Two recently resurrected films from the fringes of early 1960s American independent cinema put forth stark black and white visions of a broken America sadly contemporary in its social divisiveness. Filmed in New York and Los Angeles, respectively, Shirley Clarke’s The Cool World(1964) and Kent Mackenzie’s The Exiles (1961) describe the complex of lamentable race relations, economic struggles and emotional tensions seething at the core of the country’s two major metropolises. Motivated by the protest culture that galvanized the civil rights struggle, and that moment’s call for moral responsibility in the face of social inequity, Clarke and Mackenzie–white filmmakers working on opposite coasts–embedded themselves within impoverished urban communities caught in the shadows of the American dream. Screened recently in Los Angeles, they are products of a past era’s youthful energy, which found new traction almost a half-century later in the highly politicized climate of the 2008 presidential election season.01The uncommon emphasis on public service, community involvement and political engagement that energized President-elect Obama’s winning campaign attests to a thirst for social action among the members of a new generation looking to pick up where the 1960s agenda of reform left off.

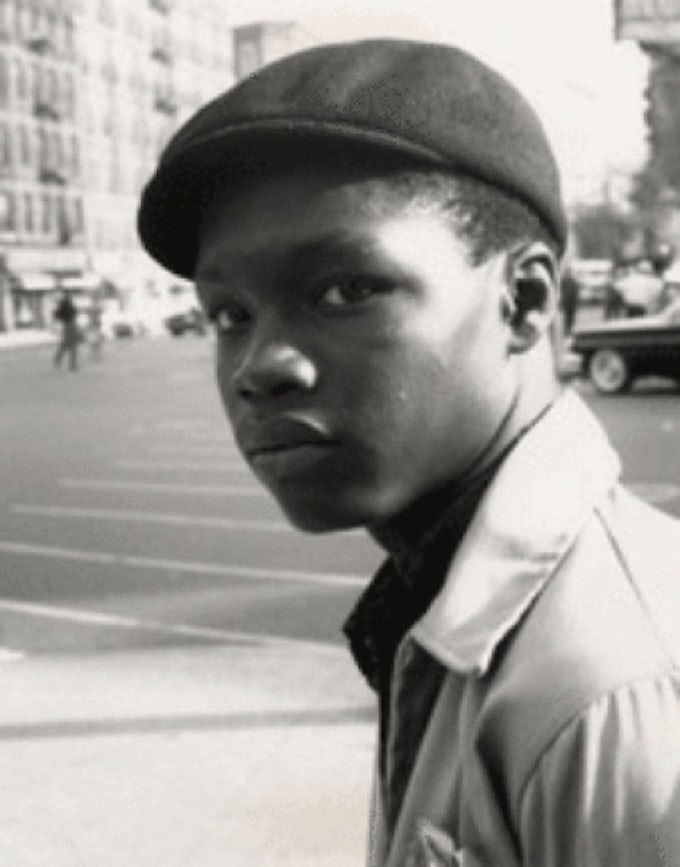

Characteristic of the social upheavals and culture wars that electrified the 1960s, a sense of rebellion is conveyed in each director’s stridently uncommercial choice of subject matter, confounding of filmic genre and rejection of conventional cinematic style. Clarke, a downtown dancer-turned-experimental filmmaker, worked with her then-boyfriend, Carl Lee (who also played the film’s main supporting villain), to adapt Warren Miller’s 1959 novel The Cool World into a screenplay of the same name. She used non-professional actors (mostly local kids living in Harlem) to play the character roles and shot everything on location on a shoestring budget. The film’s plot is minimal and elemental, boiling down to one troubled youth’s frustrated search for manhood. An ambitious 15-year-old boy named Duke struggles in the seedy underbelly of Harlem to acquire a gun, hoping to take over his gang, the Pythons, and redeem its slackening reputation on the streets. The script is acted naturally, affecting the gritty immediacy of Italian neorealism or French New Wave films like Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959) and Godard’s Band of Outsiders (1964). Stuffing his hands into his jacket pockets and pulling his hat down over his baby face, Duke fantasizes–in voiceover–about the respect he’ll command once he gets the piece: “People will say, ‘There goes Duke, he’s a real cold killer.’” Duke’s world isn’t cool; it’s cold, frigid and cruel. Urban pressures drive primal violence and animalistic antagonisms that are hinted at in the film’s images of stray dogs and cats wandering the streets contested by the Pythons and their rivals, the Wolves.

Shot three thousand miles west and three years earlier, Mackenzie’s film follows 12 hours in the lives of Native Americans living in the low-rent and long-since demolished downtown Los Angeles enclave of Bunker Hill. Mackenzie had been committed to the neighborhood since his first film, Bunker Hill – 1956. While still a student at the University of Southern California, he spent months getting to know the Native American community that made its home there, and witnessed its members’ self-imposed exile from the reservations devolve into dashed and doused dreams of big city life. If The Cool World is a documentary-style drama with a handheld feel, The Exiles flips the emphasis towards a pathos-filled, dramatic documentary employing improvisation and creative collaboration between cast and crew. Without a script or predetermined storyline, Mackenzie prioritized site-specificity, relying on a rough idea of the locations in which the film’s action would inevitably unfold. Of all those Mackenzie follows throughout this dusk-to-dawn journey, the young Apache Yvonne Williams, her negligent husband Homer Nish and the fun-loving ladies’ man Tommy Reynolds are the emotional and psychological anchors of the film’s aleatory, non-narrative drama. Romancing the city at night, Mackenzie combines film noir’s brooding mystique with the fetishized rawness and low-budget ethos of cinema verité, striking an affinity with early Cassavetes. Sustained internal monologues round out the principle players and tell of smothered hopes, exhaustion, despair, escapism and crushing frustrations. The non-professional actors play themselves, re-enacting scenes from their lives with an impressively unselfconscious camera presence and casual composure that speaks to a great degree of trust on set as well as to Mackenzie’s sensitivity as a director and documentarian. Centered on Homer and his posse–their barhopping and drunken car rides to nowhere–the film’s existential odyssey is in fact a typical night that repeats on loop throughout their lives, suspending them in bored malaise and Thunderbird-drinking, lotus-eating numbness.

Working in opposition to Hollywood conventions of the time, Clarke and Mackenzie navigated the continuum between documentary and drama to arrive at idiosyncratic amalgams adapted to their contexts, budgets and visions. Shooting on location, in Bunker Hill and in Harlem, had political ramifications–it was the documentary filmmaker’s equivalent of marching in the streets, occupying the social sphere and defining public space, with the camera’s presence signifying both affirmation and protest. The Cool World and The Exiles dramatize otherwise unrepresented experiences of what it was to be an American in the late 1950s and early 1960s, bearing witness to marginalized stories and embracing alternative strategies that defy industry norms. In The Cool World it’s Clarke’s rich documentary footage of Harlem’s street life, interspersed with the film’s more plot-driven scenes in an unadorned style, that steals the show. Seductively paired with a punchy jazz soundtrack by Mal Waldron (featuring Dizzy Gillespie among others) and punctuated, at times, by character voiceovers, the extended sequences of pedestrians and street corner activity do more to establish the film’s lasting appeal than the porous narrative’s concoction of drugs and gang warfare. A jolting and danceable rock ‘n’ roll soundtrack by The Revels plays a similarly essential role in The Exiles, activating mood and dramatizing Mackenzie’s protracted montages of downtown nightlife and bustling bar scenes at the Café Ritz. Scored to perfection, both films maneuver between diegetic and extradiegetic space, breaching cinematic illusion and formally demonstrating in sound what they achieve in their often seamless blurring of documentary and drama.

Mackenzie and Clarke exploit the social currency of documentary to play up the political nature of performance–the conflation of dramatic acting with real life converts the viewer’s identification with ‘character’ into a politicized investment in real people, communities and their stories. This is especially true in The Exiles, where untrained actors portray only themselves. Even though Mackenzie sought to avoid the romanticization of poverty and tried to portray his subjects evenhandedly, if poetically, his efforts remind us of the Heisenbergian conundrum of the documentary project, whereby the very introduction of a camera into a place alters (and thereby aestheticizes) the behavior of its inhabitants and the dynamics of their relationships. As Mackenzie’s camera scans the glittering surface of downtown Los Angeles’s nighttime streetscape, allowing the night to cut its own noir figure in inky shadows, it focuses with allegorical precision upon the Roxie’s marquee for Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life (1959), whose title phrase ultimately articulates the fascination on which both films hinge. Who is imitating life? Is it the actors as characters, or the characters who act “cool” while trapped in desperate existences? The difficulty with really good acting, both in art and in life, is that it ultimately risks not being recognized as acting at all; if the artifice is too convincing we take it for nature, and if one is “acting natural,” is it even acting any more? This issue of recognition defines performance as either authentic or artificial, informing our ability to distinguish between what is real and what is represented. Clarke and Mackenzie were fundamentally united in a formal interrogation of cinema’s representational conventions, a reflexive questioning that parallels a progressive political posture of doubt and vocal critique. Though resentment and bleakness haunt the margins and systemic failures shackle lives, Clarke and Mackenzie, in different ways, urge us to consider the possibility of an ideal community forming, momentarily and against odds, in the midst of marginality.

– Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer

Footnotes

-

The Cool World was screened by The Cinefamily at the Silent Movie Theater on July 18, 2008. Mackenzie’s The Exiles, which was recently restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archive, was screened at the Hammer Museum on 15 August 2008.