What is a gallery? A site, a context, a situation. Imbricated in the history of art are diverse facilitating institutions, and the commercial gallery is a contributor often left out of analysis. As a site of simultaneous production and exchange, galleries may constitute a physical framework for the ‘socius’ of art, while gallerists’ individual strategies of support, advocacy, sale and distribution (as well as, of course, speculation and exploitation) inevitably shapes art in both overt and indirect ways. Yet, with only a few exceptions,01 the significance of the operations of galleries and the ‘work’ of gallerists are, beyond biography, rarely accounted for in the discipline of art and even exhibition history. By tracing two of the most remarkable US gallerists of their time – Pat Hearn and Colin de Land – the exhibition ‘The Conditions of Being Art: Pat Hearn Gallery & American Fine Arts, Co. (1983–2004)’ at the Hessel Museum of Art in Annandale-on-Hudson sets out to do just that, presenting the gallery as one of art’s sites from which one can and must write a history of art – a history that is at once formal, social and interpersonal.

Unknown to some, near-cult characters to others, Hearn and de Land were central actors in New York’s art world from the early 1980s to the early 2000s, initially as distinct agents but increasingly overlapping as their social, professional and romantic lives interweaved through the 1990s. (Both passed away prematurely as a result of cancer, Hearn in 2000, de Land in 2003). While both partook in multiple exhibition platforms in and outside of New York, the exhibition (curated by Lia Gangitano, Jeannine Tang and Ann Butler) focuses on each of their (more-or-less namesake) commercial galleries, whose libraries and archives have been housed and expanded upon at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College and the Hessel Museum since 2012. 02 An avid participant in Boston’s punk-driven art and music scene of the late 1970s, Hearn relocated to New York and launched her pristine floor-tiled gallery on the corner of Avenue B and East Sixth Street in 1983 with a series of ‘New Painting’ shows. De Land, meanwhile, launched the sesquipedalian ‘American Fine Arts, Co. – Colin de Land Fine Art’ on East Sixth Street in 1986, showing the work of Richard Prince, Peter Nagy and ‘J. St. Bernard’, one of several pseudonyms under which he would produce art throughout his career. Distinctly, both displayed a fascination for performatively enacting and speculating the ‘gallery’ as a stage and situation within the cultural milieu of a booming cultural metropolis – Hearn through a polished, Mary Boone-esque persona, de Land as an underground impresario – and both with an exceptional understanding of art’s social, political and economic development in their time.

In a scattered chronology, the exhibition traces many of the solo presentations and curated exhibitions facilitated by the two galleries. Between the presentation of now recognised artists’ earliest work – including that of Simon Leung, Joan Jonas, Jessica Stockholder, Mark Dion and Jutta Koether – important historical recoveries appear too, for example in the case of Kembra Pfahler (whose name is mostly known in the underground film and music world), the institutional critical artist Lincoln Tobier 03 and Tishan Hsu. A contemporary of New York’s 1980s ‘neo-geo’ trend (‘neo-geometric conceptualism’), Hsu’s wall- and floor-based objects (aHead, 1984 and Institutional Body, 1986) are abundant with bodily orifices, but also what appears as interior fixtures, the soft curves of stationary computer screens and warped cybernetic grids. As part-bodies, part-machines, they procure an eerie corporeality radically different from the polished, simulated surfaces of many of his contemporaries at PHG, such as Peter Schuyff and Philip Taaffe, whose work surrounds Hsu’s in the exhibition’s central gallery.

Accompanying many of the works and re-staged installations at the Hessel is carefully presented archival documentation, where promotional material, correspondence and ephemera runs alongside photographs of gallery installs, Christmas parties, art fairs, openings and vacations. In this way, the exhibition sheds a light on the labour of production, mediation and advocacy that lies behind any work of art, particularly as it circulates (or attempts to do so) in a market – but also on the social life that inevitably informs this kind of labour. The curatorial vision is, as a result, purposely messy, leveraging a variety of museological techniques (archival, biographical, formal, contextual) to pose a question back to the audience: how do we ‘remember’ art and its world(s)?

At times the exhibition falls back on well-established art historical themes or tropes, categorising along identitarian lines such as gender or sexuality. For instance, the sexually explicit black-and-white photographs of Jimmy De Sana, a long-time friend and collaborator of Hearn, are presented alongside the post-minimalist installations of Tom Burr, who developed his approach to queer urban archaeology while at AFA. While evoking the iconography of S/M, De Sana’s images feel self-consciously outside any real discourse of sexual practice, concerned instead with presenting the human body as one object amongst others; on the other hand, Burr’s From 42nd Street Structures (1995) and Movie Theater Seat in a Box (1997) specifically address gay cruising practices by way of its architectural remnants, the body notably absent, echoing the rapid disappearance of these spaces in a changing New York City. If the exhibition’s foregrounding of singular works is sometimes compressed, the accompanying catalogue expands on the social thematics of the show with ten newly commissioned texts by an intergenerational group of art historians and curators, as well as an exhaustive (and very useful) exhibition chronology. In their respective essays Mason Leaver Yap, Jeannine Tang and Diedrich Diederichsen all tackle the ways in which the formation of cultural ‘scenes’ happens alongside processes of gentrification (Hearn was the very first commercial gallery, following the non-profit Dia, to move to the run-down Chelsea neighbourhood in 1994); and in a highly personal text, Gangitano solidifies Hearn as a ferocious supporter of queer artists, taking on responsibility for multiple artists’ estates as the AIDS crisis continued to take its toll.

What comes across strongly from both exhibition and catalogue is the fact that art history always unfolds at the interface between personal lives, social scenes, markets and institutions; what artist Renée Green has referred to as ‘contact zones’, ‘where cultures meet, clash and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power.’ 04 For her 1994 exhibition ‘Taste Venue’ at Pat Hearn Gallery, partially re-staged at the Hessel, Green recast the gallery as the generically named ‘Venue’, a ‘cheap trendy space in a hip downtown location’, advertised in newspapers such as The Village Voice as a space for rent by anyone interested. 05 Over the span of the month, a range of cultural and commercial events unfolded there, marking art’s overlapping with other cultural scenes in New York’s hip downtown milieu. Whether by actively stylising the presentational modalities of a commercial gallery, 06 or by showing art ‘about’ art and its spaces of contact and exchange, it is indeed the concern for the gallery as a sitethat emerges as the most persuasive characteristic across the projects initiated or supported by Hearn and de Land. Julia Scher’s security systems, for example, exhibited and installed at both PHG and AFA, reflected on the ambivalent, paranoid pleasure of knowingly being surveilled; 07 and Andrea Fraser explored the choreographed protocols of the gallery space through performance works at AFA such as May I Help You? (1991), which saw three performers – known as ‘The Staff’ – promptly commencing dense, theory-driven sales pitches of Allan McCollum’s minimalist paintings. Distinct from both classical institutional critique and relational aesthetics, the gallery is here neither antagonised nor idealised so much as it is subject to a form of discursive ‘site analysis’ in which all agents – the artist and gallerist in particular – are subject to interrogation. 08 By being re-cast or read alongside other cultural spaces (cruising grounds to poker clubs, prisons and natural history museums), we approach through the exhibition an analysis of the gallery as a central platform of modern society, characterised by shifting modes of cultural consumption, work, sociality and critique.

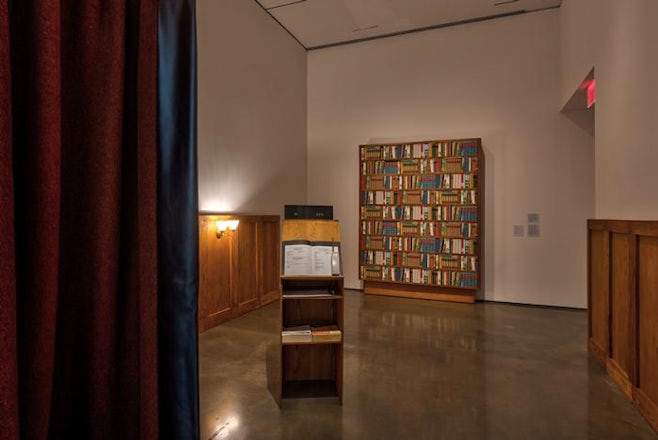

The fact that many of these in situ works are still to be properly examined by art history is perhaps due to their limited presence in present-day exhibitions, hard as they were to collect and maintain, and, as a result, re-install or re-stage. The exhibition responds to this through a variety of museological tactics: Scher’s Hidden Camera/Architectural Vagina is recreated (presumably, non-functionally) in the gallery’s entry gallery, Fraser’s performance is presented through a single-channel video, while Green’s Taste Venue is re-presented as a reduced installation on one wall, facing (rather iconoclastically) a series of melancholic oil paintings by Pat de Groot (the last solo exhibition staged at Pat Hearn). An entire room is devoted to ‘works from’ (i.e. not the entire work) Christian Philipp Müller’s exhibition-artwork A Sense of Friendliness, Mellowness, and Permanence (1992), including a ‘gallery menu’ of AFA’s achievements, artists and prices and a bookstand stocked with his own exhibition catalogues (reducing his practice to one of didactic, self-exoticised promotion). Stockholder’s early total-installation at AFA is represented through a single architectural object (Untitled, 1989) in a room of other individual works of art by many artists; while the 1993 occupation of PHG by the experimental Cologne-art space Friesenwall 120 (organised by Stephan Dillemuth and Josef Strau) is rendered through traditional archival vitrines. In grappling with such a large variety of installations (all, presumably, with different involvement from the artists), the exhibition inevitably conveys an uncertainty about the museological importance of the ‘stuff’ of exhibitions: is it enough to resurrect the scenography but not the show itself?

It is also by its focus on the life around a gallery that the exhibition conveys some of its most vivid histories. Most pertinently, Lutz Bacher’s Closed Circuit sits as a haunting but poetic portrait of Hearn’s last year as she underwent cancer treatment. In 1997, the artist installed a CCTV camera over Hearn’s desk, with the live-feed displayed in the hallway of the gallery. In the 40-minute montage included in the present exhibition, we see Hearn writing, talking, reading and speaking on the phone before the slowly accelerating footage begins to bleach out entirely due to the accidental repositioning of a desk lamp. After Hearn’s death in 2000, de Land continued for a while to run her gallery by merging it with his own under the moniker ‘American Fine Arts, Co. – Colin de Land Fine Art at PHAG, Inc.’ Ever the corporate simulator, de Land extended Hearn’s stoic professionalism beyond her death, continuing to support her artists and increasingly fusing their critical trajectories.

While romanticisation is an ever-present risk in articulating such histories through the lens of the personal, from the point of view of today it is the idiosyncratic operations of Hearn and de Land – not the cult of their personalities – that qualify as the material for the writing of art and exhibition near-histories. Balancing finely between these, ‘The Conditions of Being Art’ is a contribution to an understanding of, as Green articulated in her press release for ‘Taste Venue’, ‘the function of the gallery … what it has been, fissures in that structure and what it can become’ 09 – as well as a bold exploration of how one might remember such a function in the space of a museum.

‘The Conditions of Being Art: Pat Hearn Gallery & American Fine Arts, Co. (1983–2004)’, is on display at the Hessel Museum of Art until 14 December 2018.

Footnotes

-

I am thinking, for example, about the remarkable book on Seth Siegelaub by Alexander Alberro (Conceptual Art and the Politics of Publicity, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2003) and, equally remarkable while offering a broader context, Sophie Richards’s Unconcealed, The International Network of Conceptual Artists, 1967–77: Dealers, Exhibitions and Public Collections (London: Ridinghouse, 2009). More recent is Francine Prose’s biography of Peggy Guggenheim (Peggy Guggenheim: The Shock of the Modern, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015).

-

See Ann E. Butler, ‘History Remains’, in Lia Gangitano, Jeannine Tang and Ann Butler (ed.), The Conditions of Being Art: Pat Hearn Gallery & American Fine Arts, Co., New York: Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College and Dancing Foxes Press, 2018, pp.259–69.

-

His 1993 exhibition ‘Cop Sculpture’, in collaboration with Ted Byfield, unfolded across both AFA and Pat Hearn Gallery. See Jennifer King, ‘The Image Makers on Wooster Street’, in L. Gangitano, J. Tang and A. Butler (ed.), The Conditions of Being Art, op. cit., pp.141–55.

-

Green had since 1991 been developing Pratt’s theories of cultural hybridity as a critical methodological paradigm for working, when a residency in Lisbon had led her to travel to Ceuta in Morocco to map the colonial traces of Portugal’s former empire. In Green’s work, however, the contact zone exceeds the strictly racial to encompass a multiplicity of encounters between cultural languages, sub-cultures, social classes and disciplines, and their implicit hierarchies of power (economic, social, aesthetic). Her ongoing thinking in around the potentialities of the contact zone manifested in the staging of a large symposium ‘Negotiations in the Contact Zone’ at the Drawing Center in New York, which coincided with the closing of ‘Taste Venue’ in April 1994.

-

Cited in Gangitano, ‘We Dream’, in L. Gangitano, J. Tang and A. Butler (ed.), The Conditions of Being Art, op. cit., p.177.

-

For Mark Morrisroe’s posthumous retrospective exhibition of sexually explicit photography, Hearn designed an elegant full-colour foldout brochure but presented it alongside an anarchistic double designed by Tabboo! – a cheap, single-sheet flyer daubed with photocopied images and thickly brished lettering announcing “it’s the MARK MORRISOE RETROSPECTIVE. PHOTOGRAPHS!” Similarly, the announcement card for Collins & Milazzo’s curated exhibition at AFA (October 1986) playfully emphasised the self-stylisation of the then-trendy curator duo.

-

Scher’s 1991 work I’ll be Gentle mounted a surveillance lens similar to those used by the FBI at the time, shrouded by a red frond, in the gallery stairwell; she would later set up an everyday video surveillance system at AFA across the street.

-

I borrow this term from James Meyer, who has outlined an approach to site-specificity that involves not only a material but a social, economic and ideological examination of art’s changing ‘place’ in society. See James Meyer, ‘The Functional Site; or, The Transformation of Site Specificity’, in Erike Suderburg (ed.), Space, Site, Intervention: Situating Installation Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), p.25. Notably, Meyer curated the group show ‘What Happened to Institutional Critique?’ at American Fine Arts in 1993, which drew together many of Hearn’s and de Land’s artists.

-

Renée Green, press release for ‘Taste Venue’, Colin de Land, American Fine Arts, Co., and Pat Hearn Gallery Archives, MSS.008, Series II.A, Box 101, Folder 1969, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College.