Chimurenga, in its own words, is a project-based mutable object: a print magazine, a publisher, a broadcaster, a workspace, a platform for editorial and curatorial activities and an online resource. Based in Cape Town, it operates through different media, from the pan-African print gazette Chronic and online broadcasts of the Pan African Space Station (PASS) to its ongoing function as a mobile site of education and research. From 8 October–21 December 2015, Ntone Edjabe, Chimurenga’s editor-in-chief, Graeme Arendse, art director and designer, and Ben Verghese, producer, presented ‘The Chimurenga Library’ at The Showroom, London on the invitation of Kodwo Eshun and Anjalika Sagar of The Otolith Collective and Emily Pethick of The Showroom. Avery Gordon asked Eshun and Pethick to talk about the making of the project, which is where this conversation begins.

Avery F. Gordon: How did the project start?

Emily Pethick: Our proposal was to bring the Chimurenga Library to London, but we didn’t realise until we got to Cape Town that there wasn’t actually a physical library.

Kodwo Eshun: When you visit the Chimurenga Library on the Chimurenga Magazine website, you see 32 scanned front covers of post-War independent periodicals sourced from Zimbabwe, South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Canada, the US, Burkina Faso, the UK, Egypt, Kenya, Morocco, France, India, the DRC, Jamaica and Senegal. Clicking on a cover takes you to a description of each magazine, its editorial network, a family tree of like-minded periodicals, more links and commissioned essays by poets, critics and novelists such as Akin Adesokan, Lesego Rampolokeng and Rustum Kozain. The Library is an online network that gathers the interrupted networks of Pan-African periodicals together. Some of these magazines, like South Africa’s Staffrider or Morocco’s Souffles, are celebrated. Others, like Zimbabwe’s Moto or Egypt’s Amkenah, are out of print and inaccessible.

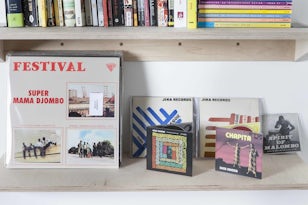

EP: We kept the title, but it became another form of library – an expanded idea of what a library could be. Chimurenga sent us a list of around two hundred objects to be sourced, which included books, records, films and other materials for the exhibition, about half of which they had themselves already. They proposed that we borrow everything from existing collections – we were not to ‘buy in’ any of the objects – so the process of seeking the rest became an intrinsic part of the exhibition process. Chimurenga built the exhibition plan around what we could find, so it was a flexible map, and people kept bringing things. The theorist George Shire brought more books. It didn’t assume a conventional form of an exhibition where everything is fixed and labelled and in boxes and vitrines. It was a more dynamic entity.

KE: The Library had to be built from available resources. We tapped into the local lending libraries in Edgware Road, university libraries, the personal libraries of friends and acquaintances. What you actually saw at The Showroom was six modest shelves supporting books and magazines that required a substantial effort to assemble.

AG: The library wasn’t something that pre-existed its making. It’s an interesting model for a public library because it differs so radically from the conventional state- or council-run public library that is public in name only. The public is a user, a part of producing the form and content of the library. I sent Robin D.G. Kelley a photograph with his passage about Fela Kuti on the floor of The Showroom. He replied by telling me he thought the Chimurenga Chronic was one of the greatest publications of radical insurgent thought, and that, because of his affinity with it, he had once envisioned creating a department of Black Studies modelled on the Chimurenga Chronic. Kodwo, I’d like to ask you to describe the affinities between Chimurenga and The Otolith Group practice.

KE: Perhaps the clearest way to indicate those affinities is to point to the publication of Chimurenga 12/13 in 2008, which was a double issue titled ‘Dr. Satan’s Echo Chamber’. It was named in honour of Louis Chude-Sokei’s magisterial essay on the Caribbean technopoetics of dub, which in turn was named after King Tubby’s remix of the song ‘Dr. Satan’s Echo Chamber’ by The Rupie Edwards Success All Stars. The double issue has two front covers, one for each magazine, and can be read from both directions. Issue 13’s front cover features an image from Icarus 13 [2008], Kiluanji Kia Henda’s photographic fictional series of a Pan-African state-sponsored space mission to the sun. Henda reimagined the Agostinho Neto Mausoleum in Luanda as the spaceship Icarus 13, built from a mix of steel and a covering of diamonds and powered by solar energy. I would argue that ‘Dr. Satan’s Echo Chamber’ single-handedly reoriented the project of Afrofuturism towards an expansive complexity that is capacious enough to embrace continental fictions such as the malevolent schematics of Abu Bakarr Mansaray, James Sey’s architectonic fabulations, Doreen Baingana’s demiurgic tales and Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s cinema of social horror. Chimurenga’s preoccupations resonate with Otolith’s ongoing concern with mutation and alienation. Both of us are drawn, asymptotically speaking, towards the syncretic synthesis of futures old and new. We operate between creation, criticism and curation. We are preoccupied by the will to complicate. We are interscalar vehicles that mobilise knowledges outside of the academy along vectors unbound by disciplinary protocols. We are informal socialities of study operating in the key of musics and the light of screens.

What is critical is that the Library did not aim to introduce South African literature to the London art world. What PASS did instead was to estrange Londoners’ ownership over the memory of the city by confronting them with memories of an exilic London that is cherished in Cape Town and unremembered in London. A London inhabited by jazz-avant-gardists such as drummer Louis Moholo, bassist Johnny Dyani, trumpeter Mongezi Feza, saxophonist Dudu Pukwana, pianist Chris McGregor and bassist Harry Miller, all of whom were forced into exile by Hendrik Verwoerd’s apartheid regime. Many of these artists can be seen, styled and posed in sets designed by photographer George Hallett for the front covers of novels by authors like Meja Mwangi and Williams Sassine that were published in Heinemann’s prestigious African Writers Series. Those covers now appear as scenes that document an expatriate community in a process of staging themselves. Another example of this process of defamiliarisation occurred when the artist Michael McMillan recalled his extraordinary experiences as an award-winning teenage playwright invited to participate in the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture [FESTAC] in Lagos in 1977. As McMillan evoked the spectacular opening ceremony of FESTAC ’77 at the National Stadium, listeners found themselves face to face with the provincialism of British media that was unable, then and now, to grasp the complexity of African cultural politics.

AG: I’d like to ask you to talk about what it means to use the term ‘Pan-African’, or ‘Pan-Africanism’, today. What does it mean to activate that term today? How do the London collaborators fit into a living pan-Africanism?

KE: Perhaps it’s useful to distinguish between the antagonistic and asymptotic trajectories of Pan-Africanism understood as a practice of statecraft and pan-Africanism as a practice of political aesthetics. The initial heroic Promethean phase could be located in the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester in October 1945, organised by the revolutionaries Kwame Nkrumah and George Padmore, who theorised the preconditions for the economic and military unification of the liberated continent in Towards Colonial Freedom: Africa in the Struggle against World Imperialism [1945] and Pan-Africanism or Communism? The Coming Struggle for Africa [1956].

That was followed by a period of official optimism in which the policy of continental unification was debated by delegates attending the All African People’s Conference in Accra, organised by Padmore and hosted by Nkrumah in December 1958. Those debates were codified by the Organisation of African Unity, founded in 1963 in Addis Ababa, whose legacy continues in the present in the shape of the African Union. A profound disenchantment with Pan-Africanism then takes hold amongst intellectuals in the 1970s and 1980s, as numerous one-party states adopt Pan-Africanist vocabularies in order to legitimate their authoritarian-populist policies of exclusionary Africanisation. The predatory Pan-Africanist policies practised by Zaire’s Mobutu Sese Seko, Kenya’s Daniel arap Moi and Cameroon’s Paul Biya – to name but three – inspire the critiques of Kwame Anthony Appiah’s In My Father’s House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture [1992] and Achille Mbembe’s influential African Modes of Self-Writing [2002], which target the discredited state ideologies of Pan-Africanism.

At the same time, the debates over the promises and the problematics of Pan-Africanism were enacted in and by the global cultural festivals staged on the continent throughout the 1960s and 1970s. From 2008, Ntone Edjabe, Stacy Hardy and Dominique Malaquais of Chimurenga embarked on extensive research into the cultural politics of those festivals that were inaugurated in April 1966 with the World Festival of Negro Arts [FESMAN] in Dakar, as conceived by Senegal’s Léopold Sédar Senghor. That was followed by the Pan-African Festival of Algiers, opened by Houari Boumedienne in July 1969. In October 1974, Mobutu Sese Seko welcomed audiences to attend the world heavyweight boxing championship between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, also known as the ‘Match of the Century’ or the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’, in Kinshasa. Finally, in 1977, Nigeria’s Lieutenant General Olusegun Obasanjo hosted FESTAC ’77 in Lagos and Kaduna. Taken together with the investigations of the Chimurenga Library, these two research projects indicate the intranational ambitions of Pan-Africanist political aesthetics from the perspective of the pan-African present. One way of characterising the practice of Chimurenga is to look at their methods for inventing investigative aesthetics, which are flexible enough to move within and between these scales so as to reveal the practices of aesthetic sociality that exceed and elude and complicate the state-sponsored spectacle of the global festival.

EP: I was thinking about how an exhibition can work not only to share what you know, but also to create space to find what you don’t know. Through ‘The Chimurenga Library’, or rather the sourcing of objects, things emerged that we hadn’t been looking for. There were the photographs by George Hallett that Christine Eyene offered, George Shire brought in unpublished Dambudzo Marechera manuscripts -– all sorts of things that started to broaden the picture. PASS became a live broadcasting programme of music, interviews and events with Chimurenga collaborators in London, which included musicians, writers, curators, film-makers, journalists, etc. We invited the sorryyoufeeluncomfortable collective to have a residency in conjunction with the project and to programme a slot of PASS, and they were a good conduit for bringing in and giving space to a younger generation. The radio broadcast was interesting for me because of the durational aspect of five days, and how the audience fluctuated in relation to this. The speakers were sitting with their backs to the audience. You don’t know who’s listening, but people did come to the space saying that they’d been listening all day. Or you’d see responses from remote listeners on Twitter. A project can resonate on many different levels and it’s important for us

to figure out how these things translate across different registers.

KE: The guests were continually narrating events and speculating on the implications of those recollections in ways that generated a continuous complexification of what pan-Africanist practices had been, could be and might be.

AG: The Chimurenga Library took place at the same time as a large exhibition and set of public programmes titled ‘No Colour Bar: Black British Art in Action 1960–1990’ [10 July 2015–24 January 2016], which, with a lot of work, trouble and Heritage Lottery Fund money, managed to get into London’s Guildhall Art Gallery. The show was anchored in the Black Arts Movement, with a reproduction of the Walter Rodney Bookshop designed by Michael McMillan in the centre. There were vitrines in which you could read moving letters between Eric and Jessica Huntley, and artworks hanging on the walls – a conventional form. I was struck by the difference between these two shows, which felt like two different and deeply disconnected worlds. Not only the exhibition venues – one next door to the Bank of England and the other in a North African and Middle Eastern working-class neighbourhood – but the different art and social worlds surrounding them. I think it unlikely that the people involved in ‘No Colour Bar’ came to The Showroom, and this speaks of a certain split politically, especially with the older generation who were involved in Pan-African and radical Black diasporic politics in an earlier era and still today. What do you think? Does it tell us something about what pan-Africanism and radical Black politics means, and doesn’t mean, in London today?

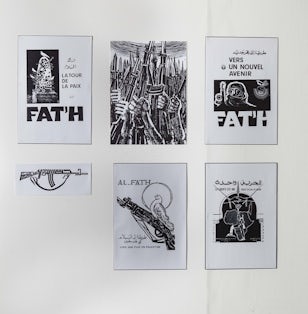

KE: There are generational, aesthetic and political distinctions between the works exhibited in ‘No Colour Bar’ and those in ‘The Chimurenga Library’. In the former, we can see artists that allied themselves with practices invented by the Caribbean Arts Movement and the Black Arts Movement. These influences converged in a diasporic Third World-ism epitomised by the epic gatherings around the International Book Fair of Radical Black and Third World Books, founded by activist-publishers John La Rose and Jessica Huntley in the early 1980s. ‘No Colour Bar’ narrated a transgenerational genealogy of post-War artistic politics practised by artists that actively participated in the contingent process of black British becoming. The works exhibited in ‘No Colour Bar’ speak of the political triumphs and defeats faced by generations that were all too aware of their position within a ‘colony’ whose existence emerged in reaction to state indifference and popular racism. Artists like Fowokan and Chila Kumari Burman envisioned the colony as a community whose cosmopolitanism could withstand the structural conditions of state-sanctioned subordination. The emboldened defiance of many of the works in ‘No Colour Bar’ speaks to and from the dynamics of this struggle; painting and sculpture plays a key role in this movement. ‘The Chimurenga Library’, by contrast, integrated murals of front covers, Palestinian Liberation Organization posters and videos by the Kongo Futurists into a network of quotations that form a cartography of thought.

EP: But also Chimurenga is not strictly ‘art’. They include art and use the exhibition as an expanded editorial approach that spatialises knowledge and draws the connections between things in ways that can’t be done in a two-dimensional format. There’s a whole series of cartographies that Chimurenga made in an issue of the Chronic earlier this year, which are all reproduced in pencil. Graeme Arendse, Chimurenga’s art director and designer, described how every time they thought they’d settled on a map someone would make a change and they would have to redraw the whole thing. He described how they hand-drew the maps through a desire not to present them as fixed entities – -an approach to representation that’s not about claiming an authority. In some ways the exhibition worked like this. It was a kind of sketch, mapping out different routes and drawing out strands of thinking without trying to claim authority. I have the feeling that Chimurenga invites its contributors, followers and audiences to think with them, rather than broadcasting as a one-way channel.

AG: For me, you touch on something very important that has to do with the tension between politics and culture. The generation of ‘No Colour Bar’ you’re talking about, Kodwo, to a large extent they thought about making art in the service of a political project, and the form that project took was community organising as minority communities. That’s very different than the case in South Africa, where it was about majority – not minority – organising. Your generation said we have a different notion of aesthetics, a different notion of cultural politics: we are not artists in the service of the revolution. In the past, people created community organisations to deal with police harassment and police killings, or to deal with Black children being IQ tested in schools, or to organise lawyers for prisoners and refugees; the people who created a bookstore where none existed. That is a different political culture than working as a politically engaged artist in the contemporary art world. I wish more people from the community-politics world had seen ‘The Chimurenga Library’, because it’s not only the undisciplined/disciplined process of how they work, but the capaciousness of the ideas, the taking of positions that are historically intimate and at the same time critical and sharp, and in the present moment are not obsequious to power, while always being reflective about the representational format and forms of communication. We need that politically, not just artistically.

KE: Chimurenga recognises the extent to which contemporary audiences find themselves isolated from the interrupted networks of previous aesthetico-political struggles. It continually invents formats for navigating between intergenerational histories. Using the floor as a space to unfold the pages of the periodical, it invites visitors to move within texts selected and organised according to specific trajectories. This citational aesthetic alludes to the ways in which people move from link to link. It suggests the work of building forms of articulation. The majority of people that visited The Showroom did not visit Guildhall Art Gallery and vice versa. Chimurenga’s navigational aesthetic draws attention to the gaps in knowledge that simultaneously function as channels between knowledges. Those arrows that point to quotations draw attention to the ways in which people process pan-Africanism now. The political aesthetics of pan-Africanism share space with and are mutated by discourses and styles of Afropolitanism, Afropessimism and Afrofuturism. People move between these vocabularies all the time without a map to orient them. ‘The Chimurenga Library’ invited you to navigate these worlds of thought, which are conceived as mutable spaces of sustained complexity.

EP: I think in relation to this sense of disconnection between what was happening at Guildhall and what was happening at The Showroom you could ask, what does the space of an exhibition lend? I do think it’s a site where you can bring things into contact. That, in a way, is part of the curatorial approach of Chimurenga, in thinking along these different trajectories or routes in relation to each other and finding ways to cross-read these different things in order to produce a more complex picture. And at the same time, the approach of the exhibition was about bridging between different communities, or people meeting and other relationships being forged through it.

KE: ‘The Chimurenga Library’ instituted itself as a time and a space in which people could meet. People planned future activities. It became a social space where pan-Africanist aesthetic politics were mutable and navigational. That is what people enjoyed about the space and that’s what people miss. The Library insisted on that missing space which still does not exist. It drew people’s attention to the implications of

that absence.