Ruth Ewan’s Back to the Fields (2015/16) is an inventory of 360 objects listed in a Revolutionary calendar. Amongst the objects are a pickaxe, a plough and a small potted yew tree. Organised by months ranging from Vendémiaire (September/October) to Fructidor (August/September), it is an encyclopaedia of earthy smells and an array of colours and textures. Each singular item is numbered: we might recognise a cabbage, a ladder or a stem of budding cotton. Others are slightly less familiar: a harvesting basket, gypsum or the feathery leaves of the almost-forgotten vegetable skirret. The atmosphere is still, with the calm of a walled garden.

Each numbered object stands for a day in a calendar that was developed by a committee of politicians, mathematicians, poets and astronomers in the wake of the 1789 French Revolution. Presenting a rupture with the Gregorian calendar, which we still use, it was adopted throughout France for just over twelve years, from 1793 until 1805, and only briefly revived in Paris during the Commune of 1871.01 Today it seems abstract and distant, but Ewan’s installation is direct and unequivocal, with an insistent materialism. It is the fulfilment of a list of words, every item on the list present in some form here. There are no metaphors or abstractions of the things in front of us, with the exception of a few metonymical stand-ins: a horn for a cow or a salmon-fly for the fish itself. It is an exhibition of presentation rather than representation, but in gathering these objects together they accumulatively represent something else: an alternative, a prism, a different lens, through which to look at our annual cycle.

Currently exhibited in Live Uncertainty – the 32 02Bienal de São Paulo (10 September–11 December 2016), Back to the Fields was originally commissioned by Camden Arts Centre, London in 2015. The following conversation between Ewan and Chris Fite-Wassilak considers the work through ten selected items, chosen as a way to understand its structure, to highlight some of its unique properties and to see how it reflects on how we understand time today.

Ruth Ewan: The idea of introducing a secular framework of time is something that is almost inconceivable to us, with the long-standing familiarity of the Gregorian system. There are however elements of the calendar we are moving towards and many of the ideas within it have resurfaced over the last decades: seasonality of produce or knowing where foods and plants have come from. Interestingly, the only example I have come across of the calendar being of practical use was in a food market where they use it to teach the cycle of agriculture. In many ways, in Europe we already live out this calendar, we eat and smell it. If you observe nature, even within a concrete city such as London, you can locate where you are in the year. I find it very satisfying when I check to see what the Republican date would be, and you almost always find an obvious answer. I looked on the 28th of March and it was Daffodil. Of course!

Chris Fite-Wassilak: But the Revolutionary calendar remains a quiet and relatively unknown historical footnote. I first learned of the calendar indirectly. In Gyatri Spivak’s essay ‘Can The Subaltern Speak?’ (1988),03she looks to an oft-cited work from Karl Marx: The 18th Brumaire of Napoleon Bonaparte(1852), which took its title from the date in the Revolutionary calendar when Napoleon established himself as emperor. Writing about the allotment farmers that made up the vast stretch of France’s countryside, Marx stated: ‘They cannot represent themselves, they must be represented.’ It seemed a relevant comment for your exhibition, given the ideals and tensions of the calendar itself.

The months would be given new names following their intrinsic qualities: rain, snow, fog or flower (Pluviôse, Nivôse, Brumaire, Floréal).

RE: The Revolutionaries agreed that they needed to begin with a new framework, erasing the symbols of the church, the holy festivals, the saints’ days, and the previous ritualistic and habitual ways of life that came with it. First it was considered that the year would reflect historical events, therefore echoing the Revolution itself – the storming of the Bastille, for example, on the 14th of July. The weeks and months would change so that a week becomes ten days (as an intentional clash with the holy day) and months become thirty days made of three weeks, similar in basic framework to how the Ancient Egyptian Calendar was structured. The twelve-month structure was maintained, meaning there were twelve months of thirty days, plus an additional five or six festival days at the end of each year. The poet, dramatist and ‘mythomaniac’ Fabre d’Églantine then came up with the alternative naming system when it was agreed that rather than referencing the year of the Revolution annually, time itself would be given a blank slate to work from, beginning with year one. The months would be given new names following their intrinsic qualities: rain, snow, fog or flower (Pluviôse, Nivôse, Brumaire, Floréal). The Catholic saints’ days were substituted with the names we see in Back to the Fields, the majority of which are plants and trees. The fifth day of the week was named after an animal with, somewhat ironically, the tenth day of rest named after an agricultural tool or object. This created what calendar historian Sanja Perovic describes as a neutrally trans-historic set of rational and poetic reference points.04

Potato (11 Vendémiaire/Grape Harvest – 2 October)

RE: In recent years, nutritionally, the potato has had a bad press. But in eighteenth-century France it was a new thing, an exciting thing. The calendar was used as a way of introducing these new discoveries of the day. They were actively promoted by agronomist Antoine-Augustin Parmentier, who organised potato-themed dinner parties with the likes of Benjamin Franklin and the chemist Antoine Lavoisier. Before the Revolution, King Louis XVI had potatoes planted in his gardens and Marie Antoinette wore potato flowers in her hair in an attempt to make them appealing to the masses. La Cuisinière Républicaine was published in 1794, a potato cookbook, promoting potatoes in all forms as a food for the common people.

CFW: So, regardless of the Revolutionary ideals, the calendar was also simply a distribution method for information. Were some inclusions similarly aspirational, educational or even promotional?

RE: The calendar was very much engaged with the scientific thinking of the day. Elements that had recently been classified were included in the month Nivôse – sulphur, for example, or the much sought-after compound saltpetre.

Saltpetre (9 Nivôse/Snow – 29 December)

RE: In 1794 the Jacobins gave an address on the subject of saltpetre where they referred to it as the ‘the soul of muskets and cannons’, asking citizens to gather up ‘every last atom of this precious material’.05

Saltpetre (potassium nitrate) was found naturally forming on the stone walls of wine cellars, and a whole movement formed to gather it up and store it for use in making gunpowder. It’s now used as a food preservative, although popular rumour suggests the US military add it into soldiers’ food because it has another practical use, as an ‘anti-aphrodisiac’.

Winnowing Fan (20 Nivôse/Snow – 9 January)

RE: The first time I made the installation, a winnowing fan was one of the most difficult items to track down. The winnowing fan is a large shallow basket used to literally sort the wheat from the chaff. Because wicker baskets are susceptible to woodworm and rot, very few old baskets have survived, and there are even fewer people who have the basketry skills to make these now. None of the museums that had European winnowing fans were prepared to lend them because museum conditions could not be met with all the animals, plants, fungus, moisture and objects being placed on the floor. I contacted several basket experts. One pointed me in the direction of agricultural historian Dr. Maurice Bichard, who has written a fascinating book on the social history of baskets in Europe and has a large personal collection of baskets, one of which he kindly agreed to lend for the exhibition of Back to the Fields at Camden Arts Centre in early 2015. When the installation was created for the second time in São Paulo, it was easy to find a winnowing basket, as they are more commonly found in Brazil.

Woad (26 Pluviôse/Rain – 14 February)

RE: Woad, Isatis tinctoria, is a plant of the mustard family once cultivated for its blue dye. The plant reaches around 90cm, producing small yellow flowers followed by clusters of dangling, winged, oval, single-seeded fruits. The ground and dried leaves, when soaked and fermented, produce the pigment indigotin. Woad has been cultivated across Europe since Neolithic times. It produces a less concentrated blue than the ‘true’ indigo plant, Indigofera tincoria, which during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was banned across France and Germany – branded the ‘Devil’s dye’ and a ‘pernicious Indian drug’ due to the misconception that it caused wool to rot. A curator at the Automat Museum in Karlsruhe told me that centuries ago German woad pickers would gather their woad pickings at the end of the week and urinate on them to ferment and extract the woad dye. Meanwhile, the workers would drink beer in the pub all weekend (where some of the first music box automats were invented to keep them entertained). The blue colour would finally appear after Sunday – hence the term ‘blue Monday’. Its properties are now being investigated for use in the treatment of breast cancer.

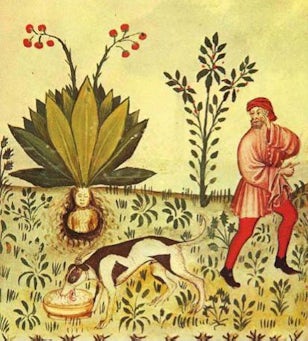

Mandrake (21 Ventôse/Wind – 11 March)

RE: The mandrake root is also really hard to get hold of, but eventually I found a mandrake enthusiast cultivating roots in Dorset. The roots are known for their narcotic properties – historically they were taken as a hallucinogenic drug. This is why old illustrations often show the roots as people, and there’s a myth that when you pull a mandrake out of the ground you hear it scream. Fearing that they would go to hell for pulling up a mandrake, farmers or foragers would tie the plant to an animal so that the animal would pull it up instead, as illustrated in the medieval handbook on health, the Tacuinum Sanitatis (c.1400). Mandrake was one of the plants we couldn’t find in São Paulo, and as it’s not permitted to import plant material or seeds into Brazil, several cuttings were encapsulated and displayed inside blocks of resin.

Pig (5 Frimaire/Frost – 25 November)

RE: In São Paulo ‘pig’ was represented by a large pig bone. In the previous installation at Camden Arts Centre it was represented by what’s called a Mexican hat pig trough, an iron trough lent to us by an antiques dealer. A local city farm also agreed to bring their mobile unit of live animals to the gallery garden, and the first animal to arrive was this huge, stinky, bristly, super fat pig that just waddled and grunted its way through the gallery bookshop. We’d tried to frame each day and each animal by providing facts, but in reality the animals themselves were so much more engaging than anything you could ever say or show to represent them, and the kids just wanted to touch them.

CFW: Do you think that tells us anything about the reasons why the calendar didn’t take? This distance between the ideal – an object presented as what should be thought about that day – and the reality of how people live their lives?

RE: That’s exactly why I wanted to make the calendar as a physical thing. You see it on paper and the words have limited understanding, though it has this poetic form that I think is quite beautiful. But then, to actually understand the words through objects it gives you this historic connection, this physical connection you wouldn’t get otherwise. We value objects in lots of different ways; for example, it wasn’t until I saw all the metals listed that I realised the importance of what’s not included. There’s no silver or gold, for example, but there is copper. Through having those things installed in a space you understand it in a different way. In Camden, at first it was this brown installation, and I was wondering why we were installing in January when everything was so bleak and dry, and then it all just came to life. It animated itself. Once the cherry blossoms came out all the other plants started to bloom and it felt like a clock hand was sweeping the room, with everything in its natural sequence.

Crayfish (25 Fructidor/Fruit – 11 September)

RE: Aside from the farm animals, there were a few living creatures we could exhibit safely and fairly. The crayfish were technically not the crayfish that you would have to hand in eighteenth-century France. They were American crayfish, the signal crayfish that were brought to Europe in the 1960s to supplement stock affected by a crayfish plague. They’re now categorised as an invasive species and considered a pest in the UK, so there were no restrictions on having them live in the galleries at Camden. Crayfish Bob, as he’s known, is an artist-cum crayfish pest controller in London who sets up traps catching American crayfish from the Thames and actively encourages eating them. He also supplies crayfish to the London Zoo for the otters. When he brought some to the gallery, we had to figure out how best to keep them.

Scurvy Grass (23 Ventôse/Wind – 13 March)

Once you know the Latin name for a plant, the Royal Horticultural Society can often identify garden centres that grow it. However, a lot of the plants on the calendar are non-commercial plants, wildflowers or weeds, and, as such, sixty or so proved really hard to find – with some they were out of season, and some were frozen into the ground, in which case we could try and get seeds. Scurvy grass was one of those; it grows only in salty environments, often found on coastal cliff tops. My mum, sister and dad live by the sea in Scotland, so I gave them a list of plants to forage and they were able to find scurvy grass and teasle. It’s actually a really beautiful plant. The leaves are full of vitamin C so it was historically taken on board sailing ships.

-

Ruth Ewan, Back to the Fields, Camden Arts Centre, 2015. Photograph: Marcus Leith, courtesy the artist and Camden Arts Centre -

Ruth Ewan, Back to the Fields, Camden Arts Centre, 2015. Photograph: Hydar Dewachi, courtesy the artist and Camden Arts Centre -

Ruth Ewan, Back to the Fields, Camden Arts Centre, 2015. Photograph: Hydar Dewachi, courtesy the artist and Camden Arts Centre

CFW: Is there a reason why so many of the plants on the list are now considered weeds?

RE: I think it’s due to the way we aestheticize certain plants, and then when other plants spread easily and come to be considered invasive they become weeds. I read something recently which criticised how we as a culture treat plants as wallpaper, as pretty back drops to our lives, rather than acknowledging how they feed us, clothe us and provide us with medicine. There is a theory that we are becoming ‘plant blind’. When I was installing Back to the Fields at the Bienal de São Paulo, all around Ibirapuera Park at the weekends there were long traffic jams. I walked through the park and I was surrounded by dense crowds – hundreds of people staring into their smart phones. I realised they were playing Pokémon Go. Isn’t this strange how we can identify hundreds of virtual Pokémon characters but we can’t identify most of these remarkable plants surrounding us?

Ash (29 Ventôse/Wind – 19 March)

RE: Although ash is one of the most common British trees, it is currently carefully controlled in the UK to prevent the spread of disease. At the Camden Arts Centre, we initially overlooked the fact that there were ash trees in the Centre’s garden, right under our noses. So, I went out and snapped a twig off of one and put it on the floor. It was one of the last things I put in position, along with the ‘topsoil’, which I grabbed a handful of from the front garden in the evening right before the show opened.

I’ve previously referenced an ash tree in a 2010 work, titled Liberty Tree (Stunted), which was part of the exhibition ‘Brank & Heckle’ at Dundee Contemporary Arts in 2011. It was an ill-fated ‘Tree of Liberty’ that had been planted in Dundee by the Friends of the People Society, an underground support group of the French Revolution. There’s a fantastic report in one of the newspapers from the time reporting the ‘crazed mob’ of Dundonians who danced ‘like demons’ around the newly planted common ash sapling yelling ‘Liberty! Equality! Fraternity!’ and decorating it with ‘ribbons, oranges, rolls and biscuits’.06

Conviction (4 Sansculottides/Free 20 September)

RE: Conviction is the fourth day of the Sansculottides, the six festival days that came at the end of the year in the run up to the Autumn equinox, with the others being Virtue, Talent, Labour, Honour and Revolution. The festival days (five in a common year with Revolution being the sixth in a leap year) brought the 360 named days of the year up to the 365 days of a solar year. Rather than naming the days after things, they were named after ideas. Conviction was named as the festival of opinion, freeing everyone to criticise the administration – which suggests the other 364 days of the year did not permit criticism! It is the idea that opinion is actively encouraged and particularly through creative forms, which is really interesting to me, through things like songs, sketches and caricatures. For the show at Camden Arts Centre, it was decided that those ideas shouldn’t be represented by things but through events. So there was a day where we compressed the festival days into a series of talks and performances. The only equivalent in our current calendar is May Day, the only non-religious holiday, the only day that remains from pre-Christian calendars.

CFW: That compression, though, is interesting – the negotiations and compromises of exhibiting the work and manifesting the calendar suggest an almost subconscious resistance to what it represented, or an indication of our distance now from what it represented. In realising the work in these different locations, have you found any conflict between institutional time and the Revolutionary sense of time?

RE: There is certainly a conflict in trying to show the calendar items simultaneously. The temporality of the plants and tools is what’s most interesting to me about the calendar, but in order to show these things collectively, I feel as though I am betraying the true nature of it. There is also certainly a conflict I’ve come to realise through working with plants and going between art and plant people. Artists and producers are so used to making physical demands and having those met, and the institution is such a controlled aesthetic space. We carefully select certain monitors, speakers, paint colours – we control everything so incredibly tightly. Working with live plants you can’t do that. You often can’t find the one you need and even once you find it, it may not like the surroundings.

Footnotes

-

Ewan notes that according to Walter Benjamin ‘clocks were also shot at during the commune but this may be a myth’. The 1967 Herbert Marcuse lecture ‘Liberation from the Affluent Society’ quotes Benjamin: ‘In all corners of the city of Paris there were people shooting at the clocks on the towers of the churches, palaces and so on, thereby consciously or half consciously expressing the need that somehow time has to be arrested, and that a new time has to begin – a very strong emphasis on the quantitative difference and on the totality of the rupture between the new society and the old.’ Marcuse’s lecture can be found in David Cooper (ed.), The Dialectics of Liberation, CITY: Penguin, 1968, pp.175–192. A transcript of the lecture can be found at http://www.marcuse.org/herbert/pubs/60spubs/67dialecticlib/67LibFromAfflSociety.htm.

-

First given as a lecture in 1983, and published in Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg’s anthology Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture , Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1988.

-

First given as a lecture in 1983, and published in Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg’s anthology Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture , Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1988.

-

See Sanja Perovic, ‘The French Republican Calendar: Time, History and the Revolutionary Event’, in Journal for Eighteen-Century Studies, vol.35, no.1, 2012.

-

Quoted in William Smyth, Lectures in History on the French Revolution, London: William Pickering, 1848, p.148 (available at: http://booksnow1.scholarsportal.info/ebooks/oca1/31/lecturesonhistor03smytuoft/lecturesonhistor03smytuoft.pdf).

-

See ‘December 1909 – The Tree of Liberty in Dundee’, http://bygone.dundeecity.gov.uk/bygone-news/december-1909 (last accessed 22 November 2016).