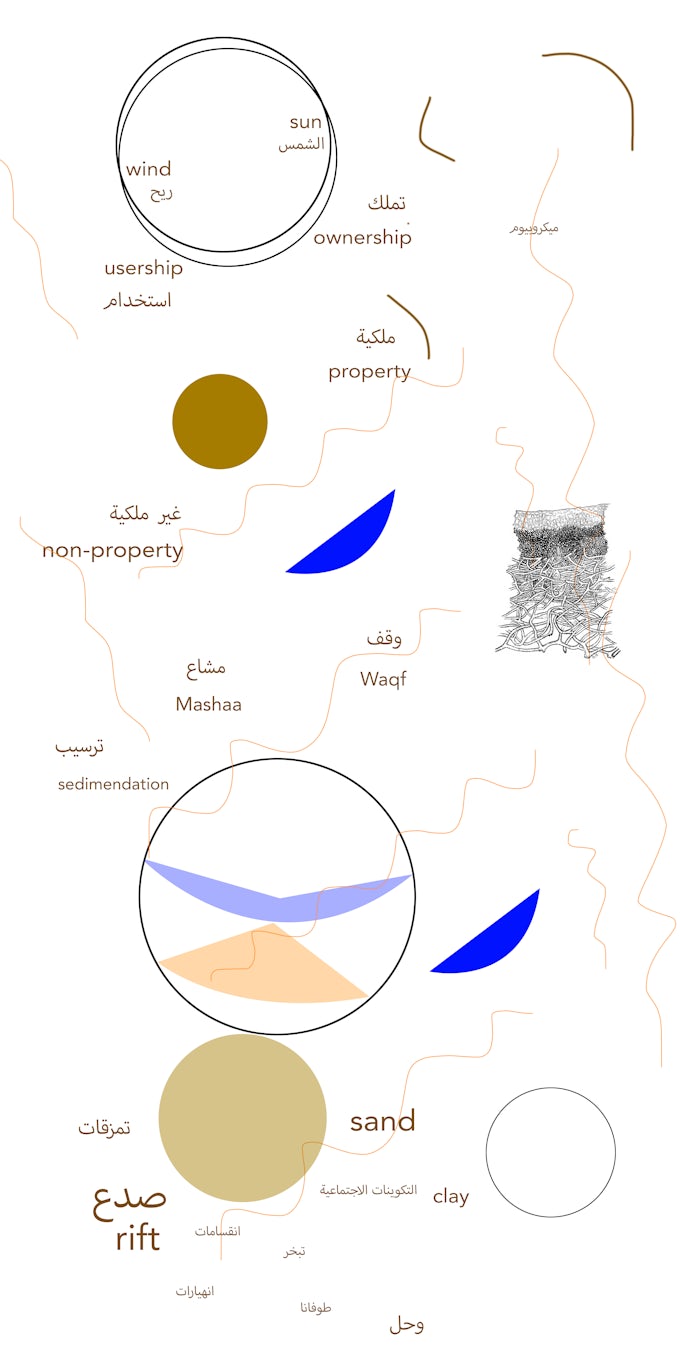

Melek means ‘property’ in Arabic. If the accents are shifted, it becomes Malak which means ‘king’. Or, with the extension of la (both phonetically and accent), it turns into Malaak, ‘angel’. Maalek, with the extension of Ma, is both the owner and the sovereign. If the owner is sovereign over the land, or if the act of owning makes him sovereign, then the angel, who hovers over the land either to protect or control it as god’s property, is the guardian of the land prior to its status as an owned object. Melek, Malak, Malaak, Maalek.

The etymology of the word Melek is a composition of several words. Ma laka, which could be literally translated into ‘What Yours’, hints to the omitted pronoun Houwa – Ma Houwa Laka, namely ‘What it is Yours (What is Yours)’. The omission of the pronoun that indicates one’s property is a necessary step to become a Maalek – an owner. The removal of the Houwa, which points to the specific object of possession, makes the owner sovereign over his possession. This necessary deletion makes Melek (property) possible, in language first, and hence in the very act of owning that inevitably erases another possibility: that of not owning or of non-property (Al la-molkiah). Erasure does not mean disappearance; one still hears the Houwa in the word Melek despite its obliteration. Houwa – or the pronoun that indicates the specific object that is owned – still echoes in the act of owning, just like the obliterated possibilities of non-ownership, continue to resonate despite their necessary erasure in order to make property possible. Every act of ownership performs a necessary erasure and also comes with the possibility of non-ownership. This does not mean that we simply hear the history of the commons (beyond ownership) whenever we are confronted with property. It rather means that this history, which is not the past, continues to exist in the current form of property.

In Islam the angel can turn into a human in order to communicate with the human world. It is older than humans and older than the jinn. Unlike angels, jinns live in a world of their own parallel to the humans’, but they can still intervene physically in the latter and cause harm. They can float, unseen, in the jinn’s atmospheric world, but they can also take the form of a human, a snake or a dog. To be possessed by a jinn means to be inhabited by it, which could lead to a ‘psychotic’ episode. Possession is a state of temporary ownership. It can also become permanent. One might be possessed for a lifetime. The Arabic translation for possessed is maskoun, ‘inhabited’. Which comes from sakan, meaning ‘habitation’. Sakina means ‘tranquillity’. The tranquillity of being inhabited by a jinn. Or mamsous, which means ‘touched’. Touched by another spirit. Haunted by it.

What is yours haunts you, and what is yours is haunted. It can never become fully yours. It is yours as much as it is the jinns’ and the angels’. It is possessed, inhabited. Your desire is to possess what is already possessed.

Ownership in a modern legal sense is haunted by the history of a different relationship to land: that of usership. For example, the category of the Mashaa’ that still exists in some regions of the Levant, is a system of communal land tenure that is truly beyond ownership. As an active legal category, it disturbs and often obstructs the naturalisation of private property.

Reverting Back to Mashaa’

The land is located in northern Lebanon, 400 metres above sea level. It was previously a quarry, but it is not used as such anymore. I have known it for a very long time as my father comes from a nearby village. It is divided between different owners. Its soil is extremely damaged due to years of quarrying, but rehabilitation is possible. Wael Yammine from SOILS Permaculture Association Lebanon tested the grounds and proposed a rehabilitation plan. The idea is to transform the land into a Mashaa’ that will be collectively managed by the families who live around it and who do not own any land. With lawyer Maya Dghaidi we have been exploring possibilities of transforming the land from its status as private property into a Mashaa’. With historian Wissam Saade we have delved into the history of private property in Mount Lebanon. By going back to the Ottoman Land Code (1858) we try to find ways to revert back to a relationship of usership, rather than one of ownership. The private property regime in Mount Lebanon was institutionalised in the 1920s during the French mandate. Given that, relatively speaking, this is not a long time ago, the possibility of non-ownership seems less of an impossibility. Non-property as an alternative relation to land is still within collective memory.

In absolute terms, everything was mashaa’ in the Ottoman Empire. But there was land that was worked, cultivated and land that was not cultivated. The lands that were cultivated would fall under fiscal renting, and therefore, later during the Tanzimat reforms, under the distribution of property and the struggle to dispose of the hereditary appropriation of the soil.

It is very important to see how the question of what goes beyond the property regime was treated, by thinking that before 1839 everything was in the absolute mashaa’ because everything belonged to God. In Islamic theology, the agricultural land belongs only to God and this is the very meaning of the Istikhlaf theory, that to Adam was entrusted the Earth. That the Earth belongs to God. But between this principle and the application of this principle there is a great paradox. This principle would become a justification for a system at the top of which we find the sultan and a hierarchy that functions with some semblance of a system of merits, military merits. To reward someone who has done great things in the Ottoman army, they were given a tax firm [a form of taxation and revenue collection]. In other cases, a tax firm was given to those who were deployed to crash rioters or rebels, or to defend rural areas against the Bedouins. The tensions between the sedentary, the semi-sedentary and the Bedouin would continue, up until the nineteenth century, to represent a major challenge in the Levant at the dawn of the modern nation-state formation.01

An Image Inside an Image

The material reality of land, its topography and topology, cannot be inscribed into a legal system in its totality. What is left outside the possibility of inscription is what renders the land’s relationship to law incomplete. It is this very gap between what is written in law and the materiality of the land’s components – whether bacteria or other soil constituents – that renders the question of property transformable and changeable. In this gap the question of inheritance and transmission acquires complexity.

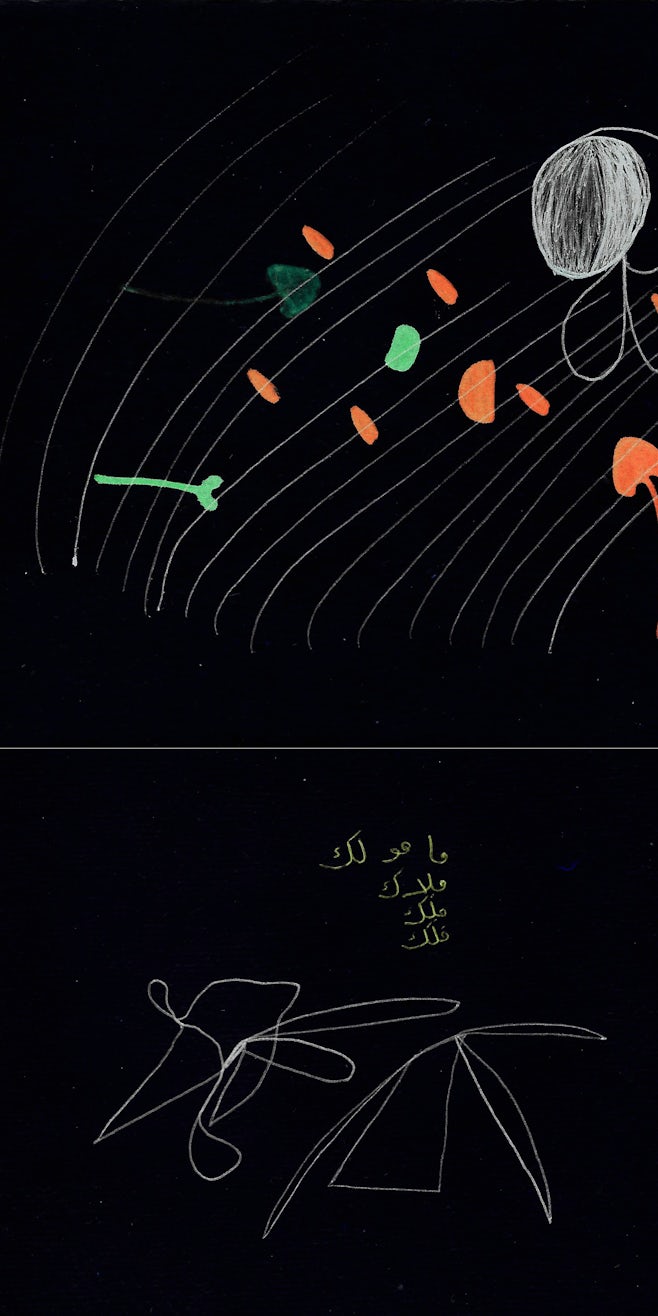

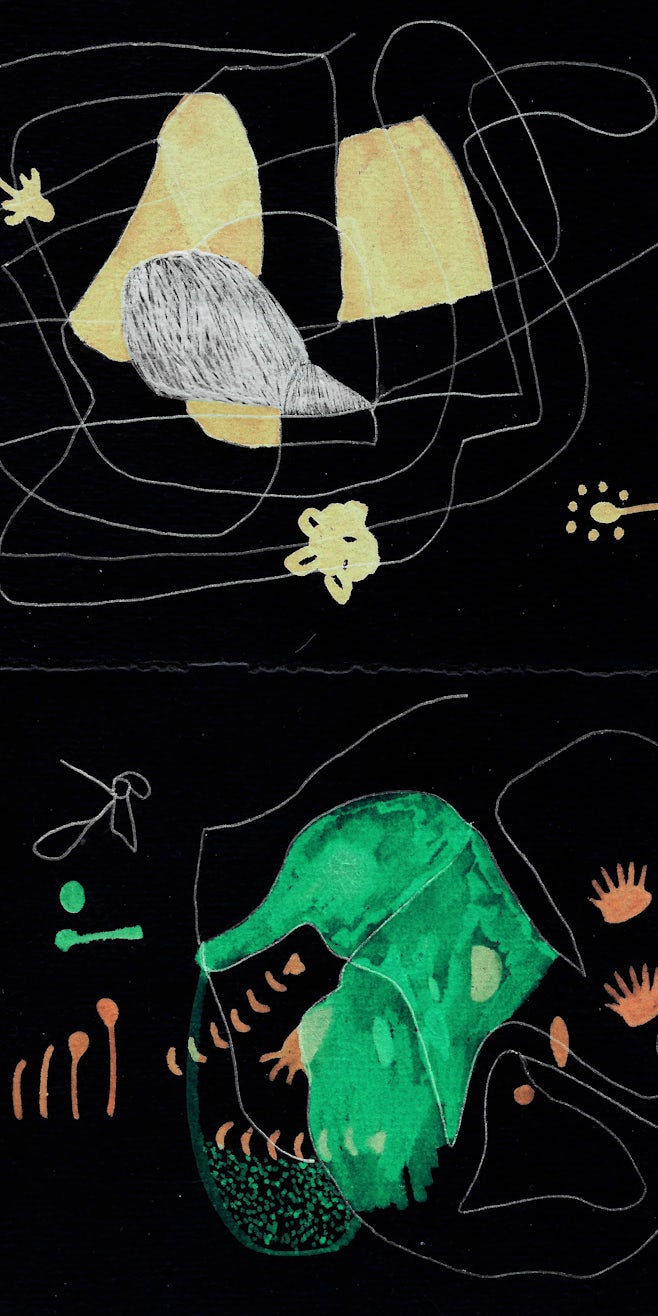

The filmic – like the legal, the agricultural, the historical, the geological as well as other forms of knowledge – could potentially contribute to a shift towards non-property. When we dig this relation of non-property out of the landscape, we start to perceive the land differently. We start to produce a new image of it. The question becomes: how can we film land without reproducing an imaginary of property and ownership? One of the purposes of this type of film-making would be to take the land out of its colonial representation as terra nullius, which has historically served to justify expansionist and extractivist mechanisms. It would be to shift the relation towards one of non-property by de-commodifying the land. To that end, the image of a land needs to be taken out of its landscape-form and turned into a quasi-scientific image: one that looks microscopically into the living matter that negates property. A macro image inside the landscape that negates the landscape. To create that macro image, one needs not only other forms of knowledge and new modalities of viewing, but an understanding of the negative as well. The filmic negative is what appears in the dark room during the development process. The negative from which the image appears, but also that which makes sight and appearance possible. The negative in the case of the land is the very life that negates property. Without fetishising it, one can look at that invisible life as a possibility for the refusal of terra nullius. It incarnates this very refusal. The positive, in this case, becomes the landscape, the commodity, the objectified land. And the negative whatever is not seen but allows sight. So perhaps that unseen image inside the visible image is what we will need in the process of deconstructing the ‘empty’ landscape. Without rendering it visible, we will need to insist on the invisible that haunts the landscape – from the bacterial to the human remains to what was written out from it for the purpose of colonial expansion.

Dreams: The Transmission of Defeat – a Counter-Image

In recent years I have been having recurrent dreams in which my father appears with a politician, speaks about politics or maintains a heavy silence when I ask him about a political situation that would possibly affect our future. Once I dreamt him telling me: ‘Nasserist politics only materialises itself in its ceremonial performance, and do not mean anything outside of it’. In the dream this was said at a wedding ceremony that was attended by some Lebanese politicians. It seemed as if my father was trying to tell me that the wedding is not the relationship itself, but rather a mere performance similar to Nasserist state politics: that is, empty speech.

In my dreams, my father has appeared with Nasser, Hariri and many other politicians – sometimes criticising them, other times complicit. But his comment about Nasser’s politics has also a different meaning. It implicates the downfall of an optimist postcolonial moment that was concurrent with the modernist project of nation-state building across the majority Arabic speaking world. It also expresses his scepticism around the performance of political speech, state politics and the father-state. In the dream, father and father-state are in conflict, but also confused with one another. It was as if my father was trying to save himself from the father-state by transmitting his defeat and making it my inheritance. My defeat. But what to do with it?

I suppose that the image of non-property that I was trying to produce is one of resistance despite the inherited defeat, a resistance to the image that is transmitted to me in the dream. There are histories, struggles and defeats that we inherit and there are others that we choose to inherit. But how do we inherit them? How do we carry and propagate them in the world with our own tools?

Learning from Pelshin

There is a history of partisanship and militancy in the arts, film and culture more generally. An anti-colonial history that has produced a culture of resistance and was in turn imagined and produced by it. The embeddedness of culture in political struggle was and continues to be an essential component that shapes the imaginary of that struggle. An imaginary that travels around the world and finds a home in other struggles and is, in turn, influenced by them. Internationalism also always denotes an internationalist alliance of political imaginaries coming together and building fronts. These alliances are essential to project a counter-image to colonial-capitalist visions onto the world.

The word ‘vision’ directly refers to sight. Today the question might be how to see and make things be seen without imposing one’s vision? How to be in solidarity without exposing, overexposing or underexposing the groups and people we are in solidarity with? In a world where the myth of art’s autonomy is still propagated by the art market and art institutions, how can we be again embedded (as artists, cultural workers and institutions) in visions that explode capitalist imaginaries? How do we contribute to these visions? Through images, structures, organisations, for example?

In reality this is a question of solidarity, and one is in solidarity because one knows how closely entangled our lives are. It becomes the only way to survive in the world. In a letter to internationalist activists Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt, Karl Marx described how English workers need to understand that their survival is linked to that of the Irish working class. This interdependency is key to understanding solidarity. But it also helps us to comprehend the fragility of solidarity and the relations it gives raise to, as the world moves and changes. How to maintain them? And how to preserve their complexity? There are friendships born out of solidarities that last for a lifetime, which reminds us that the intimacy of those friendships is what constitutes solidarity in a feminist manner. A feminist understanding of solidarity is also about building friendships, political friendships that entail both togetherness in fight and intimacy. Which makes these ties more complex, richer, and sometimes more difficult.

My relationship with some friends from the Kurdish autonomous women’s movement can be described as such. The encounter with their singular worlds has affected mine forever, on many levels. And this is what I understand by solidarity. Solidarity is when you are changed politically, intellectually and emotionally by certain encounters. You find yourself in solidarity because you cannot be otherwise. It is not a flat monodirectional political stance, but a political stance that is a multidimensional relation. We stand in solidarity because, in different ways and different scales, we share a loss, a defeat, an oppression that pushes us to build a shared political horizon towards which we struggle. Sometimes it is political loss and defeat that drive the search for and the formation of new alliances, new political relations and a new political horizon.

After the so-called Arab Spring in 2011, the feminist movement and discourse grew ever stronger in many countries in the region. While fighting against certain liberal feminist ideologies, we were interpellated by the Kurdish municipal victories in Bakur (Turkey) and the self-governed region in the North of Syria. In Lebanon, this combined with a feeling of paralysis in local politics and worry about the growth of reactionary politics across the region after 2013–14. During the trash protests in 2015, a feminist coalition formed that started to think about the necessity of an intersection between ecology and feminism. The Kurdish autonomous women’s movement presented us with a practical example of this intersection. It became necessary for us to learn from it.

The interpellation by the Kurdish autonomous women’s movement offered also a response to the question of what to do with our inherited defeats. What to do with the current state of affairs, especially in the Levant region where we are surrounded by collapsed regimes, whether autocratic-dictatorial criminal regimes like in Syria, oligarchic and differently criminal regimes like in Lebanon, or a settler colony in Palestine.

In 2016 I invited Dilar Dirik and Meral Çiçek to present the work of the Kurdish autonomous women’s movement and its structural and infrastructural organisation in Beirut at 98weeks, a small research project I was co-running. We convened around a text by guerrilla fighter, writer and ideologue Pelshin Tolhildan that Dirik and Çiçek had translated from Turkish to English. It is titled ‘Ecological Catastrophe. Nature Talks Back’. Pelshin writes from her experience as a guerrilla fighter in the Qandil Mountains in Iraqi Kurdistan/South Kurdistan, where she spent a lot of her time and life. She talks about the question of self-defence inherent to nature and the way it is entangled with the land she is fighting for. She also writes about the contradiction of war and ecology that is at the centre of the guerrilla fighters’ life in the mountains. Pelshin develops an ecological philosophy emerging out of her life as a guerrilla fighter and based on the intersection of social ecology and feminist politics. I sensed from our conversation that her intimate knowledge of the land and the landscape, of its fauna and flora and the possibility of its transmission is what drives her fight. It’s as if Pelshin wants to transmit this knowledge and the land itself, but not through the system of property inheritance. On the contrary, she insists on the transmission of her very relationship to the land, that is one of usership and not ownership. Pelshin’s thoughts and writings were the answer many of us had long been looking for. Her life, praxis and writings presented a new way of thinking the anti-colonial, ecological and feminist struggle.

Pelshin was a major inspiration for the beginning of a long search to come. Her writings haunt my thoughts and work, particularly the four-part film series Who is Afraid of Ideology? (2017–22). In Part I, for instance, my position as a film-maker becomes that of a transmitter of her thoughts on social ecology. I become a listener, and the film becomes the vessel for our conversation and its transmission. Pelshin talks about ecology as a set of relations that are inherently linked to each other. At the same time, we (the filmic device and I) become the transmitters of the relationality of struggle itself. The transmitters of an ecology of struggles, which are inherently and intimately connected. We witness this transmission through Pelshin’s writings, through her stories.

How can one be in solidarity and in conversation with other struggles knowing that we are neither separated from these struggles nor fully embedded in them? For me, film became a space for rethinking collectivity, knowledge sharing and production through reading groups, workshops and conversation. It also became a tool to look closer and zoom into entities such as bacteria, soil, seeds. A tool for forging new alliances with non-human species that are an inherent, although often overlooked, part of the collective. Questions of how to film land, soil, seeds, and the ethics and politics of images slowly unfolded while I found myself in the midst of the process. I used many lenses as research tools to look and hear through. These devices allowed seeing and sometimes resisted the possibility of seeing or framing the land. Through them, a topology, topography and ecology of film-making can be developed. One that is embedded in an imagination for a different kind of transmission. Embedded in an image, perhaps, of non-ownership.

Footnotes

-

Edited excerpt of an unpublished interview with Wissam Saade, January 2022.