhibitionist’ tendency to draw viewers’ attention to the processes of the machine or system, so that they appreciate and analyse its technical and aesthetic effects, including visual wonder, surprise and uncanniness. For this reason, it is read as revivifying what Tom Gunning’s canonical concept of the ‘cinema of attractions’ indicates, namely, the early cinema’s imperative to display the technical properties of the cinematic apparatus rather than to unfold a coherent story as in the case of the classical narrative cinema. 06 In his further elaboration of the exhibitionist strategy of the early cinema, Gunning draws the concept of ‘operational aesthetic’ from historian Neil Harris, who studied P.T. Barnum’s public exhibition of elaborated hoaxes and curious mechanical objects in his American Museum in New York from 1841 to 1865. What Harris meant by the concept was the way that Barnum had exemplified the general fascination with appreciating the operational processes of technologies and scientific devices in the nineteenth century.07Gunning takes this underpinning of the operational aesthetic to explain the ways in which the cinema of attractions solicited viewers’ attention to how its apparatus worked and what kind of visual effects it produced. ‘This show-biz strategy, called the “operational aesthetic” by Neil Harris,’ Gunning writes, ‘reflected a fascination with the way things worked, particularly innovative or unbelievable technologies.’08

The standardised cinema is built upon a specific set of protocols, such as how the projector works, where the projector and the screen should be installed, and how the architectural and atmospheric setups of the auditorium should be made. They are applied to not only the technological and institutional components of the cinematic apparatus, but also to a set of rules governing the functioning of the devices used for film production (for instance, the 180-degree rule) and the organisation of audio-visual materials (for instance, editing conventions such as continuity editing and parallel editing). The concept of operations, then, has been more salient in the historical endeavours to make visible, modify or transcend the protocols and workings of the normative cinematic apparatus, and, by extension, to design a machine or system that is based on its particular conventions or functions, and which produces a set of effects that evoke or transform the apparatus’s desired aesthetic effects. Such endeavours can be found in numerous avant-garde practices of ‘expanded cinema’ since the 1960s, which Gunning indeed considered as a domain in which the cinema of attractions persisted after the establishment of the classical narrative cinema,09particularly in works that, for instance, set up multiple projectors and made visible their operations and those of the artist or film-maker as performer in a live setting.

‘Paracinematic’ works such as Ken Jacobs’s Nervous System (a performance whose optical illusion is derived from projectors without filmstrip, 1975–2000), Anthony McCall’s Line Describing a Cone (a sculptural film composed of projected light, 1973) and Paul Sharits’s ‘locational films’ (such as Shutter Interface, 1975 and Dream Displacement, 1976 that employ multiple projectors in the exhibition space), to name just a few, sought, in the words of film scholar Jonathan Walley, ‘cinematic properties outside the standard film apparatus’ in opposition to the medium-specific premise of film as art, inasmuch as they attempted to locate ‘cinema’s essence elsewhere’.10These works were in line with the extremely physical-materialist practices of artists such as Malcolm Le Grice, Birgit and Wilhelm Hein, and Lis Rhodes in Europe, which film historian Pavle Levi has called the ‘cinema by other means’ – a diverse array of cinematic practices ‘using the tools, the materials, the technology, and the techniques that either modify and alter, or are entirely different from those typically associated with the normative cinematographic apparatus’. 11 The importance of operation as both mechanical functioning and conceptual device, or as both automated functioning and manual labour, in the expanded cinema of the 1960s and 70s is still evident in many contemporary film projection performances and film installations based on the creative transformation of the components of the cinematic machinery and on the technical rules applied by a film-maker or artist to the workings of such components, both of which aim to explore and refashion the representational, perceptual or psychic effects of cinema. Bradley Eros, a film-maker who has investigated the potentials of expanded cinema in his live projection performances, characterised himself as the technical and conceptual operator of his projection system with the following words in 2005: ‘Fully conscious of the theatre of operations, a cinema comes into being as a “form that thinks” constantly re-inventing itself as a neurophysiological, image-restructuring, sonic-synaptic system.’ 12

What Walley and Levi commonly suggest about the traditions of expanded cinema – that is, the influence of ‘other’ tools, materials and techniques than those of the standardised cinematic apparatus (Levi) or of its ‘elsewhere’ (Walley) as a key driving force of the expanded operational cinemas in the avant-garde tradition – allows one to think of another key context from which the idea of operation has increasingly been developed, elaborated and studied. In the twenty-first century, what has fuelled ‘other’ tools, materials and techniques is digital and computational media. The ‘elsewhere’ comes from both the images that the media produce and the media’s underlying functioning. Harun Farocki’s now-famous concept of the ‘operational (or operative) image’, new kinds of images that ‘do not represent an object, but rather are part of an operation’,13suggests the two features that distinguish these images from those of photochemical imagery. First, the images are ‘operational’ in the sense that they ‘act’ in itself and perform certain ‘functions’ or ‘effects’ of machines implemented in a wide variety of social, scientific, industrial, administrative and military workplaces (images of CCTV, facial recognition, medical operations, predator drones, to name just a few), as well as in entertainment (images of video games); and second, for this reason, the images are devoid of the aesthetic effects that photochemical images are expected to convey, including representing the world. Trevor Paglen neatly summarises these two features in his comment on Farocki’s work: ‘Instead of simply representing things in the world, the machines and their images were starting to “do” things in the world.’14Film scholar Volker Pantenburg advances Paglen’s view, arguing that the functionality of the operational image derives from its underlying algorithms and the rules on which they are based, all of which are foreign to photochemical images whose production is rooted in the interplay of mechanical automatism and human observation. As Pantenburg elaborates: ‘The operational image is not only a “working image”, but also an image that is the result of a calculation, as opposed to other forms of image production.’15What is more profound is that operations performing certain functions as built-in components of the computer act as representations in themselves, to the point that they incorporate traditionally cinematic forms of accessing and capturing reality in favour of acting on the world. Lev Manovich has noticed this point in his now canonical The Language of New Media (2001) as follows: ‘As computer culture is gradually spatializing all representations and experiences, they become subjected to the camera’s particular grammar of data access. Zoom, tilt, pan and track: we now use these operations to interact with data spaces, models, objects and bodies.’ 16Manovich’s observation seems to anticipate the present situations in which Artificial Intelligence-based machine-learning systems have increasingly infiltrated the domains of film production and preservation encompassing editing, visual effects and restoration, 17 and the images of the operations of desktops, social media and CCTV have occupied Hollywood’s genre film-making to the point of soliciting viewers’ attention and identification, as evidenced by the recent sequels of Paranormal Activity franchise (films produced since Paranormal Activity 3, 2011), two Unfriended films (2014 and 2018) and Searching (2018). 18

While these new types of post-cinematic practice attest to the increasing spread of what I call the cinema of operations, a question that arises here is whether or not the impacts of digital and computational media diminish not only the operations of the mechanical and technical components of traditional cinema but also the conceptual and aesthetic operations of the film-maker that allow them to devise their own system and to produce their desired cinematic effects. My answer is absolutely no. In this, I follow media scholar Ian Bogost’s formulation of the video game as a cultural form based on the ‘unit operations’ of the computer and its underlying algorithms, and his broad characterisation of such unit operations. For Bogost, ‘Rather than attempting to construct or affirm a universalizing principle, unit operations move according to a broad range of diverse logics, from maximizing profit to creating new functional capacity. Such a broad understanding of the operation is required to facilitate the common processes of the artistic and technological acts.’ 19 In this vein, Stan Douglas’s film and video installations in the 1990s and 2000s are viewed as a cinema of operations that stem from self-devised projection systems based on either his creative implementation of film cameras or multiple projectors, or from his adoption of the algorithmic playback technology. Producing his conceptual logics of juxtaposition and permutation, the systems are geared towards creating new functions for projecting cinematic moving-images, thus destabilising the spatial and temporal parameters of cinematic narrative and unsettling its representational and mnemonic elements.

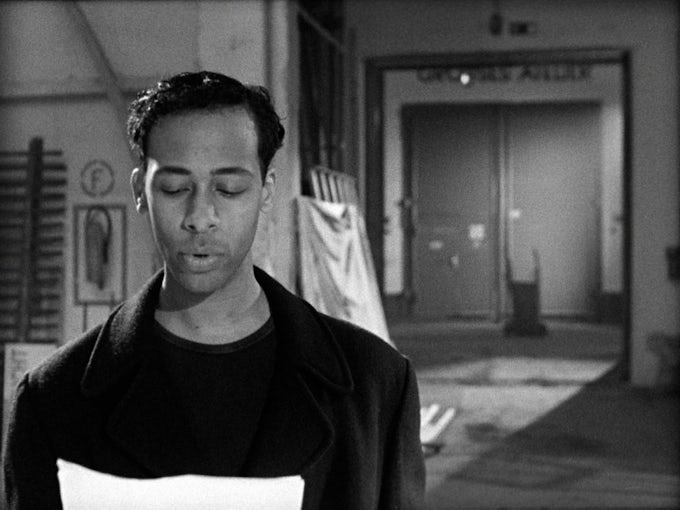

Der Sandmann (1995) and Inconsolable Memories (2005) employ two 16mm film projectors in a way that diverges from both the normative projection of cinematic narrative and the expanded cinema practices of the 1960s and 70s aimed at investigating the material, technical and perceptual effects of cinema. For Der Sandmann, Douglas employed a sophisticated combination of shooting and projection to depict the split psyche of a male figure named Nathanael, who returns to the Schrebergarten (allotment) in Potsdam in which he resided in his childhood. In presenting Nathanael’s psychic disorientation caused by a mysterious old man he had seen in the garden in the past (that is, the sandman), as well as his haunting appearance in the garden that Nathanael visits in the present, Douglas used a motion-control camera that was capable of filming the two gardens in a continuous 360-degree pan. The two takes, one of the old garden and the other of its contemporary counterpart, were then duplicated and combined with a pair of projectors each occupying different sides of the same screen. Accordingly, only one half of each projector’s image is thrown onto the left and right side of the screen, with its other half blocked out. This device successfully produces a ‘temporal wipe’ effect, as Douglas himself writes. ‘As the camera passes the set, the old garden is wiped away by the new one and, later, the new is wiped away by the old; without resolution, endlessly.’20The subjectivity of Nathanael and the Sandman is placed within the repetition of inscription and erasure. Aided by the looped mechanism of projection, the Sandman does not cease to reappear as he disappears into the seam in the middle of the screen – or between the two projected images. The seam brings the viewer back to the materiality of filmic media that is allegorised by the piece’s thematic and formal doubleness of past and present. As with the unfolding of cinematic space, a shot is required to wipe out its preceding shot on the screen space during its linear progression driven by the projector. Douglas translates this technical convention of cinema into a reworking of its media technologies, an elaborate and idiosyncratic combination of camerawork and looped projector. He does so by dealing with the filmed sequence of the scenes like two separate tracks and condensing them into the two-channel projection, in such a way that is not bound to the theatrical projection of film.

Douglas’s innovative conceptual operation of the two projectors is repeated in variation in Inconsolable Memories, through a different mechanism and with a different aesthetic effect. For this work, Douglas used two intermeshing 16mm reels that have their own self-sustained alternations of black and white film sequences and blank-film parts, different in length – one is a 28 minute, 15 second, 5-part loop, while the other a 15 minute, 57 second, 3-part cycle. Douglas projected both uneven loops onto a single screen simultaneously, so that their ordering produces 15 permutations that last for 85 minutes in total. Each loop in Inconsolable Memoriesis a narrative thread consisting of a closed set of filmed scenes, each with a predetermined duration. Thus, in large part, the combinational system in this piece sets in motion alternations between two discrete temporal units, except for moments of partial congruence – for instance, when the visual track of one loop is permeated with the soundtrack of the other. Deploying critical arrangements of visual and audible elements, this system plays out a complex adaptation of Tomás Guttièrrez Alea’s 1968 film, Memorias del subdesarrollo (Memories of Underdevelopment), set in 1962, during the period of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Inheriting almost all of the formal and stylistic devices from the original film, such as internal monologue, unexpected flashbacks and temporal ellipses, Inconsolable Memories reassures us that Douglas’s consistent interest in the ruins and remnants of history – as well as the imaginary reconstruction of places haunted and split by them – hinges on a configuration of the self, a subject who is at odds with his or her surroundings and destined to hover between multiplied temporalities or fractured zones. It is this subjectivity – that is, the subjectivity of a bourgeois anti-hero named Sergio who decides to stay in Havana after the Cuban revolution – that Alea’s film and Douglas’s repurposing share. But Douglas differs from Alea in his way of bringing to life this fractured subjectivity. His Sergio is stripped of the autonomy of subjectivity that Alea’s Sergio more or less maintains: the consciousness of the latter is informed by his voice-over as he views his outer world, while the viewpoint and inner monologue of the former are subjugated to the uneven operation of two 16mm reels that trigger a circle of permutations.

Sarah Durcan reads the pattern derived from the syncopated double projection of two 16mm films in Inconsolable Memories as the ‘algorithm controlling the permutation of [the work’s] narrative’, summarising its effect as ‘a mechanism of variable circularity, constantly providing a menu of churning narrative combinations, yet never evolving beyond the principal narrative events in the shorter film loop. Therefore, the viewer can discern a pattern of sorts behind the superficially random combinations of narrative scenes as the film continues.’ 21 Durcan’s association of the celluloid projection system to the ‘algorithm’ is compelling in that Inconsolable Memories is a variation of what Douglas has termed ‘recombinant’ works. He has customarily used various materials from novels, films and TV dramas – for instance, the Vancouver-produced CBS TV drama series The Clients (1968) for Win, Place or Show (1998), and Norman Foster’s war-time thriller Journey into Fear (1942) and its 1975 remake by Daniel Mann for Journey into Fear (2001) – to create new artefacts that offer a means of mediating on the places they represent and on which they rest.

Douglas’s conceptual operation applied to these adaptations, then, resides in the fact that he introduces a putatively infinite number of combinations of the constitutive elements of each piece. He first films a series of sequences, then dissects them into smaller units – soundtrack and image track or individual scenes, for instance – and redistributes them into two or more channels that are connected to different playback devices. Each of those devices has a different temporality and duration, thus their synchronised operations produce different combinations of those units from loop to loop. In the case of Win, Place or Show, Douglas’s transfer of his filmed scenes to four DVD players connected to a synchronous starter and an interval switcher – two devices that function to vary the combination of the looped material – resulted in an almost infinite and random expansion of their montages (to more than twenty-thousand hours for 204,203 variations).

This recombinant narrative is inspired by Douglas’s application of the computer to select certain elements – such as characters, situations, rules and story paths. Instead of the hierarchical and centralised control that is widely applied to hypermedia narrative artefacts (in which the viewer or player is offered what is actually a limited set of actions), each of Douglas’s recombinant works is predicated on contingency (in the sense that its elements are combined and recombined) and partial perspectives (in the sense that each viewer comprehends its spatiotemporal construct), while turning the viewer’s attention to its technological system. In so doing, Douglas assumes that our understanding of a place in our engagement with the media-produced narrative depends as much on its temporal parameters as on spatial ones. As those parameters include such temporalities as randomness, difference, infinity and recurrence, his recombinant narrative defies the notion that events happening in a fictional – imaginary and diegetic – place unfold in a chronological order. Characters in this sort of narrative are depicted as stripped of the power of controlling those events: their conflicts remain unresolved and repeated (Win, Place or Show), or the achievement of their goal is infinitely delayed (Journey into Fear). By acknowledging the contingency and openness of the diegetic world this way, and by challenging the myth of viewers’ total control over the artwork with a putatively infinite number of permutations during their visit to the installation site, Douglas’s recombinant works make a cinema of computational operations that function to reinvent montage in a nonhuman manner and to redefine the temporality of cinematic storytelling. These functions, however, deserve to be viewed as prefiguring an alternative to the mainstream version of interactive cinematic storytelling, such as Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018), whose choose-your-own-adventure format operated by Netflix’s invisible algorithms eventually leads to the repetitions of a limited set of narrative paths despite its desired function to allow viewers to make decisions at various junctures. Again, this alternative validates that a cinema of operations based on the computational processes and methods needs to involve not only technological but also artistic or conceptual acts in order to expand or redraw the formal and aesthetic boundaries of cinema in the post-cinematic condition.

Footnotes

-

Jean-Christophe Royoux, ‘Cinéma d’exposition: l’espacement de la durée’, Art Press, no.262, November 2000, pp.36–41.

-

Jihoon Kim, Between Film, Video, and the Digital: Hybrid Moving Images in the Post-media Age, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016, p.46.

-

Ibid., p.291.

-

‘Operation’, Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries [online], available at https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/operation?q=operation (last accessed on 23 February 2022).

-

‘Operate’, Online Etymology Dictionary [online], available at https://www.etymonline.com/word/operate (last accessed on 23 February 2022).

-

Tom Gunning, ‘The Cinema of Attraction[s]: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde’, Wide Angle, vol.8, no.3/4, 1986, pp.63–70, reprinted in The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, ed. Wanda Strauven, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006, pp.381–88.

-

See Neil Harris, Humbug: The Art of P.T. Barnum, 1st ed., Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1973.

-

T. Gunning, ‘Crazy Machines in the Garden of Forking Paths: Mischief Gags and the Origins of American Film Comedy’, in Classical Hollywood Comedy, ed. Kristine Brunovska Karnick and Henry Jenkins, New York: Routledge, 1995, p.88.

-

‘In fact the cinema of attraction[s] does not disappear with the dominance of narrative, but rather goes underground, both into certain avant-garde practices and as a component of narrative films, more evident in some genres (e.g., the musical) than in others.’ T. Gunning, ‘The Cinema of Attraction[s]’, op. cit., p.382.

-

Jonathan Walley, ‘The Material of Film and the Idea of Cinema: Contrasting Practices in the Sixties and Seventies Avant-garde Film’, October, no.103, Winter 2003, p.18.

-

Pavle Levi, Cinema by Other Means, New York: Oxford University Press, 2012, pp.xii–xiii.

-

Quoted in J. Walley, Cinema Expanded: Avant-Garde Film in the Age of Intermedia, New York: Oxford University Press, 2021, p.100. Walley’s monumental study offers various case studies of contemporary expanded cinema practices whose structures, functions and effects can be deemed as cinemas of operations.

-

Harun Farocki, ‘Phantom Images’, Public, no.29, 2004, p.17. For a helpful study of operational images as informing a new approach to image and media, see Aud Sissel Hoel, ‘Operative Images: A New Paradigm of Media Theory’, in Luisa Feiersinger, Kathrin Friedrich and Moritz Queisner (ed.), Image-Action-Space: Situating the Screen in Visual Practice, Berlin: Walter De Gruyter, 2018, pp.11–27.

-

Trevor Paglen, ‘Operational Images’, e-flux Journal, no.59, November 2014, available at https://www.e-flux.com/journal/59/61130/operational-images/ (last accessed on 23 February 2022).

-

Volker Pantenburg, ‘Working Images. Harun Farocki and the Operational Image’, in Jens Eder and Charlotte Klonk (ed.), Image Operations: Visual Media and Political Conflict, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017, p.52

-

Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001, p.88.

-

Of many recent applications of AI to film production and restoration, two well-known examples are Martin Scorsese’s use of it to decrease actors’ age in Irishman (2019) and YouTuber Denis Shiryaev’s use of machine learning to colourise and enhance a collection of films by the Lumière brothers, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YZuP41ALx_Q (last accessed on 23 February 2022).

-

For an insightful study of the post-cinematic aspects of this type of film, see Shane Denson, Discorrelated Images, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020.

-

Ian Bogost, Unit Operations: An Approach to Videogame Criticism, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008, p.8. Emphasis the author’s.

-

S. Douglas, ‘Der Sandmann: Project Description’, in Diana Thater et al., Stan Douglas, London: Phaidon Press, 1998, p.128.

-

Sarah Durcan, Memory and Intermediality in Artists’ Moving Image, Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021, p.91.