To mark the 2012 inauguration of the Louvre’s new wing devoted to the Department of Islamic Art, in Paris, Lebanese artist Walid Raad was invited as a resident artist to produce an exhibition in response to the museum collection.01 Raad developed a mixed-media installation that included a video of some objects in the collection as they underwent an unforeseen metamorphosis, and a series of metal cut-outs that reproduced the contours of typical museum spaces. Suspended from the ceiling, the silhouettes floated in mid-air where they were hit by neon vertical lights casting linear shadows of doorways and corridors onto the walls and the floor of the Salle de la Maquette.02 This spectral doubling of the museum architecture, dramatically intensified by the projected shadows, both echoed and highlighted the framing function of the gallery, its crucial yet often occluded role in the definition of artistic and historical value. Exhibited in 2013, the installation was tellingly titled Preface to the First Edition.03

Jacques Derrida discusses the irony of prefaces in the extended preface to his 1972 book Dissemination. A text written after but intended to be read before the main text, Derrida points out how prefaces seem to have always been composed ‘in view of their own self-effacement … [p]receding what ought to be able to present itself on its own’.04 Although typically viewed as an external and even negligible element, prefaces, both authorial or allographic, perform an important hermeneutic function in extending and reframing the text proper, often revisiting it through the eyes of a present to which the new edition is addressed. Together with other peripheral elements – titles, appendixes, footnotes, but also book covers, illustrations and other graphical elements – prefaces are an instance of what literary theorist Gérard Genette calls the paratext. Paratextual elements, as Genette writes, serve ‘to ensure the text’s presence in the world, its “reception” and consumption’; they are ‘what enables a text to become a book and to be offered as such to its readers and, more generally, to the public’. In view of their liminal status, of their being ‘neither on the interior nor the exterior’ of the text, and yet such an important key to its access, Genette calls these elements ‘thresholds of interpretation’.05

In naming his work a preface, Raad ironically points to the prefatory function of the museum’s commission. As the imperial origins and epistemic foundations of museum collections across the West come into sharper focus – raising inescapable debates about how they should be presented and contextualised, or whether they should be there at all – contemporary artists are often summoned to provide these objects with a critical palimpsest that lends a veneer of performative self-reflexivity to the spoils of colonial plunder.06 Yet, such artistic prefaces, more suited to the new critical exigencies of the historical present, are appended to an already existent exegetic apparatus, bolstered by centuries of practice. In replicating the contours of the museum – those doorways that visually recall Genette’s ‘thresholds of interpretation’ – Raad wittily reveals how not only his artwork, but the institution itself, is already a preface: an introductory, ever-present, yet self-effacing frame guiding our perception of its contents. With its practices of collection, documentation and classification, its technologies of framing and display, the museum presents through its material holdings a particular version of the past, and yet by naturalising such a presentation, cancels out its prefatory function.

Despite its title, Raad’s piece is not a preface to a missing history of art yet to be written; rather it is a caustic epilogue to a history that has already been written.07 It serves as a wry commentary to a canon already established through ‘the power of colonial knowledge-gathering’: the forced severance of objects from the people who made them; their hierarchical classification and the coercive imposition of new meanings, values and uses; the destruction, depletion and continued exploitation of the living contexts (people, cultures, environments) they were once part of.08 The scripted history that the museum tells is haunted by the lack of what could have been read or heard in its place: the omitted violence through which artefacts were acquired; the absence of what was lost or destroyed in the pillage; the lasting traumas that haunt the present; the cultural forms – epistemologies, cosmologies, knowledges – that were discredited, discontinued or forgotten.

Preface to the First Edition is part of a larger, multi-volume project that Raad has been developing since 2007. Titled Scratching on Things I Could Disavow: A History of Art in the Arab World, this miscellaneous corpus of works comprises an interrelated series of narratives, photographs, videos, sculptures, installations, theatrical stagings and performances. As the subtitle hints at, the project both proposes a personal and peculiar history of art in the Arab world and looks at how that history is currently being reframed and rewritten.09 Initiated in parallel to and prompted by the construction of new, internationally integrated infrastructures for the visual arts across the Arab region,10 the project investigates the institutions, historiographical concepts, taxonomies, chronologies, pedagogies and economies that are being developed and elaborated as part of such a process. Instead of the backbone of the archive famously deployed in The Atlas Group (1989–2004),11 in Scratching Raad uses the device of the museum display, the curatorial voice and the gallery tour as means to question art historical narratives and museological practices.12 Notably, most of the series of works that fall under Scratching, are named after one of the different components of a virtual book – in all likelihood an academic publication. Besides a handful of sections of scattered chapters, one finds a disorderly profusion of paratexts: a translator’s introduction, an index, appendixes, footnotes, an acknowledgement, several prefaces to a fast-growing number of editions (one of which in Arabic), a postscript and a prologue. However, the manuscript made up of all these fragments is never conjured in its entirety: the text to which the various addenda refer is the blank centre of the project, the void of an impossible history.

In shaping his works as paratexts, on the one hand, Raad directs our attention towards the material, institutional and discursive infrastructure that, paraphrasing Genette, enables a work to become an artwork and to be offered as such to its viewers and, more generally, to the public. He directs our attention to structures of reception and how they are adopted, adapted and altered. On the other hand, and in line with Derrida’s project of dissemination, Raad’s production of supplements can be seen as a strategy that serves to undo, from within, the master narrative of the art historical canon. Both addition and substitute, for Derrida, supplements create an ungovernable excess: a remainder that has the potential to resist gestures of recuperation within the unitary and totalising structure of the Book.13 Like a homoeopathic treatment that turns the poison into its cure, the uncontrolled proliferation of various kinds of paratexts foils and thwarts attempts of epistemic mastery and containment.

Returns

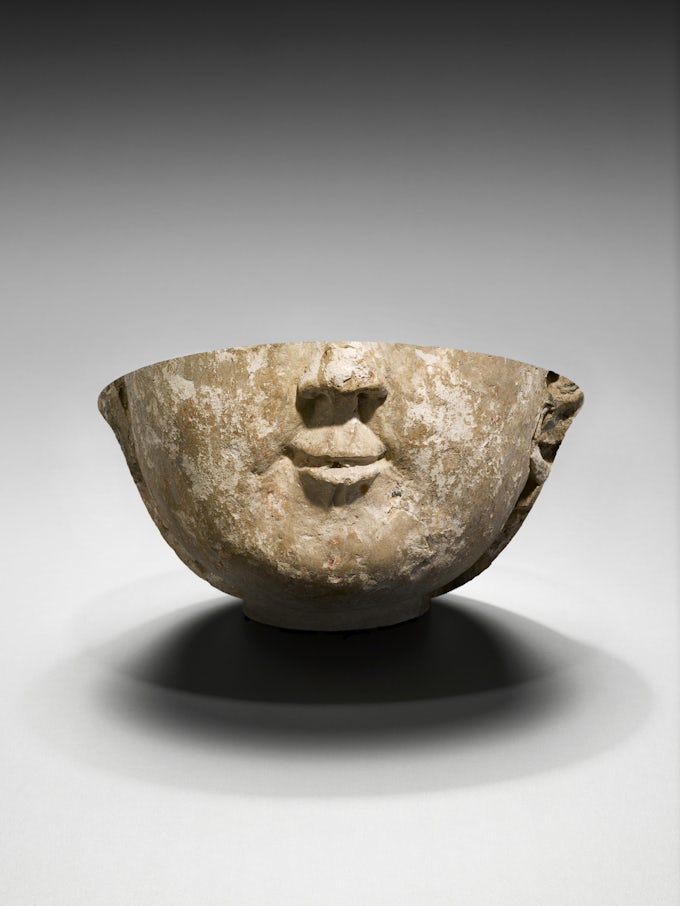

Alongside the metal outlines of museum spaces, for the Louvre’s commission Raad produced yet another preface zooming in on the history of the museum’s collection of Islamic art, its photographic documentation, practices of display and taxonomies of classification, and its programme of loans. Both a video and a set of large photographic prints, Preface to the Third Edition (2013) focusses on the much-publicised loan of 300 canonical objects of Islamic art from the Louvre’s collection of nearly 18,000 artefacts, to its Abu Dhabi branch, designed by French architect Jean Nouvel and part of the ostentatious cultural district of Saadiyat Island. Twenty-two of these objects, Raad predicts, will transform during the journey: they will trade ‘faces’ or skin with each other. Derived from the superimposition of shots taken by the Louvre’s photographer Hugh Dubois, the corresponding set of images (barely perceptible fade-outs in the video or crisp photographic prints) reveal startling transfigurations: the handle of a seventeenth-century Egyptian dagger is overlayed with a floral panel from an Indian lacquered book-cover; a fifteenth-century jade wine cup from Iran is combined with a late-twelfth-century to early-thirteen-century sculpture from the same country; a metal helmet is embellished with the translucent texture of a medieval rock-crystal vessel.

As is customary in Raad’s work-parables, the meaning of the objects’ metamorphosis remains ambiguous. It is both a harbinger of potential regeneration and a signal of irreparable rupture. By breaking free from epistemologies of positive classification that situate each object within the precise coordinates of chronology, geographical location and medium-specific taxonomy, the new hybrids undermine their historicist deployment in museums as exemplary representatives of singular epochs and spaces. They instead unearth stories of intercultural exchange, translation, adaptation and hybridisation that are often sidelined in the tendency to treat artefacts in isolation, as ‘teleological markers in a master narrative’.14 This breaking through the straitjacket of temporal classification becomes all the more significant when considering that these objects are exemplars of Islamic art history, a typical orientalist academic formation emerging in the mid-nineteenth century. An example of what anthropologist Johannes Fabian defines as ‘denial of coevalness’, Islamic art history has tended to confine its objects of study to a premodern past severed from a ‘living tradition’, excluding art produced in the Islamic world after 1800, and therefore influenced by the impact of European colonialism and Western modernisation.15 Besides severing objects from their context of use (and trapping them in the frozen vaults of a museum), this colonial chrono-political strategy has effectively occluded the possibility of recognising local modernising practices emerging out of a re-elaboration of the Islamic tradition.16

The construction of large-scale museums across the region – a phenomenon spearheaded by the oil-producing Arab Gulf states of Qatar and United Arab Emirates, but visible in other countries too – promises to suture this historical break by inverting the ‘centuries-old trickle of antiquities from east to west’.17 It announces the possibility of writing a new preface to Islamic art history – and art history more generally – by ‘delinking’ it from its original source: the Western museum and its epistemic and material entanglements with the history of empire.18 Yet, as the Arab Gulf museums tend to replicate ‘tools, modes and ideas of western museum construction and maintenance’ at the level of cultural praxis, and are ‘tied up in regional geopolitics, economic diversification strategies and military alliances with western powers’ at the material and political level, it’s hard to see how any meaningful ‘delinking’ might occur in such process.19 Franchises of Western institutions, like the Louvre Abu Dhabi, make such claims of delinking even more tenuous. As Hanan Toukan puts it, ‘in the absence of evidence of the production of one’s knowledge on one’s own terms’, the geographical decentralisation of Western museums is not in itself sufficient proof of a decolonial epistemic shift.20 Fuelled by the neoliberal globalisation of capital and connected to programmes of cultural diplomacy, these museums can be seen as continuing, rather than dismantling processes of accumulation and dispossession that were pioneered by their European counterparts. These material and political-diplomatic realities form the backdrop to Raad’s particular form of fictionalised institutional critique. Complicated geopolitical plots, economic transactions and diplomatic exchanges, as well as the stark fact of migrant labour exploitation in the construction of mega-museums, manifest as a series of displacements and deformations in the cultural objects they host – like the mutation of Islamic art artefacts.21

The temporary lease of a small number of objects from the French national museum to one of its franchises in the Gulf is clearly inadequate to address more radical demands for the restitution and repatriation of cultural heritage of the formerly colonised. The loan, as well as the new acquisitions by the Louvre Abu Dhabi and other museums such as, for instance, the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, are more a reflection of the contemporary hegemonic balance of forces in the region and international relations, than a restitution of looted objects to their rightful place of provenance.22 As Islamic art historian Finbarr Barry Flood argues, this ‘putative’ return poses pressing questions about whether the art of a vast and complexly diverse region can be adequately represented in and by one single, now-hegemonic centre, based on its economic and infrastructural capacity to represent.23 In this light, Raad’s tale of transformation might be read as a caution against politically instrumental uses of art in regional constructions of a trans-regional heritage. It points to the fact that the so-called ‘homecoming’ of the collection will not restore an authentic tradition to its place of birth; rather, it functions as a warning of the risk of turning such an invented tradition into the icon of an imaginary cultural continuity.

The objects’ unpredictable mutations signal the profound rift that separates the present from the works’ past and the impossibility of a simple return to the tradition they stand for. As Lebanese writer Jalal Toufic, a key influence on Raad’s work, argues, such a return could only be a return to a ‘counterfeit tradition’.24 Tradition, according to Toufic, does not consist merely in ‘what materially and ostensibly survived the “test” of time’, but ‘becomes delineated and specified’ by what immaterially withdraws as a consequence of a ‘surpassing disaster’.25 If the sole measure for writing art history is focussing on the objects and artworks that have survived and are cherished, one ends up compiling a celebratory script that fails to register absences, voids, disinherited practices and historical traumas. Misconstrued as progress and survival, such history inevitably forgets everything in the past that resists transmission as ‘heritage’ (turath) or ‘cultural treasure’ of the dominant, victorious tradition. Raad’s hybrid objects are impervious to such form of transmission. Their puzzling combinations might be read as a warning, to quote Walter Benjamin, of the ‘barbarism’ that ‘taints the manner in which’ a document of culture is ‘transmitted from one hand to another’, and an appeal ‘to wrest tradition away from the conformism that is working to overpower it’.26

Misrecognitions

Most of the pieces that comprise Scratching revolve around the moment of art’s transmission and reception: the way in which objects and narratives are encountered, passed on, translated, interpreted and represented. Yet, as the tradition these objects were once part of was forcibly interrupted by colonial violence, wars and occupation, transmission is far from smooth. All the ‘reception events’ that Raad stages are chronically haunted by unexpected alterations, delays, withdrawals, literal blockages, occlusions, mistranslations and inconsistencies. Such imperfect reception typically takes place within the museum walls, a space rife with epistemic fissures, interpretative foreclosures and equivocations. Besides being tethered to the circuits of global capital, as we have seen, museums also embody a sedimentation of professional practices, conceptual habits and cultural dispositions that might be said to belong to what Ann Laura Stoler defines as ‘imperial duress’. With its inference of ‘hardened, tenacious qualities’, the concept of duress denotes how the histories and afterlives of imperialism and colonialism continue to actively shape a supposedly postcolonial present.27 It also points to the way in which the ongoing effects of such histories are disavowed through ‘acts of obstruction – of categories, concepts, and ways of knowing that disable linkages to imperial practice’.28 In the discipline of art history, such processes of occlusion often result from a more or less inadvertent reliance on Eurocentric or North-Atlantic taxonomies of cultural difference that are still entrenched in both academic scholarship and institutional apparatuses, in what Stoler characterises as ‘the disparaged remainders cast out from the categories and concepts of colonial narratives’.29 Part of Stoler’s venture is, then, to understand, unlearn and undo these occlusions, so as to open alternative genealogies and ways of thinking otherwise.

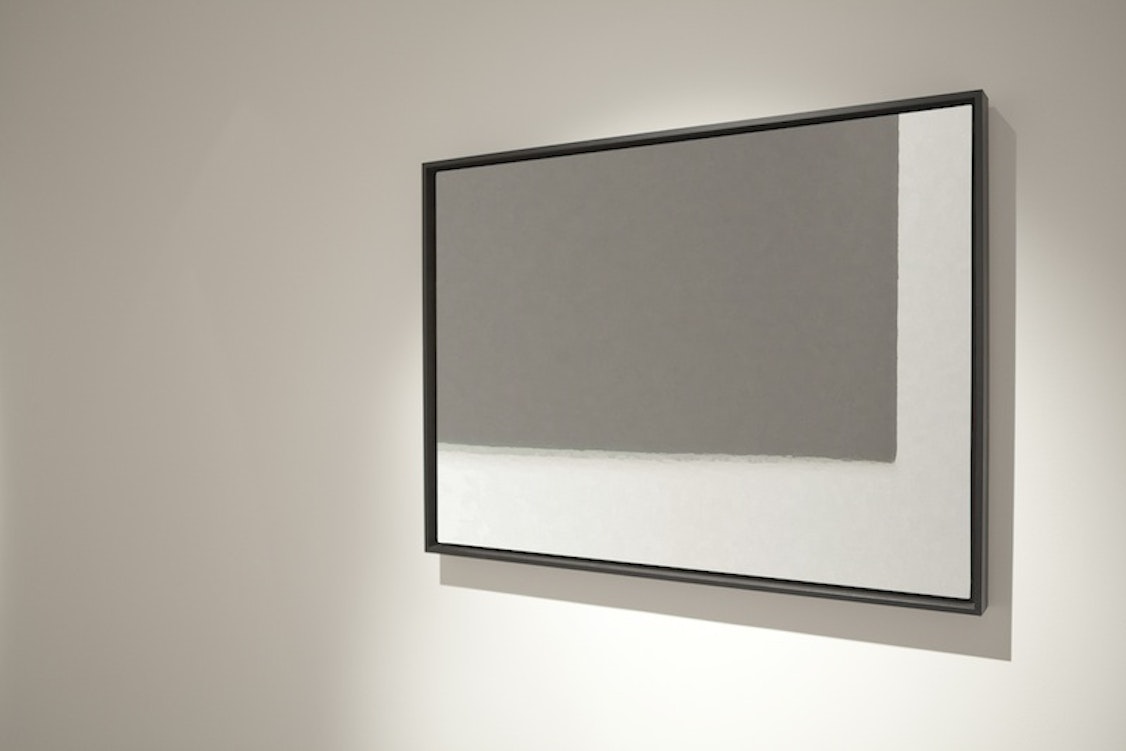

In Raad’s Preface to the Seventh Edition (2012), an instance of such occlusions is rendered as a play of optical illusions and misperceptions. Commissioned by and first displayed in Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, the piece consists of a series of six paintings that, as we learn from the accompanying wall text, were for a long time regarded as ‘canonical examples of early twentieth century Arab abstraction’ and exhibited as such in a hypothetical Emirati museum. Yet, the eventual discovery that each work was in fact a ‘painting of a painting’s shadow’, and thus actually an example of figuration, caused their sudden removal from the museum display. Losing their status as paradigmatic examples of modern Arab abstraction, the paintings were crossed out from the newly formed canon. In one of the versions of the work’s narrative, the paintings are bluntly characterised as ‘paintings of western paintings’ shadows’, making explicit the Eurocentric tendency to consider non-Western modernisms as ‘derivative’ and ‘inauthentic’: a mere, second-rate imitation of a Western template. As Iftikhar Dadi explains, in Western perception and narratives, non-Western modern art has been construed either as ‘a belated and impoverished derivative response to Western modernism’ or as a betrayal of a purported local aesthetic tradition, always invariably situated in the premodern era.30

It is not a coincidence that Raad’s anecdote of misrecognition plays out around specious abstractions. The genre of abstract art is considered more closely associated to an indigenous tradition of premodern Islamic art whose dominant forms are geometry, the arabesque and calligraphy, whereas figurative art – particularly in the format of oil painting – is seen as a nineteenth-century European import, introduced in the region’s bourgeois homes and newly established beaux-arts academies during the colonial period.31 In an attempt to recuperate and cultivate notions of Pan-Arab culture, postcolonial and national histories of modern Arab art, which have often developed through state-centric patronage, have tended to privilege native motifs (like abstraction) and to exclude what does not qualify as recognisable ‘Arab’ art, thus unwittingly echoing Western expectations of cultural ‘authenticity’. In Raad’s tale, the discovery of a figurative inscription in what was hitherto seen as an original example of modernist Arab abstraction disturbs such attempts with a disruptive form that does not map smoothly in constructions of cultural continuity with an autochthonous heritage. On the other hand, however, the paintings of a painting’s shadow also fail to line up with the criteria of medium-specificity, anti-illusionism and self-reflexivity that famously constitute the hallmarks of the Greenbergian version of formalist abstraction and modernist painting. These unclassifiable paintings conform neither with narratives of an unbroken continuity with a fully recovered past tradition nor with Euro-American formalist constructions of modern art as an autonomous and self-reflexive field. They are rather, in Kobena Mercer’s definition, ‘discrepant abstractions’ incommensurable with the ‘institutional narrative of abstract art as a monolithic quest for “purity”’ – whether that be the Greenbergian purity of the medium or the purity of national origins.32 The equivocation of Raad’s narrative points to the necessity of reconceptualising the theoretical construction of the field of abstract art, as well as the histories of other genres of modern art, so that they are made to bear upon different genealogies.

‘Reckoning with genealogies of the modern’ in the postcolony, as Jessica Winegar has amply demonstrated in her study of modern Egyptian art, is fraught with contradictions. Yet, the recognition of the often-omitted plurality of such ‘genealogies’ – the multiple ‘twists and turns’ that the concept of the modern has taken over time – serves as an antidote against singular, historicist narratives that emphasise origins and originality.33 Genealogy is a particularly appropriate term here. As proposed by Friedrich Nietzsche and famously taken up by Michel Foucault, genealogy does not amount to a search for pure origins (Ursprung). The genealogist finds ‘something altogether different’ behind things; not immutable and timeless essences, but rather the discovery that there are no essences to start with. Or, as Foucault would say, that their essence was ‘fabricated in a piecemeal fashion from alien forms’.34 In fact, in reconstructing, for instance, the history of abstraction along divergent or discrepant genealogical lines, one may find cross-cultural routes of exchange and influence that invalidate versions of unilateral borrowing or Euro-American primacy, as well as the tendency to reify culture through a narrative of authenticity. Refusing a search for distilled origins, this genealogical method is tuned in to “differential histories” and “interrupted imaginaries”, as well as ‘those haphazard moments when narratives are revised’.35 In presenting a stereoscopic mode of vision by which a painting can be simultaneously figurative and abstract, Raad makes us see otherwise.

-

Walid Raad / The Atlas Group, Preface to the Seventh Edition _ IV, 2012, archival inkjet print mounted on aluminium Dibond, 29 × 43.5in (73.7 × 110.5cm). © Walid Raad. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York -

Walid Raad / The Atlas Group, Preface to the Seventh Edition _ III, 2012, archival inkjet print mounted on aluminium Dibond, 29 × 43.5in (73.7 × 110.5cm). © Walid Raad. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

***

With its accretion of prefaces and other paratextual elements, Raad’s project denaturalises familiar ‘ways of seeing’ and unchecked conceptual habits within the iterable spaces of the museum. In making visible the ‘thresholds of interpretation’ that always frame our encounter with cultural production and in questioning our capacity to truly access what seems readily available, his speculative fictions work to foreground the contradictory ways in which the reception of art continues to be filtered through cultural mistranslations and colonial holdovers. Recognising such occlusions appears a vital step so that an alternative preface could perhaps be written.

Footnotes

-

Although the Louvre had been collecting Islamic art since the 1830s and a ‘Muslim art’ section was created in 1893, before the construction of the new wing, these artefacts were not displayed in a designated department, but scattered across several others such as the Department of Decorative Arts, the Department of Asian Arts and the Department of Near Eastern Antiquities. The construction of the new wing was largely funded through a $20 million donation by Saudi prince Alwaleed bin Talal in 2005.

-

The installation was significantly exhibited in the Salle de la Maquette at whose entrance visitors find a large-scale model of the present-day Louvre, revealing different stages in the construction of the palace.

-

Preface to the First Edition was on show from 19 January to 8 April 2013. For the previous two years, between 2010 and 2012, Raad had been an artist in residence at the Louvre.

-

Jacques Derrida, Dissemination (trans. Barbara Johnson), London: Athlone Press, 1981, p.9.

-

Gérard Genette, Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (trans. Jane E. Lewin), Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp.1–2.

-

This tendency can be seen as an extension of the institutionalisation of institutional critique. While the intellectual and artistic value of such critical practices is not negated by their existence within the institution, clearly their practical function is neutralised. If, by raising questions and prefiguring alternative scenarios, these practices have the potential to reshape institutional spaces, they are also prone to be instrumentally used as a convenient stand-in for more radical steps that the institution is unwilling to take.

-

This reading of Raad’s preface is indebted to and largely based on Wendy M. K. Shaw’s keynote speech as part of the conference ‘Troubled Contemporary Arts Practices in the Middle East: Post-colonial Conflicts, Pedagogies of Art History, and Precarious Artistic Mobilization’ at the University of Nicosia, organised in partnership with the Birkbeck, University of London, 3–4 June 2016.

-

I take the idea of ‘colonial knowledge gathering’ from Priyamvada Gopal, ‘On Decolonisation and the University’, Textual Practice, vol.25, no.6, 2021, pp. 5–6.

-

I take from Raad the use of the adverbial phrase ‘in the Arab world’, rather than the adjectival ‘Arab’, as it accounts for a more inclusive understanding of art produced in an ethnically diverse and far from monolithic region (although perhaps Arabic-speaking would be more accurate). While this locution allows Raad to focus on local sociopolitical conditions and their specific intersection with processes of globalisation, his use of the term also presents an unmistakable mockery of the growing popularity of the regional show as a format to curate non-Western art, especially in Western institutions.

-

These includes cultural institutions, independent art organisations, commercial galleries, art fairs, museums, foundations, school programmes, workshops, art festivals, funds, residency programmes, prizes and journals, which have emerged in cities as diverse as Abu Dhabi, Alexandria, Amman, Algiers, Beirut, Cairo, Doha, Dubai, Istanbul, Jerusalem, Manama, Marrakech, Ramallah, Sharjah and Tangiers.

-

On the artist’s website, The Atlas Group is described as ‘a project undertaken by Walid Raad between 1989 and 2004 to research and document the contemporary history of Lebanon, with particular emphasis on the Lebanese wars of 1975 to 1990. Raad found and produced audio, visual and literary documents that shed light on this history. The documents were preserved in The Atlas Group Archive with a selection available on this site.’ See https://www.theatlasgroup1989.org/ (last accessed on 27 April 2022). While such presentation makes clearer the artistic nature of the project, which was mystified in its earlier manifestations, factual discrepancies remain, such as for instance the dating of the project. While Raad started working on The Atlas Group in the late 1990s, often the files/artworks that constitute the project bear a double date: one being the attributed date, and the other being the date when Raad produced the work.

-

For the scripts of Raad’s gallery tour, see Walid Raad, ‘Walkthrough, Part I’, eflux Journal, no.48, October 2013, available at https://www.e-flux.com/journal/48/60038/walkthrough-part-i/ and W. Raad, ‘Walkthrough, Part II’, eflux Journal, no.49, November 2013, available at https://www.e-flux.com/journal/49/60016/walkthrough-part-ii/ (last accessed on 25 March 2022).

-

J. Derrida, Dissemination, op. cit., p.17.

-

Finbarr Barry Flood, ‘From Prophet to Postmodernism? New World Orders and the End of Islamic Art’, in, Elizabeth Mansfield (ed.), Making Art History: A Changing Discipline and its Institutions, London: Routledge, 2007, pp.44–45. See also Chad Elias, ‘The Museum Past the Surpassing Disaster: Walid Raad’s Projective Futures’, in Anthony Downey (ed.), Dissonant Archives: Contemporary Visual Culture and Contested Narratives in the Middle East, London: I.B. Tauris, 2015, pp.215–31.

-

In his study of classical anthropology, Fabian defines the ‘denial of coevalness’ as the ‘persistent and systematic tendency to place the referent(s) of anthropology in a time other than the present of the producer of anthropological discourse’. This tendency is evident also in the framework of other disciplines studying non-European cultures, including art history. Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Objects, New York: Columbia University Press, 1983, p.31.

-

This temporal dissociation has in fact served to reinforce narratives of a supposed decline and decadence of the Islamic artistic tradition. In this articulation, the development of a local modern art has been seen as disjunct from local heritage, even when it explicitly references and reworks indigenous forms and motifs in an open and experimental relationship with both local tradition and transnational modernism. As a retort to such academic proclivity, rooted in imperial and orientalist dispositions, art historian Iftikhar Dadi has proposed a study of ‘modern’ and ‘contemporary’ Islamic art in Iftikhar Dadi, Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

-

Negar Azimi, ‘Trading Places’, Artforum, vol.46, no.8, April 2008, p.394.

-

Such position is espoused, for instance, in Walter D. Mignolo, ‘Enacting the Archives, Decentering the Muses: The Museum of Islamic Art in Doha and the Asian Civilizations Museum in Singapore’, Ibraaz, no.6, 6 November 2013, available at https://www.ibraaz.org/essays/77 (last accessed on 26 March 2022). However, Mignolo’s idea of delinking is based on what I see as a problematic decoupling of westernisation (or Western hegemony) and capitalism.

-

Hanan Toukan, ‘The Palestinian Museum’, Radical Philosophy, vol.2, no.3, December 2018, p.19.

-

As a counterpoint to the globally integrated and capital-driven museum format emerging in the Gulf, Toukan opposes a model of smaller ‘postcolonial’ museums, like the Palestinian Museum in Ramallah. While their finances are not completely disconnected from the Gulf, these museums are laboratories for a different form of ‘decoloniality’: one that is not content with a simple ‘decentring of the art market and the flow of art sales’, but that contends with ‘a forestalling of the violence of amnesia and narrative erasure that accompanies colonialism’. Ibid., p.20.

-

The narrative caption to Preface to the Third Edition (activated verbally in Raad’s performative gallery tours) speculates that the objects’ transformations will appear only immaterially and psychologically ‘in the dreams and psychological disorders of non citizens working in the Emirate’ – a coded hint to the exploitation of migrant workers in the construction of museums. Raad is also a member of the Gulf Labour Coalition, an activist group composed of international artists, writers and scholars, that since 2011 has denounced the systemic abuse and discrimination of migrant workers in the region.

-

This is not, to be clear, an argument against restitution based on the pretext of ‘lack of specific provenance’ – an argument which has been compellingly debunked by Chika Okeke-Agulu among others. It is rather a caution against mistaking an inversion in the direction of travel of artworks for a genuine return, failing to consider ‘inequities of the patronage power relation’ and broader geopolitical schemes. See, for instance, Anneka Lenssen and Sarah A. Rogers, ‘Articulating the Contemporary’, in F. B. Flood and Gülru Necipoğlu (ed.), A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2017, p.1333.

-

F. B. Flood, ‘Staging Traces of Histories Not Easily Disavowed’, in Walid Raad (exh. cat.), New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2015, p.174.

-

Jalal Toufic, The Withdrawal of Tradition past a Surpassing Disaster, Beirut: Forthcoming Books, 2009, p.29.

-

Ibid., p.64

-

Walter Benjamin, ‘On the Concept of History’, in Selected Writings, Vol. 4, 1938–1940 (ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings), Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002, pp.391–92.

-

Ann Laura Stoler, Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times, Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2016, p.7. One of Stoler’s examples are the environmental effects of colonial agrobusinesses that while persisting in the present are ‘sharply cut off from the history of imperial mandates that set them on their damaging course’.

-

Ibid., p.10.

-

Ibid., p.15.

-

I. Dadi, Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia, op. cit., p.13.

-

For Nada Shabout, the abstract school of modern Arab art ‘alternate[s] between a geometric pattern inherited from a traditional Islamic design and a cursive characteristic of Arabic script’. N. Shabout, Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics, Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2015. For a consideration of the twentieth-century valorisation of Islamic art as an art of abstraction, see Markus Brüderlin, Ornament and Abstraction: The Dialogue between Non-Western, Modern and Contemporary Art, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012.

-

Kobena Mercer (ed.), Discrepant Abstraction, London and Cambridge, MA: Institute of International Visual Arts and The MIT Press, 2006, p.7.

-

Jessica Winegar, Creative Reckonings: The Politics of Art and Culture in Contemporary Egypt, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2006, p.17.

-

Michel Foucault, ‘Nietzsche, Genealogy, History’, in Paul Rabinow (ed.) The Foucault Reader (trans. Catherine Porter), New York: Pantheon, 1984, p.78.

-

A. L. Stoler, Duress, op. cit., pp.23–24.