Nav Haq: I was reading how your work has been described in various exhibitions. The basis always tends to be around notions of language and communication. That’s correct, of course, but for me, there’s more complexity to it. I tried writing a basic description of your interests as an artist. What I came up with was that your work is about how to locate or invent forms of language across linguistic cultures and modes of cognition. But it’s interesting to hear from you – how do you describe the core of your practice?

Imogen Stidworthy: I work with different forms of language to engage with how communication happens and the forms of sense-making we rely on, consciously or unconsciously. Verbal language is so close to us; we reach for it but are constantly in conflict with it. I work with people who embody fundamentally different relationships with verbal language, because what I’m interested in is what flows around the verbal, different forms and registers of thought, and the realities they shape.

In recent years I’ve worked with people on the autistic spectrum who have no practice of language at all. This isn’t about what happens ‘in’ or to them, or me, or any particular person, but what happens between us in encounters between different forms of language. Like the meeting of tectonic plates, what is happening may be phenomenally slow and invisible to the human eye – or dramatic, even volcanic. What’s at stake is that it can give rise to different orders of communication and relationship, with others and self.

NH: The idea of sense-making is an interesting one. It would be good to hear about how you came to this subject in your work. I’m familiar with The Whisper Heard (2003) as an early example, but had you already begun this investigation before, in the 1990s?

IS: I studied sculpture at art school, where I made very material, abstract objects. Later I made large installations around London, in sites such as Tooting Bec Mental Unit, a huge 19th century asylum which was in the process of being shut down, but still had over a thousand patients. I tried to set up situations in which the visual appearance of the work was accompanied by

a strong self-awareness of the visitors’ own body in its relationship with the work, and a feeling of being unable to quite settle in or between them. These were ways of asking questions about different forms of language through the relationship between the materiality of an installation and its immaterial dimensions – between a wooden fence construction, more or less transparent screens, projected film, spatial relationships and empty spaces, and the images they evoked between them.

In 1992 I went to study at the Jan van Eyck Academy in Maastricht. It was a small geographical move, but a big one culturally. There was a sound and video studio where I was able to play with the voice as a material for the first time, recording and editing it, my own at first. It was quite a revelation to be able to work with such an ‘immaterial’ sculptural material and to be able to engage with ideas that I’d been working with through the physical installations, especially in terms of the relationship between the body and different forms of meaning embodied in elements of the work.

NH: So your exploration started with sculpture, and then you landed in this new linguistic context, which helped expand your thinking. Was the experience of living in another country, in another language, the trigger to your subsequent work?

IS: It contributed to it. One reason I wanted to leave the UK was a frustration with my own use of language in relation to my work, my inability to touch ‘the point’ of the work with apparently articulate language. In my upbringing and in the UK, even now, in general there has always been so much of a charge, assumptions and judgements around how we use language. It wasn’t until I went to the Jan van Eyck that I was able to see this more clearly in personal terms as well as theoretical ones, and how it had shaped my own language and values. Most people were speaking English as a second language, so familiar words were constantly being exposed in fresh, surprising ways and their meanings would suddenly emerge differently. The work I did with speech and recorded voice was part of an intense process of dismantling spoken language, my own and other people’s.

NH: And you worked with your father and mother?

IS: Luce lrigaray wrote ‘With your milk, Mother, I swallowed ice.’01 One of the first works I made in Holland was a sound piece, I \ The corners of the mouth (1993), which related to that feeling of being alienated from one’s home language at the same time as needing to create distance from, even expel it. It involved two sound recordings playing simultaneously, one was a recording of my mother’s voice made on a cheap cassette player, reading a poem by Anna Akhmatova in Russian, in her steady lilting rhythm – a classical way of reading poetry. The other was the sound of breathing, between being very gentle and something closer to retching.

The first work I made with my father was based on my experience of life modelling. As a life model you slip between being all mind and all body – an object whose lines and volumes are being continuously scrutinised. It’s very polarising. It was only when I put on my dressing gown during a break and it became a social situation, that I actually felt exposed. I wanted to work with this condition of slipping between one state and another – which the model experiences – and for the observer, a movement between objectifying the body on the level of the visual image, and being drawn into the mind and thoughts of that body through the voice. In To (1996), my father was in the position of the life model and I gunned him down with my electric typewriter – more of a violent silencing than a slipping. It was a staged situation but it wasn’t entirely under control – my father was often out of control in fact, and our family life was defined by unpredictable verbal violence. Losing control is essential to some degree for any staged situation to become interesting, and in this context, the tension between maintaining and losing control made it real.

Working with one parent and then the other and setting up situations in which certain dynamics could play out, I was asking questions around language and power through personal relationships. They didn’t remain in the personal because the work wasn’t about the person. They brought specificity to the work, which in earlier pieces was embodied in a physical site. It’s a funny comparison to make perhaps, but it’s about making relationships between individual and, to whatever extent, singular levels and wider structural levels.

NH: I know that your son also appeared in a later work, The Whisper Heard (2003). You describe the image of your father in To as a painting. I think there is a strong element of portraiture in many of your pieces. Works such as Sacha (2011–12) or Iris [A Fragment] (2018), for instance, are titled after the name of the person they revolve around. I would like to ask you about this mode of portraiture within your practice.02

IS: A portrait can bring you into a crux of something which is absolutely specific to the subject, and something that is shareable and recognisable for others. It’s the phenomenon of recognising something in the image that you hadn’t known you knew about yourself, or your own experience, which you hadn’t been able to see because it was too close to you, or too much of a given.

I met Iris Johansson after reading her book A Different Childhood (2014), in which she describes her experience of non-verbal being as a child. I spent time with her in Sweden and Egypt, where she lives and works for part of the year, filming and talking with her about her experiences and ideas about non-verbal dimensions of relationship, and the practices she’s developed to help people in various ways – she rejects the term ‘therapy’. She specialises in working with groups, as she says, working on the spaces between people, because ‘you cannot help anybody by working with them directly’. Iris is on the autistic spectrum and was non-verbal, or rather she had a non-linguistic relationship with language, until she was twelve. In her book she records very vividly how as a child her physical body would suddenly become immaterial – her word – and how she could see people’s thoughts, even if she couldn’t put words to them. Spending time with her, listening to her describing the process of learning to recognise herself as an ‘I’, allowed me to absorb her relationship with language also on an embodied level – this ‘atmosphere’ is what shaped my installation Iris [A Fragment]. I was learning about autism, including huge and ongoing changes, over time in how it’s been understood and treated, culturally and neurologically. The whole experience made me think in new ways about sense of self, the degree to which this is shaped by othering others, and how normativity plays out in relation to these questions.

NH: Your portrait of Iris shows also how she exists in constant negotiation within these normative structures. I understand this work is ongoing.

IS: When I finished the work with Iris, I felt there was more to develop. At that time, 2018, I had also been meeting Phoebe Caldwell regularly, a British therapist, now in her 80s, who is an authority in non-verbal communication, specialising in a method called Intensive Interaction, mainly with non-verbal people with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder). There’s a really compelling relationship between these two women. Iris embodies and talks about non-verbal being and autism from the inside, while Phoebe engages with both in her clinical and therapeutic practice of communicating with people with whom she doesn’t have a shared language.

I wanted to make it possible for Iris and Phoebe to meet, not in a physical sense – which was anyway impossible, practically – but through recording situations. I started by showing Iris documentary footage of Phoebe working with a non-speaking boy who has ASD, and later showed Phoebe my recording of Iris watching and responding to it. There’s a symmetry and a Russian doll effect in each woman watching the other, watching herself. Iris is watching Phoebe working with and interpreting someone who, as Iris said, has a similar relationship to verbal language to her own when she was a child. When I said that my work with Iris is ongoing, it’s this indirect mirroring between the women who inhabit such different yet overlapping modes of being and positions: that’s a seed I’d like to develop.

NH: There are at least two works I can think of, but maybe there’s more, about figures who have aphasia: The Whisper Heard (2003) with Tony O’Donnell and then I Hate (2007), with Edward Woodman. How did you encounter them or find out about them, and how then did you start an engagement with them individually?

-

Imogen Stidworthy, The Whisper Heard, 2003, installation, Matts Gallery, London. Parabolic focusing loudspeaker with the voice of Tony O’Donnell and synchronised video of his hands projected onto a satellite dish -

Imogen Stidworthy, The Whisper Heard, 2003, installation, Matts Gallery, London. Cubic monitors playing synchronised video sequence of Tony O’Donnell’s face (upper) and transcription of the artist reading aloud from Jules Vernes’ Journey to the Centre of the Earth

IS: I met Tony at CONNECT, the London-based charity for people with aphasia, after a long period of searching for a way to engage with aphasia in the context of speech therapy. And I met Edward through Tony indirectly, a friend of Tony’s and also after Judith Langley, Edward’s speech therapist, visited The Whisper Heard at Matt’s Gallery and got in touch with me via the visitors’ book. I’d met people with aphasia at the Speech and Language Therapy Department at Fazakerley Hospital in Liverpool, for example, but confidentiality issues made it more or less impossible to talk with them directly, let alone work with them. At CONNECT it’s a totally different situation, people with aphasia sit on the Board and decide their policies. Their approach to aphasia is not as a medical condition, but as a different life condition, and their aim is to help people to adapt and reconnect socially. They train volunteer conversation partners for people whose social lives and confidence have been dramatically affected by aphasia. That was the route I took which led me to meeting Tony.

Tony and Edward both lost the ability to speak at all initially, after the onset of aphasia. Losing language in that way is a totally different condition to so-called non-verbal autism – I say ‘so-called’, because it’s become clear that many people called ‘non-verbal’ have an intense relationship with verbal language, just not in linguistic terms, or not in ways that the people around them are aware of. Aphasia is localised damage to the brain through a stroke or an accident, and the effects are as varied and individual as there are people who have it. Memory and most other mental capacities are unaffected, but the language interface is, whether in terms of comprehension, or the ability to speak. This hugely affects your sense of self of course. As Tony said, ‘I’m the same person but I’m not the same person’.

Tony was so interested in what had happened to him that he was completely open to working with me in relation to his losing of verbal language. He had a huge vocabulary but was often left searching for a word for minutes at a time. Listening to that searching brings you to a cusp of understanding that you can almost, but never quite grasp, never quite pinpoint what’s being said. Over time this produced an incredibly strong sense of communication happening in the absence of verbal language – this was the basis for The Whisper Heard.

Running through all the works we’ve talked about there’s a questioning around different forms of sense-making, especially in relation to sense of self. Does it come more from something internal, or from what is reflected back to us by others; or does a sense of ‘self’ actually arise in the momentum of meeting with others, in the dynamics of relationship? What brings us to experience our own and other’s being differently? A state in which language has been shaken, in which you lose your capacity for thinking with it, or for choosing your words, or for speaking at all: these are conditions which resist the very terms in which such questions are being thought and engaged with.

NH: I Hate was made a few years later for Documenta 12 (2007). I know that Edward Woodman, the subject of the work, is somebody quite established as a photographer.

IS: Edward is known for his photographs of architecture and art, especially installations, during the 1980–90s. After his accident he had to stop working professionally, but when I met him in 2006, he was taking panoramic photos of the changing cityscape of the Eurostar development site around King’s Cross, close to where he lives, going to the same few viewpoints every week to record the changing forms and structures. The photos were fascinating to me, especially, in relation to ideas I was developing for I hate, and the relationship I saw between the building and collapsing of architectural structures and the construction of speech and language, and how each produces forms of social space and relationship.

NH: I Hate is also a very particular installation; it has a strong sensorial and audio-visual quality. You have the imagery of Edward doing his speech training, and his images of the construction site in King’s Cross. There is a wooden platform, scrolling text, and this architectural semi-circular wall structure with very directed sound coming out.

IS: The screens and walls were opaque or permeable in terms of sound as well as sight. The language of the installation drew on my approach for earlier installations that we’ve talked about, which evolved again, in the context of Balayer – A Map of Sweeping (2014 and 2018), with the different ideas and necessities for that work. And then Balayer and the actual map of sweeping,03 which appears in one of the videos, were direct sources for how we installed the exhibition ‘Dialogues with People’ (2018–19).04 For that we were working on a much bigger scale, which brought different problems and ideas again because it was an exhibition of ten installations, and all the different voices and structural forms were arranged in a single entirely open space.

Screens and walls structure the space and bring a rhythm to it, as do the elements for playing back sound and image, which all affect how a body moves through it. The immaterial elements – sound and light, visual image and the spaces between the physical elements – shape the sonic space, lines of sight and vantage points in relation to where you are, and how you move through the space.

The curved wall in I Hate resonates with sound and produces sound, which transmits through both sides. On one side it’s a rigid convex open-course construction, and then when you walk around into the inner curve of the wall, it’s acoustically insulated and the surface is taut and elastic, a containing space which wraps you in the voice. So, like the earlier piece we talked about, the wall sets up a distinct physical border in relation to the body, as well as a porous and enveloping relationship, in terms of sound and acoustics. So you’re on a cusp between material and immaterial qualities.

-

Imogen Stidworthy, I hate, 2007, installation, stills from three video sequences showing photographs by Edward Woodman on three industrial monitors, with motion sensor controlled playback. -

Imogen Stidworthy, I hate, 2007, installation, acoustically insulated sound wall playing composition of words of Edward Woodman, through focusing and monitor loudspeakers, Documenta 12, 2007

NH: Yes, there is this multi-sensorial aspect. In experiencing the work, you get the sense that it’s operating on different levels.

IS: You navigate it with the body and with the senses; you’re spoken to, interpolated, through different senses – one zone might be primarily sonic, another primarily retinal. These kinds of shifts between senses and registers were really key for how the space worked in ‘Die Lucky Bush’, the exhibition I made at M HKA in 2008.05 There they were generated between works by different artists, for example Teresa Margolles’ work Trepanaciones (Sonidos de la morgue) [Trepanations (Sounds of the morgue)] (2003), was next to Alfredo Jaar’s Real Pictures (1995). Trepanaciones is a sound piece on headphones, a recording of a skull being cut open, which she’d recorded in her day job in a morgue in Mexico City. Real Pictures is a set of sculptural arrangements of black archive boxes containing photographs he’d taken in Rwanda, witnessing the genocide and its aftermath. You can’t see the images, you can only read captions about them, printed on the lids. So, the cutting of the skull is an image that you don’t see, produced through sound, and while the sculptural stacks of boxes in Jaar’s make a visual image, the image of the work is being evoked in the mind, in the absence of the photographs. The relationship between them evoked another kind of cusp: between different orders of image, speaking to different registers of perception, sensory and otherwise.

The Whisper Heard and I Hate were the first multipart installations in which I conceived of the elements as each embodying a form of voice in themselves: partly sonic, acoustic, or literally spoken, and partly embodied in the elements as visual, material and structural forms of voice. They gave me the basis for a language to make ‘Die Lucky Bush’: working on the dynamics generated between the works in a landscape of different voices and different forms of voice. Producing distinct zones with no tangible borders.

-

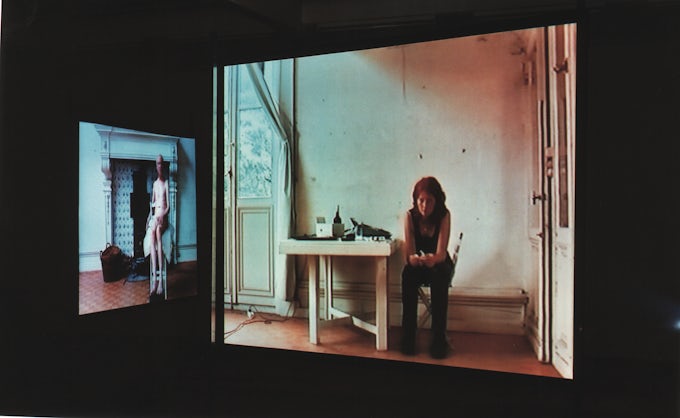

Imogen Stidworthy, Balayer –A Map of Sweeping, v. 2018, installation with Ambisonic soundtrack and three synchronised video sequences projected on acoustically transparent screens, 21min 30sec. Installation: ‘Dialogues with People’, 2018, solo exhibition,Würtemburgischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart -

Imogen Stidworthy, Balayer –A Map of Sweeping, v. 2018, installation with Ambisonic soundtrack and three synchronised video sequences projected on acoustically transparent screens, 21min 30sec. Installation: ‘Dialogues with People’, 2018, solo exhibition,Würtemburgischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart

NH: If I remember correctly, you told me that sometimes these connecting threads just appear when you’re working on one thing. I think it’s around the time when you were working on ‘Die Lucky Bush’, that you found out about Sacha van Loo, and that work is also a very multi-sensorial environment.

IS: On the train to Antwerp on my way to M HKA one day, somebody had left a copy of De Standaard on the seat, lying open on a page with a photograph showing Sacha at work. The article was about his incredible wiretapping skills, as somebody who has been blind since birth. In the photo you see him in his office with a target practice figure behind him, with a bullet hole in the bullseye. The photographic composition was all about creating an aura of power and knowledge predicated on the visual, while the article was about the power of his listening, of the aural, to glean information from voice and sound in forensic detail, especially in relation to identifying suspects. In the installation

I made with him there was a corresponding tension between vision and hearing; a fluidity of attention between sound and sight as well as moments

of sharp distinction.

How we engage our senses and how this shapes perception, was brought into a new paradigm for me by working with people who have ASD who have no practice of speaking at all. Thought and sense-making are happening through sensory perception far more than for verbal people. Spending hours at a time with the autistic adults in Monoblet, I started to follow the focus and movements of their attention, which took very different paths to my own.06 Inevitably this changed my perception of what was happening. One can’t know the experience of another person or see things as others do, but spending time with people over long duration, what you absorb can change how you perceive things – effectively, it changes how you perceive reality.

-

Imogen Stidworthy, Sacha , v. 2011; (.), 2012, multi-part installation of audio and video projections, acoustically insulated listening booth and cubic monitor, dimensions variable. -

Imogen Stidworthy, Sacha , v. 2011; (.), 2012, multi-part installation of audio and video projections, acoustically insulated listening booth and cubic monitor, dimensions variable.

NH: This relates to the question I had about your research process. There have been some interesting conversations about what ‘artistic research’ exactly is, compared to something more academic. In your work, your subject is primarily living people. I imagine that it involves years of research and development. So, I’d be interested in hearing more about that research process.

IS: Since I’m working with people a lot of my research is about spending time with them, being in dialogue, or in more or less staged encounters. It may take days or months to come to these moments, while doing all the things we do to deepen the engagement, to learn, to discover and develop different perspectives. Moments of production aren’t clearly separated from research. They fold into each other, and recordings from the earliest meetings often become part of the artwork, alongside recordings made later in explicit production stages. In the process things happen and are learned which affect me and the people I work with, to some degree; some aspects can be communicated verbally and some involve forms of learning and knowledge which can’t, but it’s all ‘research’.

When Iris [A Fragment] was shown at Bergen Assembly in 2019, Iris came to take part in a public conversation. She saw the full installation there, for the first time, and when she had watched it, she said something along the lines of: ‘It’s about an atmosphere that is full of information’. Information, as Iris explains, emerges in the ‘communication fields’ around and between people. It’s felt vividly and precisely as a kind of knowing which can’t be represented or transmitted any other way. Her comment changed my perspective on things that I’d always felt were somehow in conflict. When I was in art school, ‘atmosphere’ meant ‘vague’, it had no credibility whatsoever – ‘we don’t want “atmosphere”, we want rigorous conceptual thinking’. Our vocabularies change all the time and atmosphere does now have a place, I think. An atmosphere full of information, yet in a mode that produces no definable knowledge – no mappable, textual, explainable ideas: Iris’ comment really helped me make new sense of what ‘artistic research’ could mean. It has always slightly bemused me, especially in context of my own work, with the expectations it raises for certain kinds of knowledge to be evident in the work. Although in my process I study, learn and gather a lot of information along the way, that kind of transferable information isn’t present directly in the artwork – it’s just a part of what makes it possible. A lot of the challenge for me in developing a work is actually to emerge from that level of information almost entirely.

-

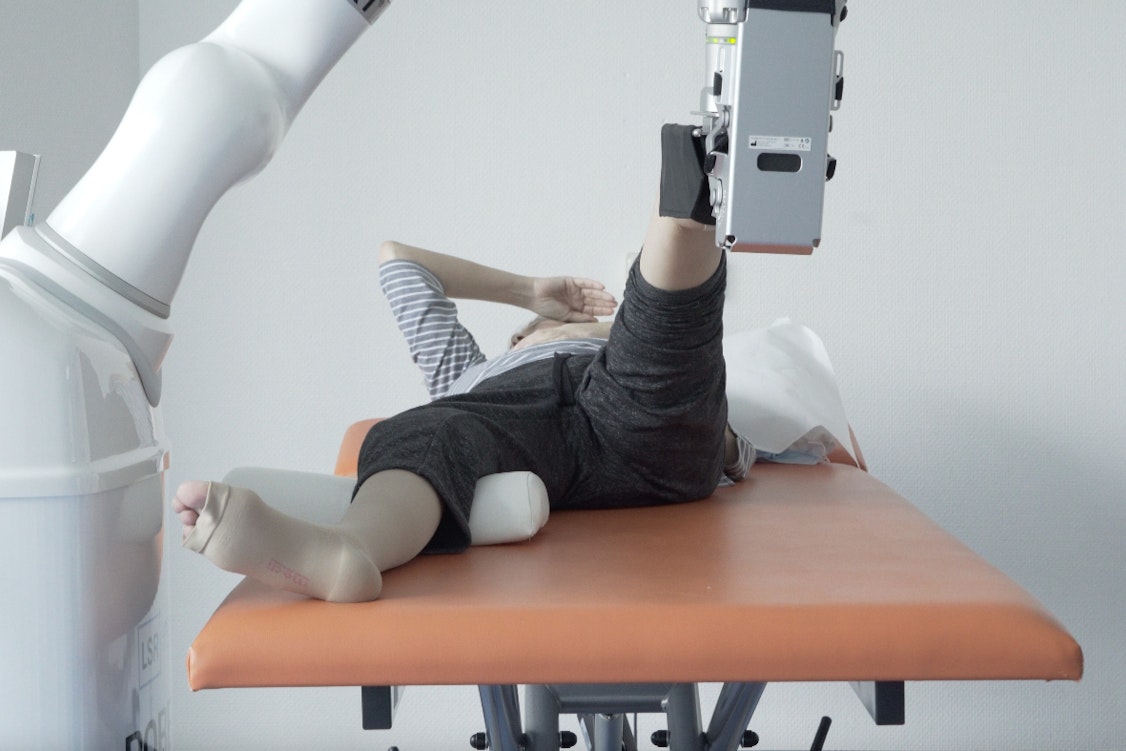

Imogen Stidworth, Notes, Lippoldsberg Rehabilitation Clinic for Heart and Stroke Patients, Summer 2021. Frau N during a leg rehabilitation session with robot ‘Robert’ -

Imogen Stidworth, Notes, Lippoldsberg Rehabilitation Clinic for Heart and Stroke Patients, Summer 2021. Ruined formaldehyde reservoir in the grounds of Lippoldsberg Rehabilitation Clinic, part of the original Paraxol explosives factory built in 1940, which was converted into a tuberculosis hospital in the 1950’s and later into the rehabilitation clinic. -

Imogen Stidworthy, Notes, Sörby, Sweden, December 2022. Iris Johansson during a Primary Thinking Work group session

NH: This is a slightly tricky question to articulate, considering other forms of language, and perhaps sense-making. Let’s say that you were to make work about speaking in tongues and forms of speech that are not based on linguistic structures, that supposedly come from, for example, a religious or transcendental space. I assume this would then take your practice in a tangential direction?

IS: I did actually work with two shamans in Korea, who channel the voices of gods who speak through them to their clients (Speaking in the Voices of Different Gods, 2012). It was a cultural context of which I had complete ignorance, but this aspect of their shamanic tradition is something I felt I could connect with through practices familiar to me in my own cultural context. I’d made several works which involved a disconnect between the voice and the body, with a ventriloquist, for example, and professional impersonators. They opened up other ways of thinking about self-hood and the idea of an authentic self. Uncanny relationships between the voice and the body also expose something about what underpins our feeling that communication with another person is happening, that we are connecting.

NH: There seems to be a difference between that piece and your other works. I’m really interested in the work of Susan Hiller and the way she dealt with paranormal phenomena. I don’t think she was looking at these things as being real, instead she was trying to learn something about the human condition. I get the sense that your work is also about the human condition and its ambiguity. In The Ethics of Ambiguity (1948), Simone de Beauvoir talked about the need to consider ourselves detached from things like religiosity or ideology, and that we should understand ourselves as being somehow unresolved, or ambiguous. And once acknowledged, this can serve as a starting point for emancipation. I do think that with some of the work that you’re making, there is some kind of emancipatory aspect that speaks to the fundamentally unresolved nature of existence.

IS: Hmm. Perhaps I would understand ambiguity then as a withholding or suspending of settling, on the level of sense-making. Ambiguity relates to not framing people and things in ways which might seem useful, but are more often destructive. It opens space for possibilities for co-existing differently, and for differences to co-exist. I really connect with what you said about Simone de Beauvoir. How do you make a work with a group of people who have ASD, a work which is about engaging with non-verbal modes of being, in such a way that autism does not become the subject? By the same token, the installation Sacha is not about blindness: how could I film him in such a way that the image is not of a blind person, but of his listening? This relates to withholding or stepping out from the kinds of framing – socio-political, cultural, identitarian –which reduce the scope of relationship. Mladen Dolar wrote about the voices in a conversation: voices are issued from one or the other, but belong to neither. That’s pretty much what I could hear when I was working with Edward Woodman. He spoke slowly, putting a lot of effort into forming and re-forming his word sounds, and Judith Langley spoke with her highly enunciated, received pronunciation, but she had to slow down and repeat words and sounds for Edward. Both of their voices would so noticeably change when they were together. Each would be coming towards the other, and both would be changed in the process.

Footnotes

-

Luce lrigaray, ‘And the One Doesn’t Stir without the Other’ (trans. Helene Vivienne Wenzel), Signs, vol.7, no. 1, Autumn 1981, p.60.

-

Sacha is an installation derived from elements related to the larger installation (.), which figures Belgian wiretap analyst Sacha van Loo, commissioned for the solo exhibition (.), Matts Gallery, London, 25 May–17 July 2011.

-

Gisèle Durand, Graniers 1975. Balayer la cuisine [Hand-drawn map of the movements of Jan-Mari and an adult sweeping the kitchen], 1975, Sandra Alvarez de Toledo (ed.), Cartes et lignes d’erre. Traces du réseau de Fernand Deligny, Paris, L’Arachnéen, 2013, p.232.

-

‘Dialogues with People’, solo exhibition at Würtemburgischer Kunstverrein, Stuttgart (DE) 2018–19, and NETWERK Aalst (BE) 2019.

-

‘Die Lucky Bush’, M HKA, Antwerp (BE). Group exhibition curated by Imogen Stidworthy, 23 May–17 August 2008.

-

This was during the process of developing Balayer – A Map of Sweeping (2014 and 2018), which involved a community of adults with ASD. The work figured Gilou Toche, Christoph Berton and Malika Boulainseur, and the couple who care for them, Gisèle Durand and Jacques Lin. Originally this was in the context of an experimental living space in which autistic children and neurotypical adults lived together in Monoblet, France, from 1967–86, developed by French educator, writer and film-maker Fernand Deligny.