Barbara Visser is perhaps best known for her photographic series that probe the degree to which the depiction of a situation can be manufactured. In The World Belongs to Early Risers (2002), for example, different shots of a man surrounded by a group of people on a beach are styled so that it is uncertain whether the scene portrays a fashion shoot or something tragic. In this recent conversation with Tanja Baudoin, Visser discusses past and recent works in relation to her context-driven approach, which spanning design, performance, collage and architecture, maintains a focus on roles that are unstable, objects that cannot be self-contained, and places where histories accumulate.

Tanja Baudoin: Your work has a strong link with the tradition of conceptual art, but it also makes me think about Cindy Sherman. There are parallel preoccupations, such as ‘framing’, ‘posing’ and ‘character’, for instance. Are there any particular artists you consider to be part of your ‘artistic family’?

Barbara Visser: I’m a funny case. I’ve always tried to escape from the art world. I never felt entirely comfortable, never completely wanted to be part of it. So I never had those examples of artists I wanted to be like. For my material I always look at, listen to, read what people outside the visual arts say and do: writers, film-makers, journalists… Although I must acknowledge that when I was a student of photography [at the Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam], I sensed I didn’t belong there either. No one was talking about the things that interested me, about subjectivity or the changing role of photography – the digital world was rapidly emerging, Photoshop had started to change the game. I then moved to the visual arts department where the attitude was much more open. So I don’t want to dismiss the art context all together. It is the right field for me, yet I’m always trying to escape from the island it also is.

As a young artist working with photography, the thought of Cindy Sherman did give me some courage, but at a certain moment you grow into your own vocabulary. It just so happens that a few months ago I bought a special issue of Die Welt, a German newspaper that each year on the day of the fall of the Berlin Wall publishes an issue in which an artist takes care of the images for the articles. Last year it was Sherman. To see artwork merge with the banal facts of the ‘real’ world on the pages of the newspaper really excited me. Here is an artist who has ‘made it’ in every possible way, but she also steps outside the art bubble and sends her work back into the world.

TB: I asked you about artistic relations because I think you often concern yourself with what a ‘frame of reference’ can be. For instance, in The World Belongs To Early Risers, originally presented on street advertisements in Nice, multiple possible realities seem to co-exist – something that makes me as a viewer more aware of how I read an image and what my preconceptions are. How do you approach the changing conditions your work is seen in?

BV: A lot of my works evolve over time, so at one point they have a certain form and five or ten years later they may be presented completely differently. A photo-series of deteriorated design furniture that I originally made for A Prior magazine (Detitled, 2000) reappeared some years later on billboards in São Paulo, and now I sometimes present them in carousels as free postcards for people to take home. This is the advantage of working with media that can be reproduced, the idea remains the same but you can adapt it to the setting.

This position is highly related to the conceptual nature of photography. To me form is very important, but material less so, I guess that is the reason I am so fond of literature and film. To be able to make such an impact without a tangible manifestation remains unbelievably beautiful.

TB: How do you find the balance between keeping the spirit of the work alive and not ‘manipulating’ it too much so that you lose it when you respond to new settings and moments?

BV: It’s a paradox that in order to keep the essence or spirit of a work alive, sometimes it is necessary to change its appearance. I believe artworks should be capable of that transformation. I’m not so sure that their changing appearance is a way to make them fit the times – it has more to do with the way they are read in a certain space and context. But time does have an effect on my choices, so it cannot be totally ruled out. Someone once asked me if I felt my work needed plastic surgery, over time. But I would argue that making my works static would be a form of embalming them, as if they were dead. People, their ideas and histories are not static – I guess that’s what I love and hate so much about photography.

TB: Does that mean your works are never finished?

BV: I think of them more as way-stations, they sometimes have a physical manifestation. They can be on hold at a certain moment, but never for all time… Currently I’m approaching my older works as building blocks that I can play with, props if you like. They are treated as pure materials that I can work with again, and sample.

TB: Can you tell me something more about this new working process and how it relates to your exhibition at Kunstraum in London?

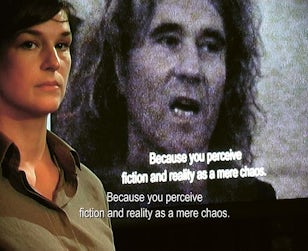

BV: I was invited to show some early works from the 1990s that have to do with the identity of the artist, or the artist as author. I chose to revisit four works from that period that together might add up to a kind of self-portrait. Looking at those works again now, I realise each of them contains a strong element of escapism. For example: I am asked to give a lecture, but I send an actress in my place, I later send a second actress to give a lecture as me to explain that work (Lecture on Lecture with Actress, 2004); or I secretly perform an action painting in a heavily masculine Pollock-like style on the gallery walls, unlike anything I would do at the time, but I end up covering everything with white paint before a visitor has seen it, and show only a photograph; or I propose to play an artist called Barbara Visser in a soap opera in a country I don’t know… Either I’m represented by someone else, or I’m physically not there, or I’m playing a role… There’s a constant friction between appearance and disappearance, a distance or a layer in between.

For some time I’ve been researching changes in the field of psychological aid from the 1950s onwards, and I’m particularly interested in the inability to really understand the workings of the brain. I’m fascinated by the idea that the subject of research, the psyche, is also the instrument used; we try to understand the brain by using the brain. There’s a fascinating and beautiful impossibility in that. I’m currently attempting to obtain my file from the Psychoanalytic Institute, to read what different therapists have written about me. I’d like to use the descriptions from this dossier in new work – not to reveal specific things about myself, but rather to use the descriptions as a form of fiction.

TB: This approach also demonstrates that the works are interwoven with each other and with the world, that they’re not autonomous things.

BV: For me, art is not chiefly about ‘things’, but about consciousness, critical thinking and dialogue. I need a form to express the idea but I then try to make things fluid again, so that the form never becomes too settled. I’ve recently come to realise, like many other artists, that film is an excellent medium for that, because it’s ephemeral, it’s an idea, it’s a story, it’s time. It’s where I find all of that comes together. I am using film as a form that can encompass older works, re-introducing them in the present moment, and at the same time reflect on the problematics of giving form, of representation and viewing – all those questions that pertain to artistic production and that I continue to explore.

‘Barbara Visser: Manual/2: The Patient Artist’ is on view at Kunstraum, London until 13 June 2015.